Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for July 2021 is Sustainability. We invite submissions on the diverse aspects of sustainability throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

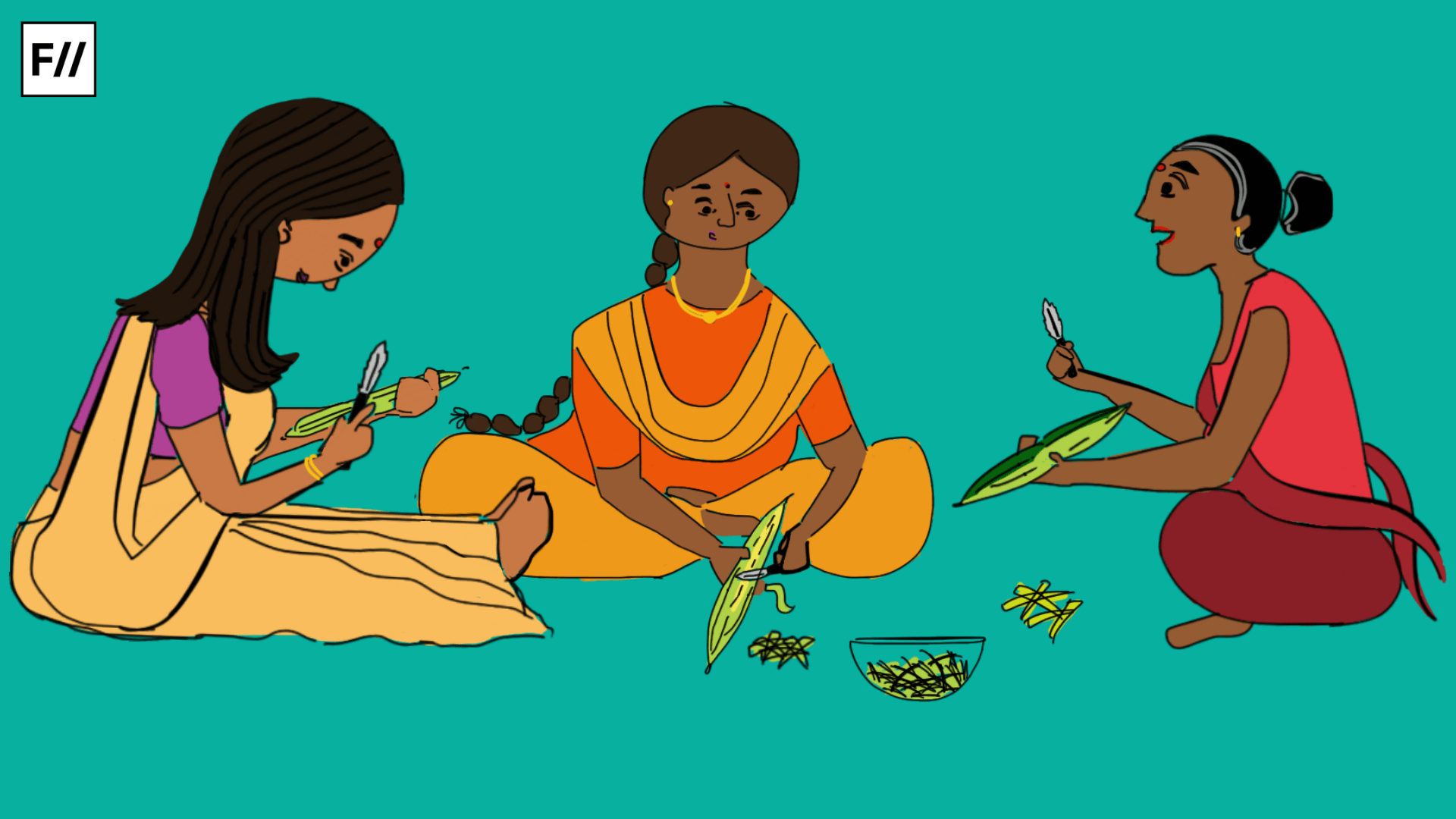

Food is never just about a set of nutrients or health benefits. Our food platter represents our taste preferences, culinary traditions and social norms. Our dietary and food habits are no doubt not only shaped by these cultural factors, but by ecological and agricultural factors as well.

