The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

These words by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie cautions the readers about the power that stories have and how a single narrative can shape opinions and perspectives of a larger generation, which may or may not be the truth.

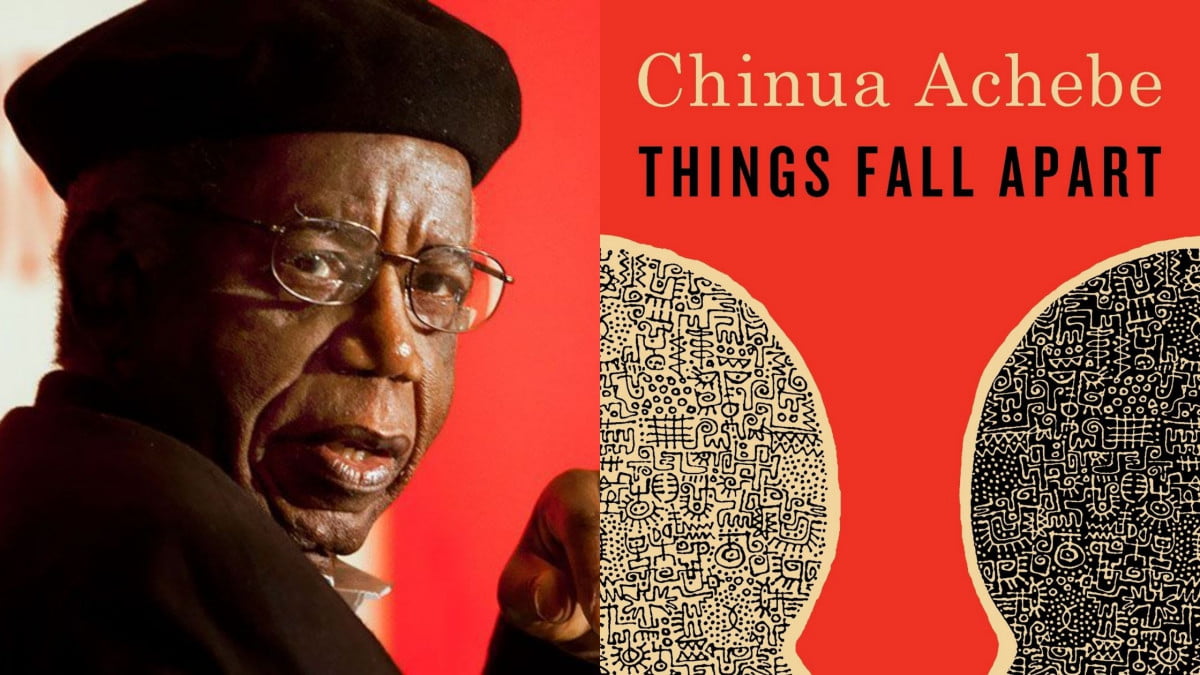

Chinua Achebe is the most celebrated and renowned African author. He is also considered to be the Father of African literature. Achebe’s first novel Things Fall Apart (1958), is considered to be the most important work by an African author.

Over five million copies of the book have been sold and it has been translated into thirty languages. Such is the impact and readership of Achebe, who, according to many critics his writing, ‘marked the beginning of modern African literature’.

Born in an Igbo society, his writings were heavily influenced by Igbo traditions. They drew from folk tales and proverbs, and questioned Western ideas of Africa. A firm believer of the power of stories, he wrote his first novel, Things Fall Apart as a response and an antithesis to Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad and similar works by other European writers.

Chinua Achebe criticises Joseph Conrad for his racist stereotyping of the continent and people of Africa. He claims that Conrad propagated the “dominant image of Africa in the Western imagination” rather than portraying the continent in its truest form. But a feminist reading of Things Fall Apart holds Achebe guilty of the same offence.

Things Fall Apart opens with the character Okonkwo’s predicament. The young Okonkwo, having inherited nothing from his father ‘neither . . . a barn nor a title, nor even a young wife’, to quote from the book itself, has come to borrow seed yams from his clansman, Nwakibie.

The fact that a wife is mentioned in the same sentence along with inanimate objects like barn and title, is enough to give the readers a premonition of the appalling and at times absent status of women in the story. One where they are, ‘down on one knee’ in front of the male folks, silently accepting and surviving in their position as objects that add to the status of an Umuofian( Umuofia is the place where the story is set) male.

