Trigger Warning: Mentions fatphobia, eating disorders, self-harm, sexual assault

I am a 21 year-old nonbinary fat, assigned female at birth. For as long as I can remember, my body has been subject to agonising amounts of mockery, disgust, and control. As a child, my diet was regulated to the extent that I am unable to understand my body’s hunger cues even today. Most of the food I consumed then was in secret, shameful binges – a habit which snowballed into a lifetime of disordered eating.

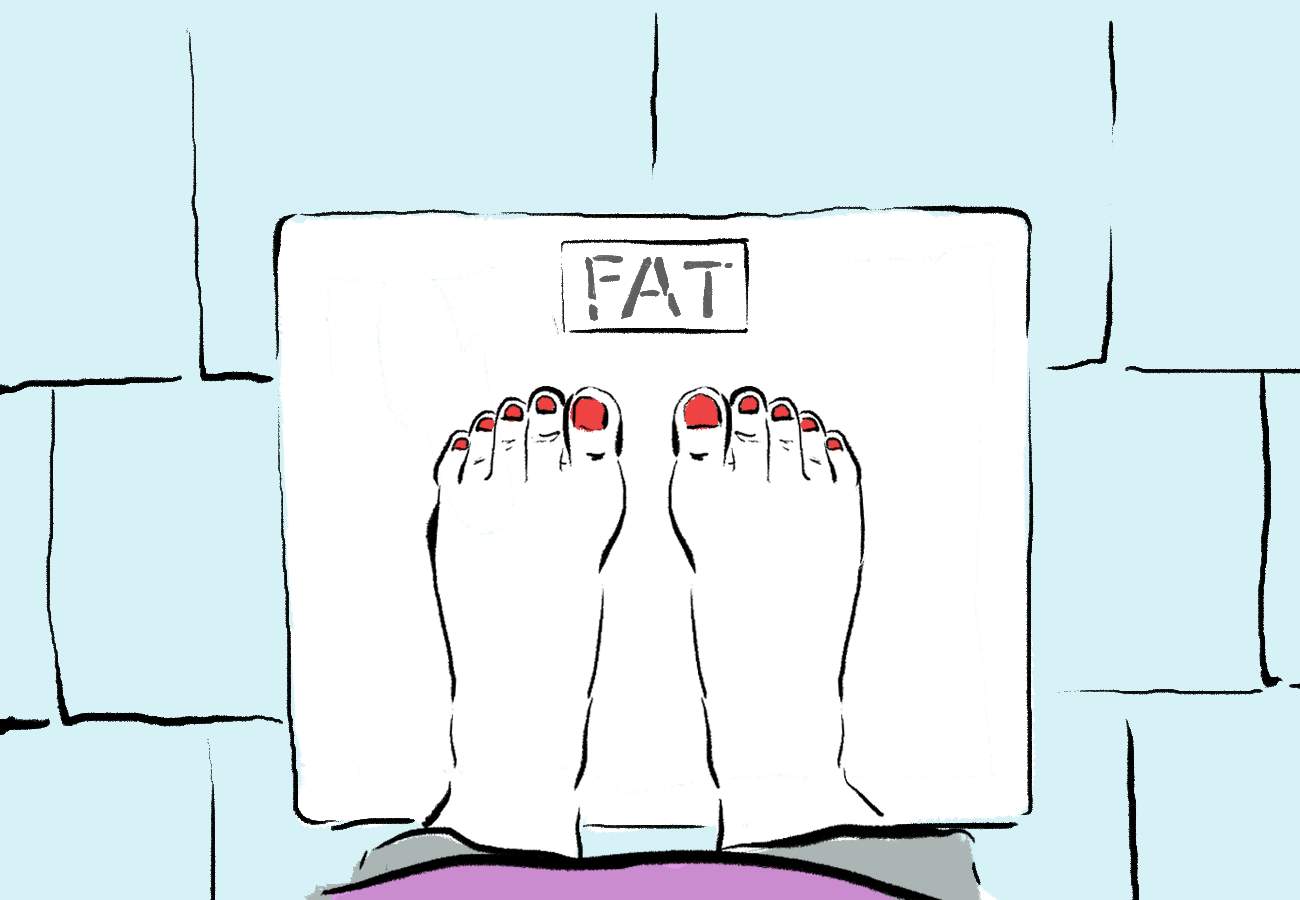

In school, bodies like mine were, quite literally, dehumanised. I was labelled a bhains, a BST bus, or a tank (bullies in army schools can be very context-appropriate). During mandatory medical check-ups, my weight was announced for all my straight-sized classmates to hear and mock, reducing my identity to a number for months after. I remember wishing I got cancer, or some other illness, so that I would lose all the weight and be free of it all.