Our inclination towards different food items and food habits is dispersed both geographically and economically with regards to other important factors such as our physiological capacities, subjective motivations and feelings embodied in a particular food such as affection, sensuality, pleasure, rejection etc.

But, no food item other than “meat” has has become an important point of discussion in our public discourse in recent times. Also, hen we speak about food consumption through the lens of sustainability, “meat” consumption has attained the center stage of debates due to the political, moral economy involved with it.

in order to understand and reduce the ecological repercussions of “meat” consumption in the Indian context, we need to delve into the material, cultural contexts of it, and the various layers associated with this particular food habit in the Indian subcontinent

The availability and the consumption of meat are diverse and dispersed in our country. It is of no doubt that, higher “meat” consumption will resultantly lead to higher factory based livestock farming, which will ultimately lead to greater ecological crises, loss of biodiversity, land degradation, desertification and greenhouse gases.

Nonetheless, changing human behaviors purely based on ecological concerns and environmental hazards is quite impractical. Human behavior does change due to external motivations and reasons. Here, we are talking about human consumption in which case such drastic changes are highly unlikely to happen.

Also read: Veganism Has To Do More With Caste-Class Privilege, Than Animal Rights

People who are willing and motivated to change to veganism and vegetarianism simply based on ecological concerns are quite a minority even in Western societies. Thus, in order to understand and reduce the ecological repercussions of “meat“ consumption in the Indian context, we need to delve into the material, cultural contexts of it, and the various layers associated with this particular food habit in the Indian subcontinent.

Michael Bruckert notes in his work Food and Sustainability in the Twenty first Century: Cross Disciplinary Perspectives, that when looked through an economic perspective, eating “meat“ is considered quite expensive. For young men to indulge in meat eating and that to different types of meat also represents their boldness and masculinity.

strictly restricting individual food choices to reduce and curb the environmental crisis could never be a feasible solution, especially when we consider that food, consumption practices and nutritional choices are also governed by access, privilege and social positioning

Some of the minority communities and tribal societies take up “meat” consumption as an assertion of cultural pride and resistance to the hegemonic and oppressive ideals endorsed by the upper castes. Bruckert mentions that eating meat is also considered as an act of dissent against religious conservatism.

As the exceeding accessibility, visibility and consumption of meat got further acquainted and internalised with power and strength, it led to the consumption of meat as a practice associated to only certain social and economic locations. Not to forget, some members of the upper class make their non- vegetarian food choices in public places as a marker of their freedom and cosmopolitanism.

Also read: We Must Be Mindful Of Privilege Before Putting The Burden Of Sustainability On Meat Eaters

Thus, strictly restricting individual food choices to reduce and curb the environmental crisis could never be a feasible solution, especially when we consider that food, consumption practices and nutritional choices are also governed by access, privilege and social positioning. Millions of people depend on livestock farming for their sustenance and employment.

Due to extreme stress on veganism, vegetarianism and associated food policies for sustainability, these communities are left on their own with no other options or sources of nutrition for them.

For a long part of our history, the dominant castes have always tyrannised the meat eating communities, and have used several dietary taboos to stigmatise and intimidate them. The current political regime channelises on hateful campaigns which not only target the “meat-eating” consumers, but also identifies them differently.

Thus, our individual choices of food may not take us far in the sustainability journey if we do not acknowledge the social, political and economic context of why certain types of food are consumed. To severely blame vulnerable, marginalised communities who have no choice or social capital to opt for alternatives will not fix the problem.

So, now it is up to the privileged, well-off among us to alter our choices. We must be ready to walk our talk of defending the marginalised by taking on more of the onus of sustainability. It is the responsibility that comes with privilege and not a grand gesture or favour. We are here as a collective and we must act like it.

References:

Sabate. S Ruben & Sabate Joan, Consumer Attitudes towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review ,International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, April 2019

Bruckert. Michael, Food and Sustainability in the Twenty first Century: Cross Disciplinary Perspectives, Berghahn books,2019

Krittika is an educator, writer and independent researcher. Her areas of interest are food, gender, sexuality and sustainability. Currently, she is an educator at Myra Ek Pahel, and passionately involved with “Dubara”, a citizen driven engagement project for building sustainable practices in urban places. You may find her on Facebook and LinkedIn.