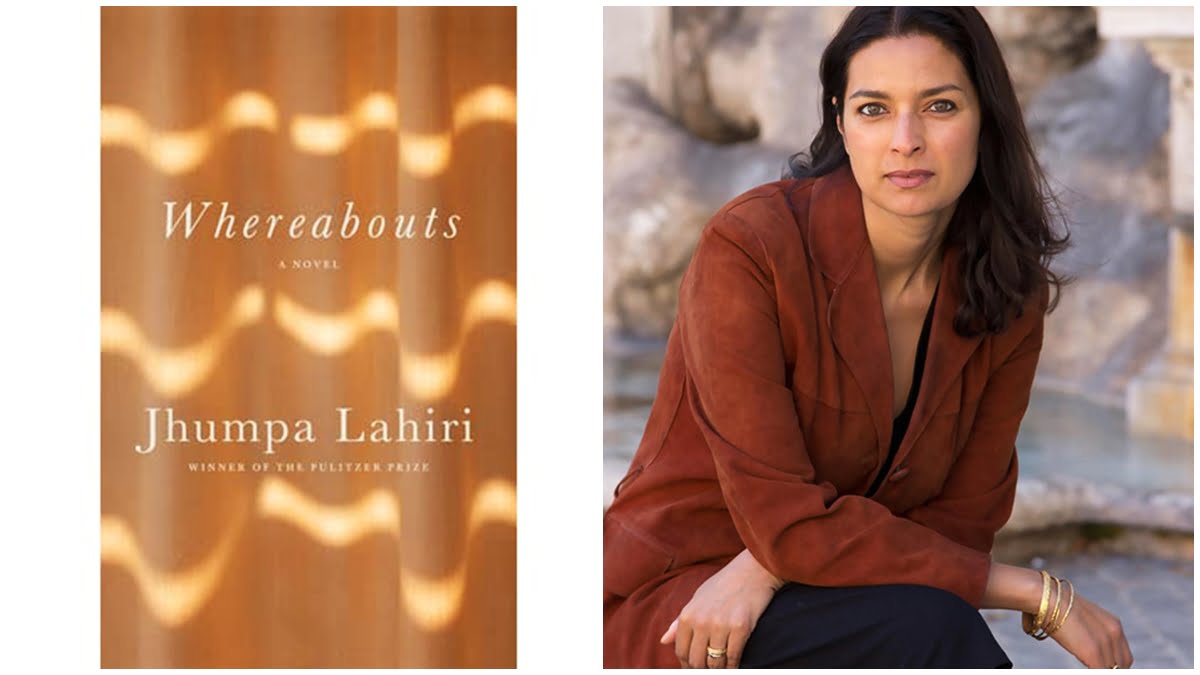

Perhaps the scariest feeling one could foster reading the lonely vignettes of a middle-aged woman is a stirring sense of relatability. Reading Jhumpa Lahiri’s 2018 novel, Whereabouts, is when I had this experience – mostly as a constant, discomforting buzz, but sometimes as episodes of uncanny, specific reflections.

It can’t be ideal for a 24-year-old woman to have the same thoughts as a nameless 40-something. Surely not healthy for her to concern herself with the same things while harbouring a similar sense of depletion – as if life in its glory has been lived?

Perhaps the scariest feeling one could foster reading the lonely vignettes of a middle-aged woman is a stirring sense of relatability. Reading Jhumpa Lahiri’s 2018 novel, Whereabouts, is when I had this experience – mostly as a constant, discomforting buzz, but sometimes as episodes of uncanny, specific reflections.

The beginning of Whereabouts slowly establishes her solitude– taking the reader to a few episodes of her past and the relationship she shared with her parents. The latter emerges as an important underlying theme, surfacing now and then. There is a friend she vaguely likes and imagines having an affair with (a nameless Him). Another friend is a successful businesswoman who has to travel frequently and does so with ease, as she wishes to escape her family. We see in these descriptions, implicit, subtle what-ifs. What if she had chosen to spend her life with Him and have a family? Would she be happy? Would she too, need to escape it from time to time?

Also read: Book Review: The Namesake By Jhumpa Lahiri

In Whereabouts, she encounters people she deems like herself, some of whom seem to be living gracefully. Then there are those that are more expressive of their woes. Waiting on a bench in a hospital, she sees an older woman and imagines herself to be in her state soon – with no one to care for her. This foreboding sense of loneliness is what I felt throughout reading Whereabouts. Most of it feels like a stagnant lake, studded with momentary company – there is the pool she swims at where she meets older ladies with their familial worries, there is a salon where she is taken by a new employee, there is a stationery, a stranger, a dog. It is clear that solitude is her permanent reality and these elements fill the gaps in it from time to time to keep it intact, to prevent it from deflating and descending like a tired balloon.

