To keep the social order and the shackles of morality intact, the spies of the night in the city of colonial Calcutta would venture out in the darkest hour amidst the ‘dangers’ of deviant women to save the respectable sections of the society. Who were they and how did they shape the social thought clandestinely?

When we attempt to analyse female sexual deviancy historically, often our thought leans towards women who are perceived as sexual excesses, ‘bold’, ‘flagrant’ and ‘abhorrent’ like sex workers. In the late 1800’s, the notion of sexual deviancy engulfed any women who were seen in public spaces outside the domestic. This represented a grave moral anxiety and was a point of commonality between native and Victorian moral codes. The control of ‘deviant’ women became a binding attribute between the coloniser and the colonist, ultimately shaping the notions of ‘deviancy’ and ‘deviant female behavior’.

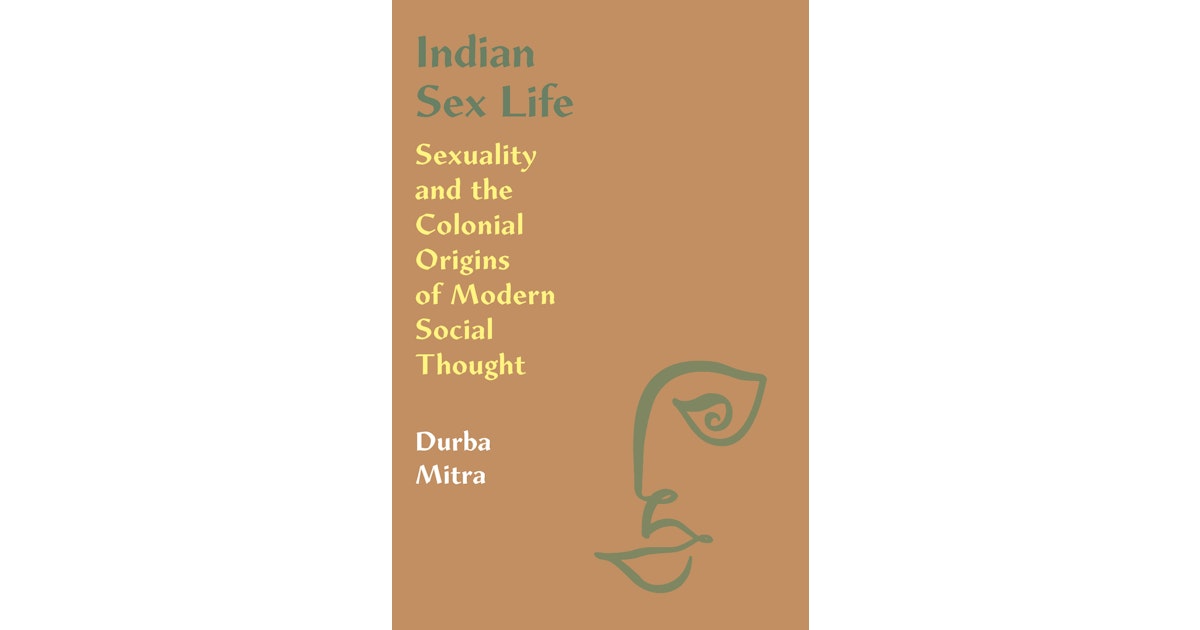

Controlling women’s sexual desires became a singular point anxiety that further developed and led to a kind of social cohesion between the ‘respectable’ sections of native society and the British colonial officials. Durba Mitra talks about this in her recent book titled, ‘Indian Sex Life: Sexuality and the Colonial Origins of Modern Social Thought’ and says that “the unification of diverse sexual practices through classifications of deviant female sex constituted the social as a discrete domain of inquiry”.

Controlling women’s sexual desires became a singular point anxiety that further developed and led to a kind of social cohesion between the ‘respectable’ sections of native society and the British colonial officials. Durba Mitra talks about this in her recent book titled, ‘Indian Sex Life: Sexuality and the Colonial Origins of Modern Social Thought’ and says that “the unification of diverse sexual practices through classifications of deviant female sex constituted the social as a discrete domain of inquiry”.

During the 1800s and 1900s, an array of books on sexuality and social development came in circulation in colonial Bengal. These were generally authored by the ‘respectable’ and educated Bengali men often belonging to upper caste backgrounds. One of the prominent examples is of Radhakamal Mukherjee, who is often regarded as the, ‘father of Indian Sociology’. Durba Mitra argues, how these books hinged their study of sociology and modern social thought on deviant female sexuality. The discussion and debate around deviancy fettered the colonial society at large.

Interestingly, in the city of Calcutta, a very peculiar and clandestine surveillance began to further alter the social thought regarding female sexual deviancy. This was not a British statist project, but a sociological project undertaken by reputed Bengali men to keep the social order and the shackles of morality intact. As a result, the night spies of Calcutta would venture out in the darkest hour amidst the ‘dangers’ of ‘deviant’ women to save the day.

Satirical sketches became an emerging form of social surveillance in the nineteenth century Calcutta. These books/manuals were generally published for ‘Calcutta lovers’ under the garb of providing an insight to the city life and mapping the backstage spaces of entertainment. However, these manuals clandestinely underlined detailed instructions to remove social evils and sexual excesses of nighttime Calcutta. Often written by ghostwriters under pseudonyms, they contained detailed descriptions of deviant women and the spaces that represented the ‘real’ dangers.