In Okonkwo’s case, he was lucky enough to have, ‘a large barn full of yams and three wives’.

Other than to add to men’s status, the women in Umuofian society rarely exist as individual beings capable of commanding power and respect, except the powerful priestess of Agbala, Chielo. To further show their social insignificance, Achebe does not even bother to name Okonkwo’s wives until the narrative is well underway.

At the end of chapter one of Things Fall Apart, they are merely numbers, representing a minor part of Okonkwo’s achievements. It is not until chapter four that Okonkwo’s first wife is called ‘Nwoye’s mother’ and his third ‘Ojiugo’. His second wife is not named Ekwefi until after she has, in anonymity, first been beaten and then narrowly escaped murder by Okonkwo.

While the male characters show depth of character, the female characters are presented as shadowy figures except for Ekwefi, her daughter Ezinma, and Chielo.

Ekwefi and Ezinma exist in the novel to show that Okonkwo, who comes across as a man with a violent temperament, can also have tender feelings, thus retaining the reader’s sympathy. Chielo is the one woman in Umofia who has power but the ‘Chielo–Ezinma episode’ drives home the idea that women in power get despotic and irresponsible because they are irrational.

This gender politics in Things Fall Apart makes one question Achebe’s opposition to the ‘stripping of dignity of the Africans by colonisers’ because in the novel, he does not even once try to attribute power or dignity to the Umofian women. He can also be criticised for inauthentic representation of male-female power relations in pre-colonial Igbo society, as he masculinised the water goddess, Idemili and referred to her as “god of water” in Things Fall Apart.

The effect that the absence of women from the main culture and society in Things Fall Apart had, is that it legitimised the process where women were excluded from post-colonial politics and public affairs through its representation of pre-colonial Igbo society as governed entirely by men

It is important to note that Idemili is considered to be ‘the central religious deity’ and epitomises the matriarchal principles of the Igbo community. By not focusing on Igbo traditions like the Ekwe title, which was accorded to prosperous, self-made women, and by talking solely about male titles and male councils, one can see that Achebe’s narrative of Igbo society in Things Fall Apart is not balanced or free from gender bias.

Furthermore, the female characters in Things Fall Apart rarely speak up for themselves and have no sense of authority even in the face of the arrival of a new religion and the subsequent colonisation, which in reality, is not true. In Nigeria, there were mass protests by Igbo women against the British and their agents which began in 1925 and culminated in the Women’s War of 1929–30.

Also read: Women, Race & Class: Angela Davis And The Women’s Movement In India

The effect that the absence of women from the main culture and society in Things Fall Apart had, is that it legitimised the process where women were excluded from post-colonial politics and public affairs through its representation of pre-colonial Igbo society as governed entirely by men.

Things Fall Apart as a novel, is applauded for being an unbiased and true portrayal of the Igbo society as Achebe does not idealise the society and criticises many Igbo practices like the practice of twin killing and the discrimination against the osu caste. But his criticism does not encompass the condition of women in Umuofia.

Thus, what we get is a story of dilemmas and struggles of men, where women are either silent or silenced, at times through violent measures. Achebe may have been successful in restoring the ‘dignity and self-respect’ of African consciousness, but he never attempts to do the same in the case of African women in this novel.

Through Things Fall Apart, he presents the world with a single story of Africa – one that is dominated by men. One that Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie cautioned the world against.

When we reject the single-story, when we realise that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Also read: Holding Adichie’s Feminism Accountable: Imagining A Revolutionary Feminist Space

References:

- H. I. B. Moody, Elizabeth Gunner and Edward Finnegan, A Teacher’s Guide to African Literature, London: Macmillan, 1984, p. vii

- Amadiume, Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society, London: Zed, 1987, p. 121

Vaishnavi Pal is a Miranda House graduate, currently a Teach for India fellow in Bangalore. When she is not hoarding books, which she plans on reading one day, she is found talking about women in literature, poetry, feminism and her lovely students. An amateur writer and mental health enthusiast, she finds solace in the company of books and Rahman songs. A firm believer in the equality of all genders, she wishes to study gender and contribute her share to the struggle for equality. You may find her on Instagram

Featured Image Source: Bookish Santa