Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for July 2021 is Sustainability. We invite submissions on the diverse aspects of sustainability throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

In the face of looming environmental concerns, sustainability has garnered particularly massive attention recently. The term has percolated into several spheres, one of which is food and nutrition. With the discourse on nutrition and health being a dominant one, a significant number of people are choosing ‘health conscious’ living.

Consequently, certain diets and foods are preferred over others, creating a burgeoning demand for a few ‘coveted’ nutritional foods. Restaurants have now adapted to consumer demands and do not offer one standard menu, but a variety of menus including keto and vegan menus, to name a few. Additionally, health bloggers and influencers continue to shape the idea of health, nutrition and food consumption by consolidating the categories of healthy and unhealthy foods.

An additional layer of westernisation is visible in this domain, as the demand for ‘western food products’ and diets are prioritised, almost as a prerequisite to leading a sustainable life. Western practices continue to encroach this domain, as the demand for – quinoa, guacamole, cherry tomatoes and sourdough bread – to name a few, now form a part of the urban diet. Indigenous foods, and cooking practices, once erased by the West, continue to be bracketed out even by locals. Today, an ironic combination of sustainability and capitalist consumption can be found in our popular mainstream nutrition ideology.

Rajasthan: A thriving local model of slow food and zero waste

Bea Johsnon, the founder of the zero waste lifestyle movement and author of Zero Waste Home, proposed the idea in her book in 2013. Zero waste, as the name suggests, implies minimisation of waste through redesigning resources, and recycling them in an attempt to generate lesser amounts of waste. The concept can be applied to various domains, one of which is food production and consumption. For instance, Josh Niland, an Australian chef is well known for his ability to handle fish with utmost care, using every part of it to create dishes.

However, the idea of zero waste did not exclusively emerge in the west. It has been found in our indigenous practices handed down through generations. The only difference is that the practice in India did not have a formal coinage unlike the west. It was simply a sustainable practice that formed a part of the repository of generational knowledge.

