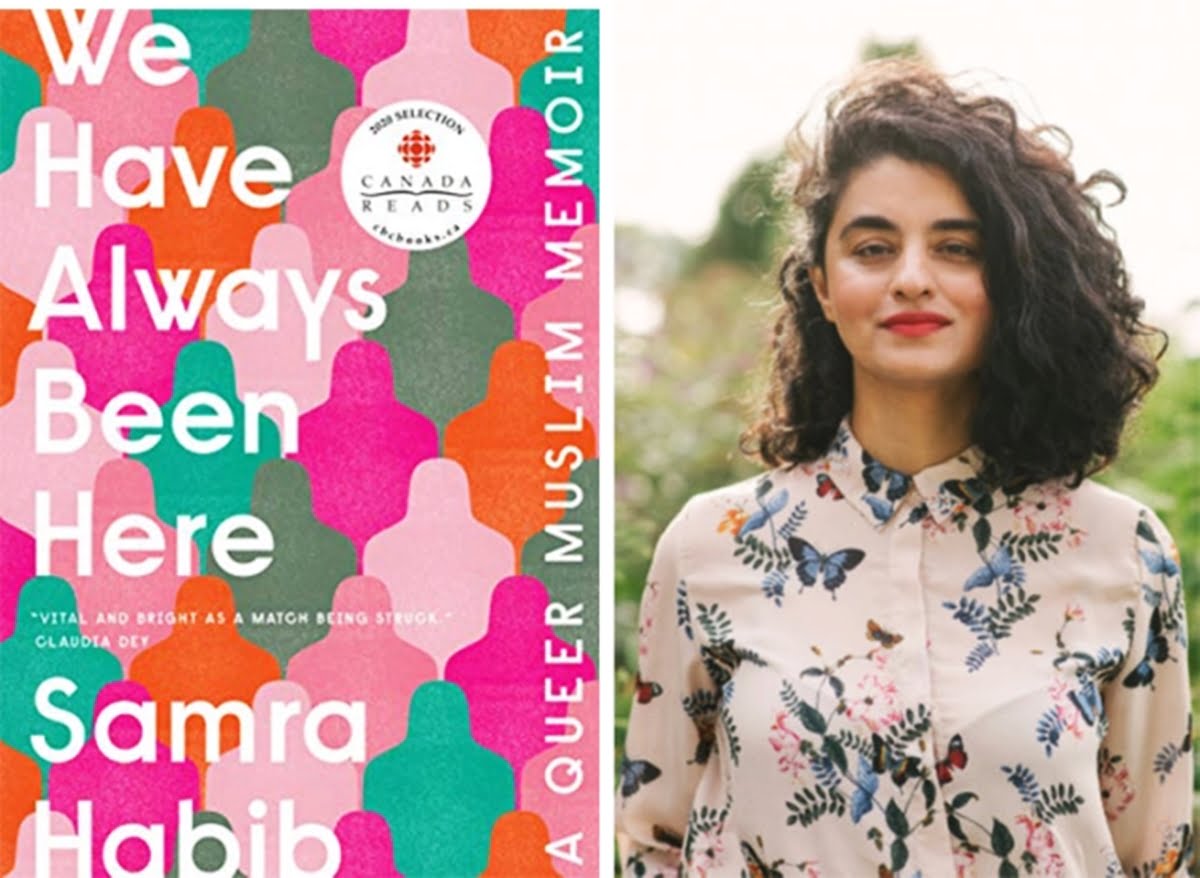

We Have Always Been Here by Samra Habib, published by Penguin Random House, Canada in 2019, is the gateway to understanding the question of visibility. A memoir that traces the journey of a queer Muslim, the book oscillates between the subject of the identity-web and freedom of self-expression. Navigating a range of spatial logic, the book is about Samra Habib, a Pakistani-Canadian photographer, and her experience as a queer-identified Muslim woman who spent years in search of something as basic as “safety”, which by the virtue of being a human is the bare minimum one can expect of: from one’s country, society and community. Yet the matrix of identity within which individuals and groups are caught is such that safety and security continue to remain a far-fetched dream for so many.

Navigating a range of spatial logic, the book is about Samra Habib, a Pakistani-Canadian photographer, and her experience as a queer-identified Muslim woman who spent years in search of something as basic as “safety”, which by the virtue of being a human is the bare minimum one can expect of: from one’s country, society and community.

Samra Habib spent her early years in Pakistan, born to Ahmadi Muslims parents, a sect that has faced denouncement and continues to remain a target for religious persecution due to their differing beliefs from the general Islamic preaching. While that identity traps Samra in one way, the process of coming to terms with her queerness is another facet which complicates her identity in a society wherein homosexuality is still a crime.

Also read: Book Review| Things Fall Apart: Chinua Achebe’s Masterpiece That Fails To Represent Women

Thus the legal and social constraints suffocates the very existence of a being, in that the very act of realising the self, being true to oneself becomes an act of rebellion, inviting the wrath of the social order and the state. In that atmosphere, how does one ever find the scope for self-expression. The entire process of moving towards freedom of self-expression is further rendered tortuous when the family gets your marriage arranged in early teens, even before you have come out to them- a chance at cultural preservation in a foreign territory: this is presented as Samra’s fate and this line runs through the palms of the tales of so many other people that we will never know about.

