Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for July 2021 is Sustainability. We invite submissions on the diverse aspects of sustainability throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

When people hear the term “sustainability” or “environmental activism”, it is often understood as elitist and privileged, mainly because the discourse lacks self representative, marginalised voices.

When Adivasis or Dalits speak for environmental protection and sustainability, it is often reduced as identity politics by the mainstream. But in reality, the most self sustainable models of development and lifestyle can be learnt from the Adivasis. We can observe minimalistic, gender fluid fashion in their clothing aesthetics too. It confronts the core of the sustainability argument – the problem of overconsumption of raw materials.

In urban spaces, the economic middle class, most importantly the working class who do hard labour, have been practicing sustainable clothing, perhaps without even being aware of it. This article discusses one such working-class dress as a sustainable, zero waste clothing – the lungi.

Although the fashion industry is working on producing affordable organic clothing, sustainable clothing brands are yet to reach the common markets. One of the most important aspects of sustainability is affordability and longevity of the commodity, which would encourage people to use the product. The question that persists is, “are sustainable clothes (produced by big brands) tensile enough for people who do hard labour?”

Most common definitions of sustainability talk about investing in renewable and minimalistic products, so that the future generations do not have to struggle for their fundamental necessities. In short, slowing down the process of consuming and exhausting the finite resources we have.

It takes a hefty investment in the process of mass production of clean energy and preservation of terminable energy. This usually makes the general public withdraw their participation from the narrative of sustainability. The same can be applied to sustainable clothing.

Although the fashion industry is working on producing affordable organic clothing, sustainable clothing brands are yet to reach the common markets. One of the most important aspects of sustainability is affordability and longevity of the commodity, which would encourage people to use the product. The question that persists is, “are sustainable clothes (produced by big brands) tensile enough for people who do hard labour?”

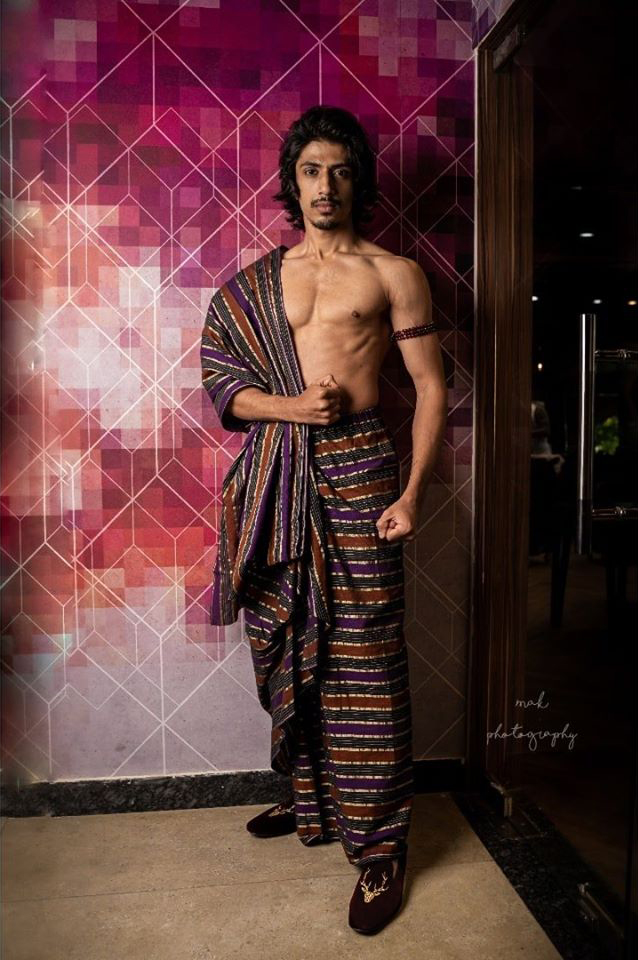

When pondering about this question, I came across Purushu Arie, designer and founder of one of India’s most important gender fluid fashion labels. His designs based on lungi inspired me to sport the wear to my university, which does not have any mandate for clothing. People of all genders wear whatever is comfortable for them, without being moral policed by anyone. I expected the same treatment for lungi too, but to my surprise, it shocked the authorities.

My only persisting question was, “When veshti and sarees are allowed to be sported freely in classroom and academia as ethnic dresses, why isn’t lungi allowed?” It was a new lungi, and it covered all of my body. There was no fodder for provocation or distraction.

This bias made me delve deeper into the politics of the lungi. If the prejudice is due to the conditioning that lungis are meant to be worn at home, have we not seen working class people sporting it for their daily labour?