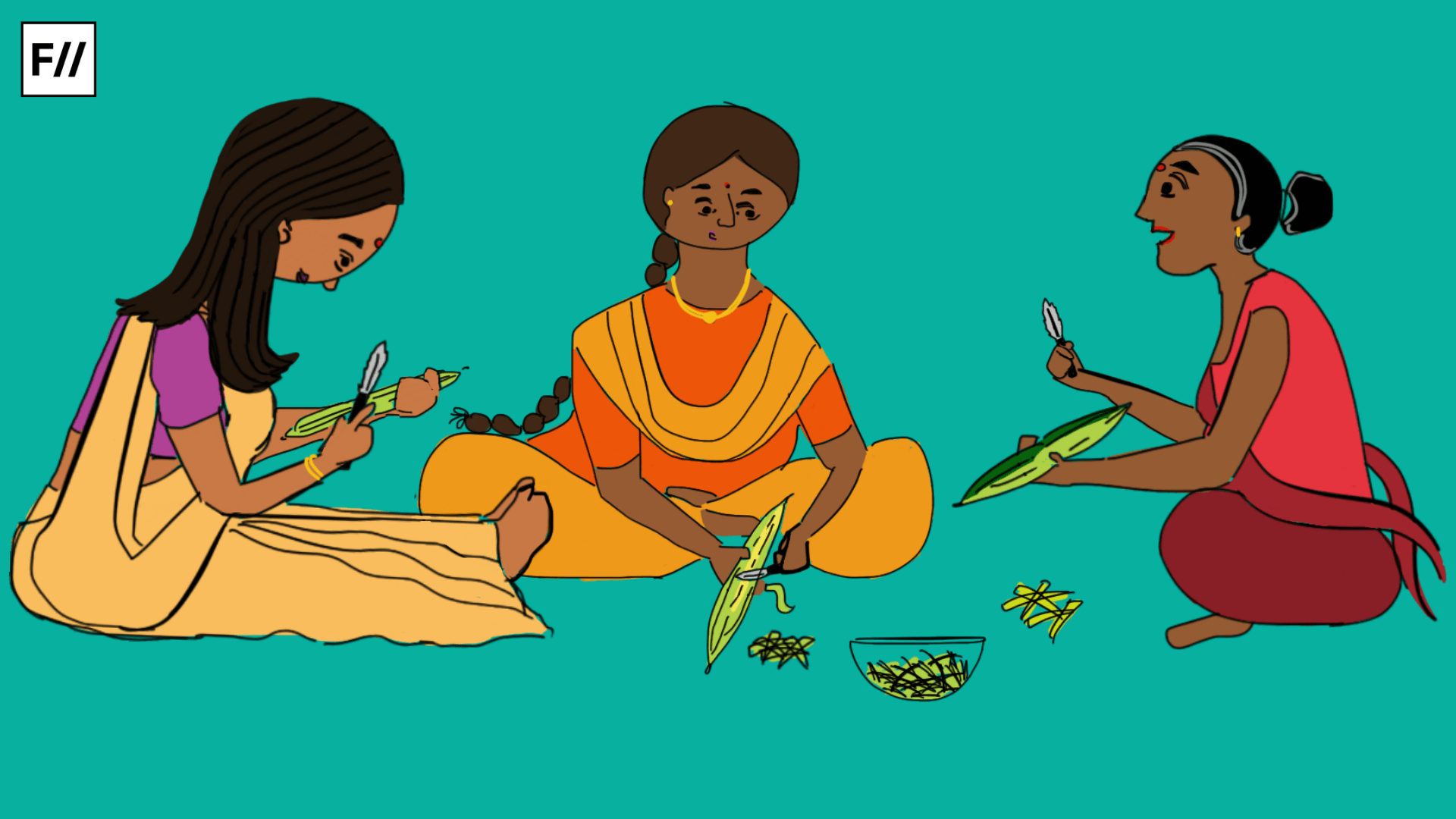

Rajasthan is home to the tradition of using peels, pits, seeds, and rinds of fruits and vegetables to make dishes. The pits and peels are utilised for their medicinal properties. Elders in Udaipur told People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI) that this practice has been handed down from generation to generation. Food itself was viewed as a luxury with no part meant for wastage. This led to innovations to maximise the use of a commodity. When no use could be squeezed out of the fruits and/or vegetables, they were used as animal feed or were composted in the fields. This process, almost interwoven with commonsensical knowledge in the region, has no name. It did not stem from the sudden urge to be ‘sustainable’ but was commonplace as curbing wastage was the motive.

Like zero waste, the slow food movement, though formally coined in the west, has been traditionally practiced in Rajasthan for many many years.this form of minimalism in terms of dietary practices, and clean eating is evident from the methods in which Rajasthani meals comprise the peels, the rinds, the seeds, and every part of a vegetable, most of which are promptly discarded as unclean and “polluting” in urban dietary parlance

With the growing debate on sustainability and the need to incorporate the same in one’s lifestyle patterns, many in Rajasthan are reclaiming this process, integrating it to the ‘zero waste food’ narrative.

Vijaylakshmi, one of the many who uses zero waste cooking, uses the vegetable and the peel to make two different dishes in the same meal. She told PARI, “I learned it from my mother, aunts and grandmothers. I was less interested in cooking when I was younger, but now I like experimenting with many kinds of foods. My family enjoys the taste of different subzis (vegetables). There are so many benefits to eating peels, from extra nutrients to fibre and iron.“

Founded by Carlo Pertini in Italy in 1968, slow food promotes local food and traditional cooking. The slow food movement emphasizes three principles: taste education, defense of biodiversity and interaction between food producers. The essence of the movements is in eating clean, and choosing simpler, healthier foods over mass produced, unhealthy fast foods.

Like zero waste, the slow food movement, though formally coined in the West, has been traditionally practiced in Rajasthan for many many years. The movement advocates the need for reliance on geographically specific foods that are locally produced in a sustainable manner. This form of minimalism in terms of dietary practices, and clean eating is evident from the methods in which Rajasthani meals comprise the peels, the rinds, the seeds, and every part of a vegetable, most of which are promptly discarded as unclean and ‘polluting’ in urban dietary parlance.

