In July, in a horrific incident, a teenage girl from Uttar Pradesh was reportedly killed by her next of kin for wearing a pair of jeans. Neha Paswan, from the Savreji Kharg village of Deoria district in UP, was reportedly beaten to death by her grandfather and uncles because of her choice of western attire for a traditional ritual at her home. Her murder is one of the many instances of violence against women that get reported in India yet fail to leave an impact.

It goes on to show how patriarchy, by constantly policing women and their bodily autonomy to wear what they choose to, has created an unsafe space for women, not only in public places but in their own homes.

Neha was a 17 year old young woman who liked to dress up in western attire. That went against her family’s cultural decorum. Meanwhile, her rebellious nature was to question such conservative ideals. Her reported death at the hands of her kin because she dared to ‘toe out of the line’ drawn by the patriarchs might now not be as alarming, given how we wake up to several cases of violence against women in India. However, it is integral to the feminist movement that we question: Are we still not done moral policing the girls and their choice to wear what they want? Is the onus of ‘protecting’ the so-called honour of the family still in a woman’s vagina? Why can’t a woman wear pants?

In July, in a horrific incident, a teenage girl from Uttar Pradesh was reportedly killed by her next of kin for wearing a pair of jeans. In this regard, it’s important to understand how this piece of gendered clothing became a part of the women’s liberation movement.

In this regard, it’s important to understand the history of pants; and how this piece of gendered clothing became a part of the women’s liberation movement.

Also read: Why Ripped Jeans Should Become A Symbol Of Women’s Rights In India

The male-female binary of clothing through history

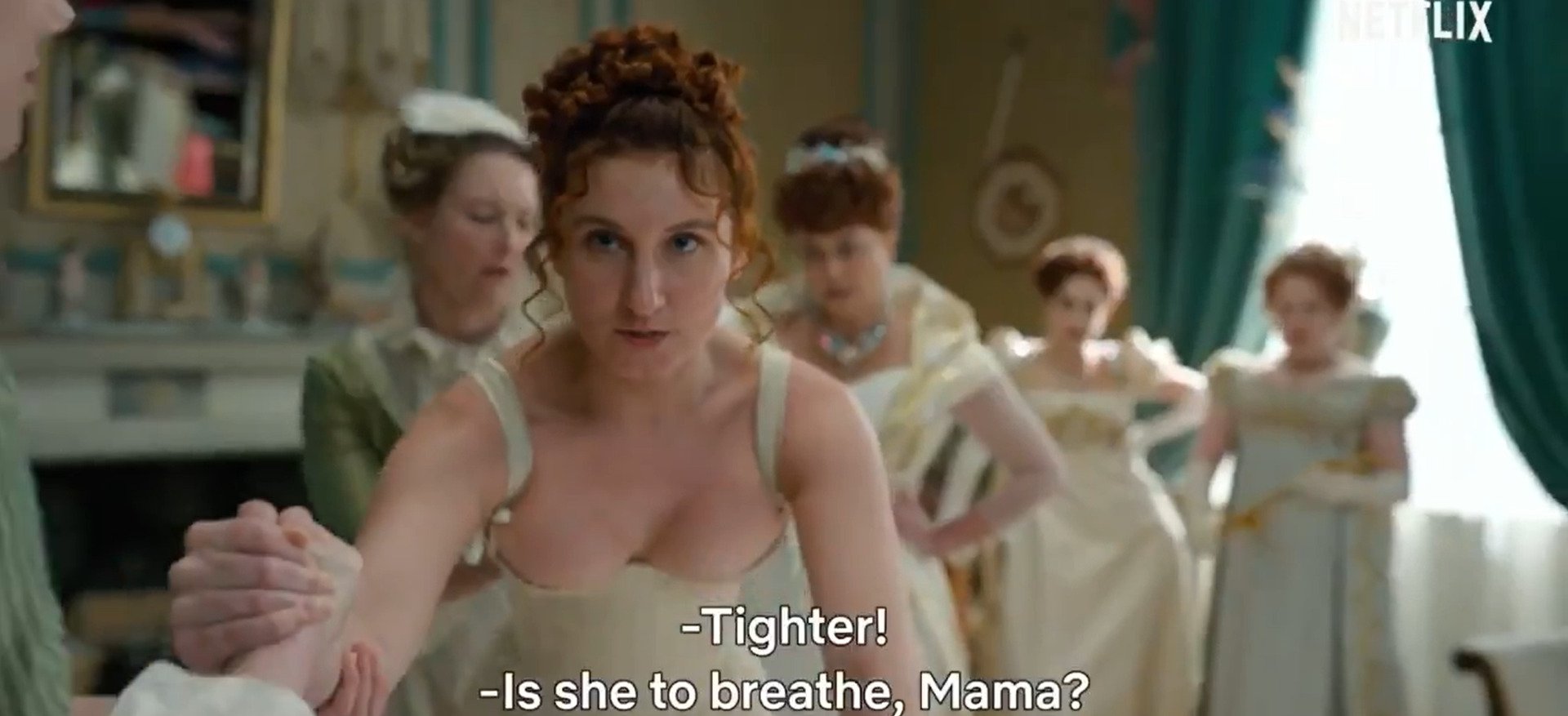

Women’s attire has always been society’s topic of discussion. Throughout history, their sartorial choices have been more closely scrutinised than their male counterpart’s. The feminine and masculine distinction persisted in clothing since the early ages. From the archaic to the modern period, women fashioned some simple to some complex clothing styles. Flowy garments made up of strappy linen clothes, big gowns with corset and bodices, large dresses with a framework of wood underneath and skirts with crinoline petticoats, predominantly made-up women’s apparel.