Western attires are often preferred in academia, even in spaces that discuss post-colonialism and its politics. It is understandable when this happens in the science streams, where there is no space for sociological discussions. But even humanities and social sciences restrict students from decolonising their minds.

Hypocritically, it is acceptable in academia for Sanskrit faculty to sport their traditional wear, mostly white dhotis. Even the colour of the loincloth plays a role in identifying one’s social location.

While the lungi is a traditional wear in Myanmar and a normal wear during worship by the Muslims, it is unaccepted by many temples across India. This is due to the affiliation of lungis with the working castes, who are often Bahujan. What is accepted by one religion in spaces including those of worship is unwelcomed by another, and it doesn’t stop there.

Lungi is sustainable – it is a zero-waste clothing that leaves nothing behind. Every part of it is fully utilised in the making and it consumes lesser water to produce when compared to Jeans, which was originally part of trickle up fashion. It is mostly weaved by underpaid workers in their small-scale factories, which was then appropriated by large scale corporates and owners of bigger labels. Therefore, it is also essential for us to resist the invisibilisation of its social significance

An extension of this is what can be seen in central university campuses as I have already mentioned. It raises various questions, one of which is, whether the aversion towards lungi springs from closeted or internalised islamophobia.

Image: Kamat’s Potpourri

As Purushu Arie notes, “…Inclusivity still hasn’t reflected in power structures controlling the fashion industry and therefore, the inspirations continue to be largely elitist, urban, and white (or Brahminical in Indian context). Any attempt at drawing trickle up inspirations by such non-diverse, white/Brahminical groups often leads to a case of cultural appropriation and theft with no representation of the community from whom the style/culture originated.“

Lungi is sustainable – it is a zero-waste clothing that leaves nothing behind. Every part of it is fully utilised in the making and it consumes lesser water to produce when compared to Jeans, which was originally part of trickle up fashion. It is mostly weaved by underpaid workers in their small-scale factories, which was then appropriated by large scale corporates and owners of bigger labels. Therefore, it is also essential for us to resist the invisibilisation of its social significance.

Also read: Cleanliness Is Political: How Caste Dictates Discriminatory Notions Of Pure And Impure

“Trickle up fashion’s celebration of oneness itself should not be mistaken for lack of individualism. Historically, trickle up revolutions like Punk, Hippie, Dravidian Self-Respect movement etc. gave us new ideas that were individualistic, rebellious, liberating, experimental, and critical of tradition“, notes Arie’s website post on fashion trends.

Purushu Arie also speaks about the historical and gender neutral aspects of lungi. He says, “Lungi boasts of a far bigger trade history and global presence than vettis. As early as in the 12th century, Thamizh traders exported small checkered scarves to the Middle-East where it was known by the Persian word “Loongee”. Waist-wrap garments known as “kaili” or “saaram” in Thamizh, were discovered by the East India Company in the 17th century. Checkered kaili was popularly worn by Muslim men, and was also cut up and made into tight-fitting bodices by Thamizh women.“

the centralisation of the zero waste product lungi doesn’t just pave way to sustainability but also the deconstruction of power relations in fashion. But the only question remaining is, “will lungi ever be accepted by the mainstream society, even if it is one of the most cost-efficient ways to sustainable fashion?

This rich significance was brought back to spotlight when late Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Annadurai started giving interviews in his lungi. It was an act of political rebellion in clothing, to not just normalise but also underscore the ethnic significance of lungi. After a major gap, Karnan (2021), a Tamil feature film directed by Mari Selvaraj did that work for lungi where the hero Dhanush was seen in lungi throughout the film.

Purushu Arie mentions, “In Mari Selvaraj’s Karnan, the elderly people who are accustomed to the bullying of dominant castes wear vetti & thundu to dress on par with savarna supremacy. In contrary, the more rebellious youngsters of Puliyankulam are depicted in lungis – where the fabric symbolises their non-conformity to the established sartorial politics.”

Thus, the centralisation of the zero waste product lungi doesn’t just pave way to sustainability but also the deconstruction of power relations in fashion. But the only question that remains is, “will lungi ever be accepted by the mainstream society, even if it is one of the most cost-efficient ways to sustainable fashion?”

Also read: Elite Sustainability: Devaluing Local Food Practices To Match The West

Arunesh X is a Dalit writer, theatre artist, Dalit studies/ masculinities studies scholar, intersectional feminist and Dalit activist, who completed Masters from the Pondicherry University. He has worked as the Editor at the Oxford University Press, India. He writes his fiction and poetry under the pen name Hsenura. You may find him on Instagram.