Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for July 2021 is Sustainability. We invite submissions on the diverse aspects of sustainability throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

Consider this. Your favourite actress wears a pair of boot cut jeans on Monday, By Wednesday, you notice that four social media influencers, who believe in fashion therapy, have followed suit. By Saturday, there are roughly thirteen pictures of boot cut jeans on your Instagram feed.

The contemporary techno-social culture has reframed human interaction in itineraries of mental exhaustion. Our ever-present monotony makes us seek refuge in the seemingly interesting lives of celebrities and influencers. We demand new trends from them to extend our definition of the self and become a part of their ‘glamorous’ world.

Expectations of political correctness might compel several social media influencers to post aesthetic pictures with wooden mugs and jute bags, but very few influencers uncover the problematics of (over)consumption, possibly because they, too, have a personal website with merchandise that is always on sale. Our perception of a sustainable lifestyle needs to move beyond discourses on plastic wastage. Let’s also talk about sustainable fashion here

Consequently, the self-proclaimed gurus of social media take it upon themselves to feed our increasing need for content and kinship. In such a digital context, sustainability unfortunately gets reduced to the vocabulary of a trend.

A large proportion of popular discourses on sustainability limit the potential of a sustainable lifestyle to the recycling of plastic. Expectations of political correctness might compel several social media influencers to post aesthetic pictures with wooden mugs and jute bags, but very few influencers uncover the problematics of (over)consumption, possibly because they, too, have a personal website with merchandise that is always on sale.

Our perception of a sustainable lifestyle needs to move beyond discourses on plastic wastage. Let’s also talk about sustainable fashion here.

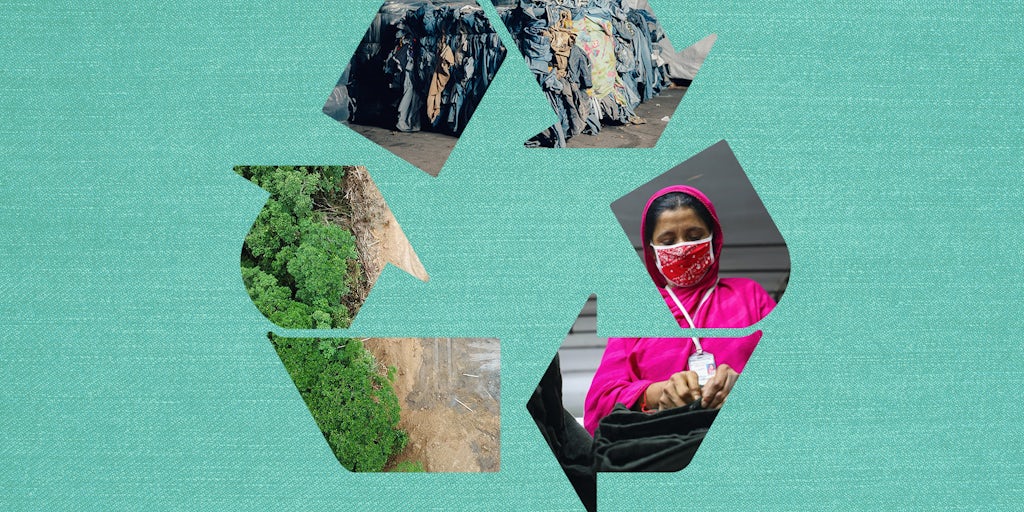

10,000 litres of water is used to make one kilogram of cotton that produces a pair of denim jeans. A person would take roughly ten years to consume the same amount of water. Since trends change with increasing rapidity, clothes purchased as part of a specific trend easily become obsolete, thereby leading to massive waste management issues. The frequency with which fashion trends are generated and discarded shows how fast fashion lives up to its nomenclative potential.

But most of us will not spend over $800 to buy McCartney’s Cropped Knit Sweater. Slow fashion is, in my understanding, a more accessible mode of sustainable living. Simply put, slow fashion involves sharing and renting garments. The foundation of its concept has, unfortunately, been appropriated to establish a profit-making enterprise

Sustainability in fashion is no longer an option. To make sustainable purchasing decisions, consumers need to assess the quality of the garment, the production process, the supply chain, and the garment’s afterlife. The most obvious solution is to limit consumption.

Also read: Why Sustainable Fashion Is A Feminist Issue

There are other alternatives too – invest in ethical fashion garments that last longer, avoid the purchase of outfits with fabric that can negatively impact the environment, do your research on affordable sustainable brands and options, recycle old clothes, share outfits with friends, borrow clothes from family members.

Corporate responses to the urgency of sustainable fashion vary. Some manufacturers have started to develop mechanisms to recycle denim. Lee Jeans, for instance, plans to launch a range of biodegradable jeans that we can put in a compost bin after we decide that we no longer need them. The fabric is 85% cotton and 15% flax.

Megan Eddings, founder of Accel Lifestyle, has developed a proprietary sustainable fabric made of the environment-friendly Supima cotton. Fashion designers across the world have similarly invested in circular fashion and ethical fashion: Sandra Sandor utilises vegan leather and upcycled materials to create dresses and bags, while Stella McCartney focusses on circular solutions to design products for her vegetarian brand.

But most of us will not spend over $800 to buy McCartney’s Cropped Knit Sweater. Slow fashion is, in my understanding, a more accessible mode of sustainable living. Simply put, slow fashion involves sharing and renting garments. The foundation of its concept has, unfortunately, been appropriated to establish a profit-making enterprise.

Several brands have created digital platforms to mediate the process of selling and buying second-hand clothing. Unsurprisingly, most sellers demand a fairly high price for their outfits. If you, for instance, decide to sell a shirt that cost you Rs. 1000, it is likely that you might expect at least Rs. 700 for the garment. Most sellers think along similar lines.

In addition, purchase decisions are, more often than not, dictated by class and caste prejudices. Our utilitarian mindset encourages us to make the best of slow fashion. Consequently, aesthetic filters, expensive fabrics, and branded clothes appear most attractive to us. Many sellers, particularly the ones with limited economic resources, do not have access to premium clothing in the manner some of us do

Here is the problem, though. While expecting profit from sustainable practices, we tend to forget that sustainability is a necessity, not an opportunity for money-making. Further, since slow fashion has not gained incredible popularity, many consumers tend to remain skeptical in their decision-making processes.

Many of us, for instance, would rather buy a new garment or product worth Rs. 700 than purchase an old one. To make sustainability an accessible and non-performative practice, it is significant to forgo expectations of financial profit.

In addition, purchase decisions are, more often than not, dictated by class and caste prejudices. Our utilitarian mindset encourages us to make the best of slow fashion. Consequently, aesthetic filters, expensive fabrics, and branded clothes appear most attractive to us.

Many sellers, particularly the ones with limited economic resources, do not have access to premium clothing in the manner some of us do. Therefore, we need to orient our purchase decisions in egalitarian frameworks that transcend class and caste divides.

Imagine what it might feel like to be a part of a small community of friends who share and lend their garments to each other for free. What if one such small community encourages the establishment of others? Such a trend can foster relationships, promote community building, and advance sustainable lifestyles.

Also read: Why Women Workers Are Protesting Against H&M

Trends introduced by elite celebrities and influencers often wrap sustainability in the rhetoric of Western consumption patterns that might not retain their relevance in India, or South Asia at large. Let’s transform sustainability, sustainable fashion in particular, one step at a time. Sustainability cannot just remain a buzzword.

Featured Image Source: The Italian Reve

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a researcher and a writer. Her work lies in the intersection of feminist theory, postcolonial studies, and popular culture.