These books became an emerging form of social surveillance in the 1860s. Raater Kolkata (Nighttime Calcutta) and Hutom Pyachar Nyaksha (Sketches by a Watching Owl) are the two key texts that shaped the social thought of colonial Calcutta regarding ‘deviant’ women. Meant particularly for a male audience, these manuals were written by self-confessed spies of the night who would mark the pockets of deviancy to warn and instruct ‘respectable’ people to be aware of such women.

‘Raater Kolkata’ by Hemendra Kumar Roy, who acted under the pen name of Meghnad Gupta, was written in 1923. Roy would venture in the ‘shady’ streets of Calcutta during the night portraying a dark and grey visuals in his book much like the gothic imagery of Edgar Allen Poe. The first line of his book categorically highlights that ‘Calcutta Nights has been written exclusively for an adult male audience’.

This book was not just about sex workers or whom the society is known to associate sexual deviancy with. It categorically mapped all women who ventured out during the night to enjoy a play or probably would converse freely with men in clubs. Roy himself says that these women of ‘loose morals’ came from socially ‘respectable’ households, but they rather chose to go to public places during the night to prowl on men.

Raater Kolkata is a narrow and raw description as compared to another book called ‘Hutom Pyachar Nyaksha’ written in the year 1862. Hutom was written by an upper-caste affluent zamindar in Bengal, Kaliprasanna Sinha. It is written in eloquent yet satirical, ‘sadhu bhasha’ the sanskritised version of Bengali often used by priestly-classes as compared to ‘cholito-bhasha’, the colloquial way of writing or speaking. (This is a classic example of Bakhtinian diglossia.) While Hutom is a rich cultural source for sociological analysis of colonial Calcutta, it simultaneously paints a picture of city’s sexual ‘excesses’ that comprises of mapping sexually ‘deviant’ women.

One of the ideal examples in Hutom Pyachar Nyaksha is the detailed descriptions of nautch-girls or ‘khemtawallis’. Irony interceded the narrative when Sinha goes to the extent of describing the physical attributes of these dancers in of course priestly Bengali language (‘sadhu bhasha’);

“Some babus even strip the khemtawallis before the dance begins! In some places the khemtawallis aren’t given tips till they kiss! You can’t mention these things aloud anywhere… The khemta nautch began. The khemtawallis sang a saucy song from behind, while two middle-aged khemtawallis danced rhythmically, swaying their hips to the song.”

Stories of debauchery of the Bengali babus to the flagrancy of European women to the elaborate discussions on brothels and Calcutta playhouses are what these books comprised of. These two key texts represent a sexual mapping of the city of Calcutta that categorises women, spatially and characteristically. Raater Kolkata (Night-time Calcutta) and Hutom Pyachar Nyaksha (Sketches by a Watching Owl) clandestinely shaped the social thought of colonial Calcutta regarding ‘deviant’ women. In the façade of making the upper classes aware of who were popularly seen as fallen women, it systematically altered the modern social thought regarding any woman who ventured out in public without a father, brother or a husband. It reinstated the domesticity that most of the ‘respectable’ women embodied during this time. These texts pushed women who were trying to make a space in the public like the actresses and dancers to the periphery where such professions were seen from a perspective of disdain.

Raater Kolkata (Night-time Calcutta) and Hutom Pyachar Nyaksha (Sketches by a Watching Owl) clandestinely shaped the social thought of colonial Calcutta regarding ‘deviant’ women. In the façade of making the upper classes aware of who were popularly seen as fallen women, it systematically altered the modern social thought regarding any woman who ventured out in public without a father, brother or a husband.

The texts secretly shaped the social thought of their audience and simultaneously provided a source of entertainment. This also highlights the dichotomy steeped in these texts. “Calcutta Nights has been written particularly for a male audience..” Why? This pattern was clearly reflective of a process of social surveillance of vulnerable female bodies in colonial Calcutta. Written by self-confessed spies of the night who are no more than an embodiment of male gaze; these spies would map the pockets of deviancy and closely observe women and their physical attributes to warn ‘respectable’ people to be aware of such places and moreover such women.

References

Durba Mitra, Indian Sex Life: Sexuality and Colonial Origins of Modern Social Thought. Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 2021;28(2):324-329.

Twisha Singh is a fourth year PhD research scholar at the Department of History and Classical Studies, McGill University, Montreal, Canada. Her research area includes Modern British History, South Asian History, Theatre and Performance Studies, Gender and Sexuality Studies and her theoretical approaches include feminist and post-colonial literary theories. She is a Graduate Member of the Canadian Historical Association. She is also an editor of a peer-reviewed journal of South-Asian studies called HARF at her University and the design-editor of her department’s official journal called CHRONOS. Her research has been recently awarded the prestigious Wolfe Graduate Fellowship 2021. Previously her project has been awarded the Graduate Excellence Award consecutively for two years 2018 and 2019 by the Department of History and Classical Studies, McGill University. She has previously presented papers at Christopher Newport University, Dublin City University, Lund’s University, University of Edinburgh, Lomonosov State University and Jawaharlal Nehru University. She has been a part of a multi-university project on, “Modalities of Cultural Trauma” organized by University of Zagreb. You can find her on Instagram and Facebook.

Featured image source: Niyogi Books India