The geography and culture of a place largely influenced the dressing and clothing style. In India, women dressed up in accordance with the weather, climatic condition and based on one’s caste accorded social status: bare-breasted or draped in saree. This type of convenient clothing was very prevalent in Victorian-era Bengal. However, this changed over time with the introduction of European origin petticoats and blouses.

Modesty and femininity of women’s clothing hold high value in society since time immemorial. So much so that they were barred from wearing pants, essentially worn by men. In history, in some parts of the world, strict laws were imposed on them for wearing a simple pair of trousers and they had to even take permission to “dress as men”. There are archaic records of women wearing different variations of this garment, like the painted pottery from ancient Greece tells the tale of fierce warrior women, the unisex clothing from ancient China and Turkey and of course, our very own ‘Salwar-Kameez’, that has become the traditional attire for several women in northern Indian states.

The century-old middle-eastern outfits defied gender norms. Turkish Muslim women in ‘pantaloons’ had a huge influence on the upper-class women of the West. Their attire inspired the women’s rights activists to ditch the traditional petticoats and wear the “Bloomers”: loosely fitted pants under a knee-length skirt. The Bloomers became an important part of the Feminist Movement of the 19th century.

Denying them the right to wear pants was just another form of societal oppression of women. Pants and trousers were considered practical wear for working men. As the sole breadwinner of the family, everything fell under their dominion. Hence, pants held power in society; a garment entitled to men. But this piece of clothing gave women the freedom to move freely and take part in activities. But they were expected to be subservient. As women started to become more assertive of their rights, their fight for rebellious fashion soon became a part of the Feminist movement. And even though they had been wearing pants since the two World Wars, society didn’t fail to criticise, humiliate and harass them for putting on a pair!

Also read: Sacred And Sinful: The Moral Policing Of Female Sexuality In Indian Households

Caste-class politics of moral policing of women

The history of the functionality of clothing in womenswear, such as pants and even pockets, is about politics, social diktats, women’s oppression and finally a long fight to independence. The societal rejection of trousers and pants as part of women’s attire is directly related to their social position of being denied financial and property rights.

It is vital to understand the sociological reasoning behind Neha’s incident. Class and caste play a major role in violence and hate crimes against women in India. Women’s road to triumphing the fashion of pants wasn’t easy. Now, pants (with pockets) represent power, independence and freedom for many women but yet to be so for the marginalised, especially the women who are doubly marginalised by the intersection of gender with caste, class and/or religion. Neha was killed simply for making the same choice of clothing the urban elites make daily. Here lies the socio-economic difference.

In the last couple of years, India has witnessed the worst cases of ‘honour killings‘. For centuries, women and their bodies and clothes have been constantly regulated and subjected to surveillance. The onus lies on them to maintain the ‘izzat’ or honour of the family, community and the nation. They are shamed and ridiculed for wearing clothes, deemed to be un-‘sanskari’ in society, having friends of the opposite sex and acquiring any form of ‘modernity’ is seen as the enemy of the traditional ethos. The roots of such heinous crime lie in misogyny, inequality and prejudice against women, and society’s caste hierarchy.

Most of such sacrifices have been for failing to preserve the honour by marrying outside their caste or religion. We cannot be ignorant of the caste difference in society that persists to this day. Women from oppressed caste communities live under severe restrictions by their family patriarchs and are killed otherwise, as seen in this case. These marginalised women are often victims of sexual violence because of being socially and economically disadvantaged. Last year’s Hathras incident and the recent Delhi rape case of a minor girl, reveal how Dalit women are among most oppressed due to Brahminism and caste based sexual violence in India.

Moral policing of women’s clothing presents a serious threat to their lives as is seen in Neha’s case. The autonomy of the female body continues to lie with the larger institutions like society, family and nation.

Such crimes against women are why we need progressive socio-political movements. Moral policing of women’s clothing presents a serious threat to their lives as is seen in Neha’s case. The autonomy of the female body continues to lie with the larger institutions like society, family and nation. They are shamed for their choices and projected as ‘dishonoured’ for bringing shame to society.

Politicians and leaders of our country frequently make sexist and misogynistic comments on women. Society uses rape as an excuse for moral policing on women and their attire and this in turn, promotes rape culture. We need intersectional feminism because women, Dalit women, lower-caste women, rural women are far from being free in this country and the extent of prejudice against them knows no bound. We need the women’s liberation movement like feminism because patriarchy deeply embedded in society continues to dominate and oppress women. Because gender bias, economic deprivation and caste discrimination of women continues to be the norm in patriarchy.

About the author(s)

Rohini Ghosh is an aspiring journalist and a postgraduate Mass Communication student at St. Xavier's University, Kolkata. An intersectional, queer feminist at heart, she is deeply interested in gender and social issues