We think we can live alone (and surely, practically we can), but we undermine its effect on us in the long run. We undermine the actual passage of time we will have to spend in our companies. The years compound and we remain nothing of the independent, self-sufficient people we imagined ourselves to be. There are more lows than highs, and few have the resilience to bear with themselves and their churning minds.

While regret is a heavy word, we all have things we could’ve done differently or simply things we could’ve done which an age allowed but didn’t. As our narrator contrasts her 16-year-old self with a friend’s daughter she is meeting, a saddening sense of loss comes over her. ‘I didn’t like myself, and something told me I’d end up alone.’ At the cusp of my life’s beginning, I am already conjuring up these contrasts with my past self, with a dreadful deeper knowledge of an all too plausible depressing future. This future is nothing but a stretched present. I understand that this may be a time that’s not in my favour, but it is hard for me to imagine there ever will come a time that will be.

With solitude comes the incessant wonderment of those who portray a similar air as us. We develop abilities to form unspoken bonds with another lonely person with kind eyes. The mere presence of those eyes and an acknowledging nod can make one feel at ease. It is almost like deriving comfort off a mirror.

Themes of banality and meaninglessness also surface toward the middle of Whereabouts. Most of the chapters feel simple, but upon deeper interpretation, reveal that she may be trying to fix her despondency with objects, vacations and gatherings. Most of it, however, is a meek attempt at filling time and entertaining oneself through another day. The thing at the centre of her plight remains untouched. The woman recalls her childhood, her relationship with her father and mother frequently. The episodes with the latter emerge as untended wounds. It is scary to imagine that the impact our parents have on us continues to drill deep orifices within us that echo decades into our adulthood.

Themes of banality and meaninglessness also surface toward the middle of Whereabouts. Most of the chapters feel simple, but upon deeper interpretation, reveal that she may be trying to fix her despondency with objects, vacations and gatherings. Most of it, however, is a meek attempt at filling time and entertaining oneself through another day.

Tempestuous memories zoom by, keeping them alive. I have always imagined that it perishes with time, but it seems the most it can do is fade. Rocks of knowledge, realisations, unlearning, reparenting and endless scrutiny are altogether not enough to entirely destruct them. You could try to close their ends with landslid mountains, but it remains ever capable of echoes, ever a hollow – a part of you that has been scooped out and which cannot possibly be stuffed with filler.

It strikes me that not resolving these complex relationships through communication and therapy has ill effects that persist long after one departs from one’s parents. The sooner we realise it, the more effort we take to tend to our inner child, the better our adulthood would be.

While I think I may only have been able to appreciate a book like this after a certain age, I feel lucky to be sensitive enough to look at Whereabouts from an emphatic lens. Unwanted relatability was the only factor that kept me going, since most of the writing is in the lowly spirit, appropriate to the subject and hence, sometimes takes on a rambling effect.

Also read:

In the latter chapters of Whereabouts, a change is initiated. She visits her mother before temporarily moving to a foreign city for work. I believe life has the capacity for transformation. If not grand, small. But the real courage lies in accepting that we have been living in a decaying condition, surrounded by things and people that don’t mean much. So when the opportunity presents itself, should we not grab it with some enthusiasm? The woman in Whereabouts does grab it, but with little to no enthusiasm. I understand her because our imagination often corrodes as a result of long spells of melancholy. The dread of having a bad state of mind is that it leads one to believe this is how they will have to live forever.

Before leaving, she spots a woman in the piazza who is dressed exactly like her. She follows her for a while. This double of hers is more cheery, more confident, more sure of her place in the world. She pictures herself staying, she pictures herself going. Where will she be? Would a part of her still linger on here? Here, meaning the city. But here, also meaning the state of mind? I would like to believe she is going to better places and choosing happiness over this lake she has settled into. I hope she is taking charge of her life. I can only say with some conviction that it is possible at 40-something as it is at 24.

Taruna is a writer, illustrator and architect from Jodhpur, Rajasthan. She is an avid reader and has a keen interest in literature, philosophy, art, and culture. You can find her and her works on Instagram, GoodReads and WordPress.

हालाँकि मैने झुम्पा लाहिड़ी का लिखा कुछ भी नहीं पढ़ा मगर समीक्षा के तौर पर मुझे तरुणा खत्री के शब्दों ने प्रभावित किया। उनका लिखा हुआ पढ़ कर किताब के बारे में जिज्ञासा पैदा होती है। किताबों पर लिखना खुद को अभिव्यक्त करने का अच्छा तरीका है।

खूब शुभकामनाएँ।