Vidhi Jain, conscious of zero waste and slow food movements in Udaipur, believes that most people in modern cooking barely use the full vegetable let alone its peel. “I was taught by my grandmother,” Vidhi says, “And by my husband’s grandmother or jia, who used to live with us. It would frustrate me when jia would sit for hours, peeling the skins from each individual pea. I felt she was wasting time, but she was very aware of the resources in the house.”

Also read: What Has The Feminist Movement Got To Do With Food?

Vidhi also elaborates on the healing purposes of certain peels. She peels a pomegranate, dries the peels in the sun and then boils them in water. This concoction is a remedy for stomach problems. “I enjoy learning and cooking our traditional foods. It’s important to keep this knowledge alive.“

The urban choice of premium food: Polarising diet on the basis of privilege

Food is not only viewed in the functional sense of cooking and eating, but also a symbol. Dietary habits and food products have different symbols attached to them.

The urban elite’s preference for quinoa, guacamole, sun-dried tomatoes and the like are reflective of the adherence to the “valuable” western way of practicing sustainability. This not only promotes a capitalist consumption pattern, but also polarises sustainable eating on the basis of access and privilege

The symbolism surrounding foods are socio-culturally dictated, and vary geographically and cross-culturally. Binary oppositions operate even in food. Distinct categories of edible-inedible, clean-unclean, raw-rotten and the like exist even in this realm. Clear cut bifurcations dominate the discourse of what is ‘acceptable’ food, and these yardsticks are socio-culturally and religiously determined. In keeping with this notion then, for many, using peels, pits and seeds, the frequently disposed and ‘unusable’ parts of a vegetable and/or fruit, is a radical idea rooted in reclaiming the once ‘unclean’ or ‘disposable’ parts. What makes the underlying politics of this acceptable to the mainstream dietary notions is the cultural process of cooking and transforming the raw, unsuitable ingredients and products into something worthy of consumption, and replete with flavour.

Another dimension of symbolism in terms of food is practicing diets that encompass items that have a particular social status attached to them. The urban elite’s preference for quinoa, guacamole, sun-dried tomatoes and the like are reflective of the adherence to the ‘valuable’ western way of practicing sustainability. These are not regular, easily accessible local foods. They are fancy and come with a certain sense of stature attached.

Internalising such ideas is just another way of subtly succumbing to westernisation. While for some the aim of being sustainable results in eating clean and consuming premium food products, for others the consumption of such products is tailed by the peripheral need to be sustainable. This not only promotes a capitalist consumption pattern, but also polarises sustainable eating on the basis of access and privilege.

Also read: We Need To Address The Issue Of Food Security In Residential Campuses

The commercialisation of quinoa for instance, caused a domestic shortfall of the same for local farmers and suppliers in Peru and Bolivia. The Global North-Global South discourse continues to operate in terms of food production and consumption. This form of colonisation begins with indigenous foods being recognised by western eyes, that are then quickly commercialised and exoticised, generating demand, and creating profit, but more importantly threatening local food systems and modes of living.

Are we really waiting for the west to recognize, for instance, the practice of eating the peels and seeds of vegetables? Or would we consume it only if it was offered at a restaurant that anglicised its name as “Bottle gourd crispy fried skins, chilli tomato sauce, garnished with sunflower seeds?” The western model of sustainability need not be applied to a country already rich in sustainable practices and nutritional foods. The lens with which we approach sustainability needs to shift. Jowar bajra are rich local substitutes for quinoa, but vernacular food practices are continually looked down upon in the quest for chasing a certain kind of elite sustainability.

Sustainability then, becomes just another capitalist idea, and not a lifestyle choice, as it embraces certain foods and practices, while devaluing others.

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Shaniya Karkada is a Postgraduate student of Sociology at Christ University. She believes in learning something new, no matter how small, everyday. She has many interests that constantly change, but the one that has remained is exploring Gender Studies.