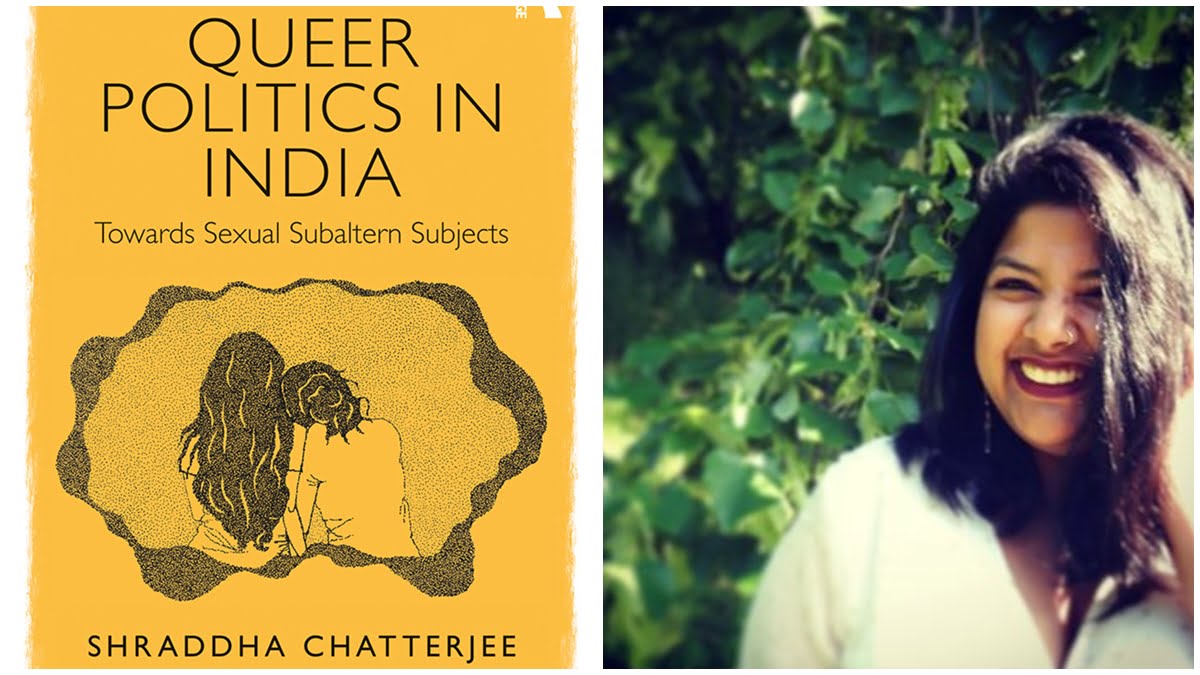

In her book Queer Politics in India: Towards Sexual Subaltern Subjects, Shraddha Chatterjee looks at the failure of queer politics in India to incorporate sexual subaltern subjects in the context of the death by suicide of two women, Swapna and Sucheta. It traces the history of the queer movement in India placed within the universalization of queer subjectivities in tandem with capital, neo-liberal forces which erase intersectional differences. She builds upon feminism and queer politics using arguments by Foucault, the politics of representation and Lacanian Psychoanalysis.

Swapna and Sucheta weren’t present in queer politics yet the politics lay claim on their death, highlighting the theorization of such subjects through a framework of re-presentation as inclusion even though their deaths were seen through the lens of oppression due to poverty and not feminism. An intersectional lens emphasizing gender, caste, and class was completely absent, questioning the place of subjects that aren’t educated, upper class/caste, or able to articulate their identities.

Mapping Queer Politics

Chatterjee traces the origins of the queer movement in India in the late 1980s and early 1990s, pointing towards the first protests and queer rights organizations devoid of any universal truth or critique in Queer Politics in India. While the gay rights movement was placed within disease and sexuality, the lesbian rights movement sprung from the women’s movement, the first space to articulate concern over control of sexuality and the social construction of gender. She covers the discourse surrounding the Lesbian movement where lesbianism was thought of as fracturing Indian womanhood or Indian Feminism.

Shraddha Chatterjee traces the origins of the queer movement in India in the late 1980s and early 1990s, pointing towards the first protests and queer rights organizations devoid of any universal truth or critique in Queer Politics in India.