In the subsequent years, Samra Habib’s family moves to Canada to escape religious persecution, in search of a better life and economic prospects, and while Samra vividly describes the process of immigration, there is a tinge of hope and yet sadness, simultaneously as she comes to the realization that one is leaving behind her home, treated like some alien at the airport on arrival, and yet there is hope for an outlet of the being. However, the journey is never an easy one, as she battles the traditional outlook of the family, on one hand and on the other hand, the compulsion to mingle with the crowd, to become one of them.

“I was no longer teased for being ‘other’ because we were all different in our own ways. Looking different and sounding different and being different were no longer impediments to walking down the hallway or eating lunch in the cafeteria in peace”, Samra Habib writes.

While the hope to find a better world is met with some breaks, with rampant racism and at times growing homophobia, the sense of a loss, of a home, spurts out constantly in the tone of the book, making one wake up to the realization that identity is one such web which had already been woven for us and this fixation made the pursuit of one’s identity more limited, in the sense one cannot overnight break free on will. Samra is quick to observe that people in the West (here Canada, a multicultural nation and one of the first countries to legalize same-sex marriage) too live in a bubble, seduced by the illusion of equality and that they did not see the need for a project that potentially might accentuate the struggles of queer Muslims, for they were under the impression that things were great for all the LGBTQI+ community in the country.

Moreover, the timeline of her stay in the West coincides with 9/11 which had repercussions for Muslims in myriad ways, so much so that one had to at times spell out one’s name in ways that would not sound like a Muslim name. The search for safety thus remained a constant search. However, what is heart-warming is the sense of community and solidarity as an upshot of the social circle that Samra Habib finds herself as a part of, while for her parents that sense of community comes in the form of being a part of the diaspora circles of similar kind that felt like home away from home.

In later years, as Samra comes out to her family, the act is nothing short of a paradigmatic shift, as her family is forced to imagine a world they never thought had existed- or simply like many others had chosen to un-see, to overlook, to invisibilise. Yet the title asserts “we have always been here”.

Returning to the point of shared solidarity, Samra Habib becomes a part of these networks and groups which have taken on the responsibility to offer refuge and provide safety to the queer community in the arms of religion. They have created places of worship, wherein people from any background, identity or ethnicity can come, gather and pray together. Instead of focusing on the literal rituals, the focus is more on understanding religion as a warm and welcoming space for healing, wherein the relationship between God and the individual is immediate and unmediated- wherein one can just be, in their absolute crude form, and bare one’s heart open to God, in just the bare form that God had created one, devoid of identities that later came to be added layer by layer.

This becomes so pivotal in the face of overlapping identities and as much as one would want to deny but the interplay of one’s religion, sexual orientation, the native place and the country where one settles in- are important for some; for some these are the roots of belonging, markers of identification.

“The reality is that this identity has shaped the way I see the world, and the way others see me, in a way that is beyond my control. Being Muslim is one of the only absolutes about myself I can be sure of. It serves as an anchor when I am lost at sea. It helps me come back to myself, and it leads me to others who’ve struggled to reconcile seemingly disparate parts of themselves.” writes Samra Habib.

Also read: Book Review l Dragman: A Graphic Novel About A Cross-Dressing Superhero

The discussion on Unity Mosque thus serves as a crucial reminder of how the society has treated the gender-non conforming individuals and has shut the door of religion on their faces, making religion an exclusionary space. Spaces like Unity Mosque undo exactly that hurt of rejection, where one is accepted and seen, especially for those who hold religion and their bond with the Creator as dearer to the self.

This idea then helps Samra Habib build her career to the next level, wherein she conceives this project called “Just me and Allah”. The project basically is about capturing similar struggles and narratives of Queer Muslims from all over the world. Samra has traveled to diverse nations to meet people with similar struggles, to listen to their stories and to bring the stories in front of the world through her lens to assert and testify that “we have always been here”. The project further hits on the idea of homogeneity found within religion and instead brings to the table a more nuanced and layered understanding of Muslims.

Samra Habib does good to accentuate yet another exclusionary space- the academia, which is inclusive in the sense of understanding queer struggles, when it comes to theorizations and discussions but the very academic language creates emotional barriers- a language that is “inaccessible to those who need to be comforted most”.

Samra Habib does good to accentuate yet another exclusionary space- the academia, which is inclusive in the sense of understanding queer struggles, when it comes to theorizations and discussions but the very academic language creates emotional barriers- a language that is “inaccessible to those who need to be comforted most”.

In Samra’s words, which best sums it up, “Queer Muslims who fear for their lives every day- while walking down the streets of Punjabi villages or meeting a potential love interest for the first time in Tehran through a dating app- might not have the tools to understand the language written by academics in Ivy League schools”. The question of spaces, of representation thus become critical in reminding the world that they have always existed!

If there is a note of hope that one should be left with, the book will offer you many; if you are looking for revolution, the book will speak to you in its own terms. While not everyone is privileged to commit oneself to political activism in the conventional sense, the emphasis however is on a life dedicated to understanding oneself, which for so many, “can be its own form of protest, especially when the world tells you that you don’t exist”.

About the author(s)

Sana is a research scholar in Political theory, which also happens to be her love of the life. An avid reader, she aspires for a career where she would be paid for reading and reading. With a passion for reading "acknowledgement pages and dedications" by the authors in their books, She hopes to establish an archive of acknowledgement pages one day.