Section 377 and Queer Politics

The book highlights how Section 377 did not allow the formation of a national symbolic imagination of non-reproductive heterosexuality. Its subsequent removal helps us to engage with India’s colonial history and how as a developing country it rejects sexualities and identities that don’t fit in the globalized narrative. The movement against Section 377 erased lesbians and transgender as representatives of queer subjectivities in India. The text also fails to acknowledge the trans activists who individually led the legal fight against Section 377.

The taxonomy also preferred western terms over local ones and the funding created a politics of inclusion, exclusions, and normativities. Today, the accessibility has increased mostly through an online community but we need to ask who is left behind? Even though the goal of queer politics is inclusive citizenship, it trades off some queer lives for privileges of queer nationalism. This brings up the question of who is a good and legitimate queer subject. Chatterjee opines that even a woman has to be a subject of the patriarchal state to be a beneficiary of legal reform.

Within the discourse surrounding same-sex marriage, recalling that gay men didn’t recognize how patriarchy was oppressive to women, we need to ask – Will same-sex marriage rights make cis gay men and lesbians the subject of the patriarchal state? And if so, what will be the trade-off and who will bear the brunt of it? Furthermore, the argument of sexuality being a private concern also protects domestic violence as a private act, outside the purview of the law.

Also read: Book Review: Beijing Comrades By Bei Tong

Inclusion, Representation, and Re-presentation

Identity politics and queer politics have synced today, given we define queerness as an identity. While Sappho for Equality reconstructed the lives of Swapna and Sucheta, representing the violence of heteronormative sexuality, the media used terms like abnormal togetherness and unhealthy bonding. These instances provide an experience as evidence, which is linked to sexual politics where queerness is an identity, demanding human rights based on identity as a personal choice.

Chatterjee argues that sexuality and gender as personal choices lie outside the ambit of collectivity and if individual choice forms the basis of marginalization, then the demand for human rights essentializes the suffering of the homosexual. The naturalization of queerness places heterosexuality as the natural other. Not only naturalization of queerness erases history and politics but it can negate intersectionality as it becomes difficult to signify any identity completely. There is an urgent need to change the referent of queer politics from heterosexuality and to shift the very language of sexuality.

In highlighting the distinction between the art of inclusion versus being inclusive and representation versus re-presentation, Chatterjee makes it clear that the subaltern can be addressed by feminism but they cannot speak because representation involves institutional power. It cannot be denied that reproductive heterosexuality still governs the lives of queer subjects at the cost of radical queerness. Turning to the discipline of psychoanalysis, she decodes how relations of power and capital allows certain queer subjects to speak for others instead of speaking for them.

Sexual Subaltern Subjects

Chatterjee decodes how the subaltern, seen as devoid of reason, was absent from dominant modes of history and historiography with much epistemic violence and (mis)re-presentation. The task for the subaltern was to reconfigure history to make himself subject of his history, as opposed to being an object. Even within that, women were not considered as central figures with their question being a marginal one instead of a structural one. The subaltern as a citizen of the state can be the subject of a policy, but not influence it. Their agency is also seen as collective, lying outside the framework of individuality.

Queer Politics in India: Towards Sexual Subaltern Subjects is a rich academic text with an unfinished map of queer politics in India that raises critical questions about queer politics, inclusion, and the re-presentation of the sexual subaltern subject.

Chatterjee argues that the idea of subalternity with sexuality captures the politics of subordination, exclusion, and invisibility attached to non-hegemonic sexual identities, something with queer cannot do. Within this framework, Swapna and Sucheta would be sexual subaltern subjects outside the exchange of reproductive heteronormativity and discourses of queerness & sexuality that characterize contemporary queer politics in India, highlighting the limits to politics, theoretical disciplines, discourses and their methodologies on queer experiences.

Also read: Book Review: Gaysia–Adventures In The Queer East By Benjamin Law

Queer Politics in India: Towards Sexual Subaltern Subjects is a rich academic text with an unfinished map of queer politics in India that raises critical questions about queer politics, inclusion, and the re-presentation of the sexual subaltern subject. At the same time, it excludes transgenders, South and North-East India in writing the history of queer politics, which is a gross injustice and a form of discrimination that has been pervasive within academia. Even with ample theorization of the history, subjectivity, and location of the sexual subaltern subject within queer politics, the book fails to include more narratives on gender minorities (of intersex, transgender people).