Diet culture demands that we do whatever it takes, even at the cost of mental and physical harm, to lose the ‘extra’ weight and ‘become healthy’. It is accompanied by a culture of fat-shaming which is ultimately ‘counterproductive’ because it alienates fat people from resources which actually promote healthy weight-loss.

Also read: Post-pandemic Fatphobia At Indian Weddings

Further, diet culture and health metrics, along with the very idea of healthism itself, are rooted in racism and ableism. Nutritionist Kéra Nyemb-Diop, propounds that diets such as Keto are whitewashed and marginalise indigenous foods as unhealthy. At the same time, food items such as oxtails have been gentrified and are sold as “luxury superfoods”. Even the Body Mass Index, which is used as an international marker of good health, was developed exclusively with white, European participants. Audrey Gordon notes that this index was used as a scientific justification for eugenics, and became a standard for evaluating health only after U.S life insurance companies began using weight and height as parameters to determine charges for policyholders.

The diet industrial complex profits off anti-fatness and personal insecurities. Da’Shaun Harrison writes, “….Capital is in teaching people to hate their bodies; how much we value thinner bodies; and how much guilt we associate with foods we enjoy.” Fat Desire – to eat, to lust, to be – is stigmatised as a moral failing, and so, the onus of healthism is shifted from the State and Capital to the individual. Capitalism produces and promotes unhealthy modes of living while simultaneously selling ‘fixes’ for the same; it profits off both and is held accountable for neither; the State does little to provide safe and affordable healthcare. Fat liberation, thus, is necessarily abolitionist.

Capitalism produces and promotes unhealthy modes of living while simultaneously selling ‘fixes’ for the same; it profits off both and is held accountable for neither; the State does little to provide safe and affordable healthcare. Fat liberation, thus, is necessarily abolitionist.

Growing up, I remember feeling like every action I performed – eating, running, playing a sport, even studying – was being surveilled by the fleshly gaze of thinner peers who wanted nothing more than to deride me. On the performance of fatness, Stefanie A. Jones writes:

“The (fat) body is, by the force of circumstances, necessarily performing as a fat body. While the fat performer still has the quotidian agency to act in a plethora of ways, the audience’s intentions are so weighty in determining the actual meaning of the performance that the performer’s work is necessarily an enactment of those audience expectations.”

While I constantly felt the weight of this performance, what I did not realise then was that this performance was also a queer one.

Jackie Wykes highlights the parallels between fatness and queerness. Both have been medicalised and pathologised – ‘treatments’ to ‘cure’ these ‘conditions’, such as electroshock therapy for queerness, or more recently, the DentalSlim weight-loss device which locks the jaw shut and restricts users to a liquid diet, are unsubstantiated and body-harming. Both queerness and fatness have been stigmatised as unnatural and excessive; both are considered as moral crises which must be eliminated. The result – fat, [and] queer bodies are marginalised and labelled as physically and morally ‘unfit’.

Both queerness and fatness have been stigmatised as unnatural and excessive; both are considered as moral crises which must be eliminated. The result – fat, [and] queer bodies are marginalised and labelled as physically and morally ‘unfit’.

Fat bodies are sites of desexualisation, deemed unworthy of love in a gender binary understood primarily through desire. I have never been considered ‘attractive’; news of my involvement in romantic or sexual relationships is usually met with surprise that I have ‘managed’ to find someone. Even my experiences of sexual assault have been treated with disbelief by peers. I have forced myself through abusive relationships, given consent even when I am uncomfortable – believing that I would never be able to ‘do better’.

And so, growing up fat and undesirable, for the most part in a heterosexual environment, meant that I felt defeminised and shunned from gender itself; I literally did not ‘fit’ in.

The clothing I could access and feel comfortable in also invariably shaped my gender identity. Most outlets carry limited plus-size stock for women. In my experience, even when plus-size ranges are available, they cater to straight-sized bodies. XL/XXL shirts and hoodies are common, but the same cannot be said about pants. The reason – the XL shirts are not meant for fat individuals, but for straight-sized individuals looking for oversized tops.

Shopping with family has always been a near-harrowing experience, where, in the confines of shameful changing rooms, I have shoved my body into clothes after clothes, all in the smallest size possible, in a fruitless effort to find something, anything that fit. I was never allowed to buy clothes which showed skin – that included shorts and sleeveless tops – because I would not look ‘presentable’. I was told, “Buy clothes which are a little tight for you, that will encourage you to lose weight,” except that never happened and I was left with clothes that did not fit me. I often feel like an imposter in women’s clothes, and so, it is in men’s clothing, which fits my body better, that I have found refuge. The only way I have known how to present my gender, now and before, is fat.

I have also experienced eating disorders for most of my life. Sometimes, I ate no more than 100-200 calories a day; sometimes, I stuffed myself with all the food I could find, only to spend hours beside the toilet attempting to purge as much of it as I could. During these periods, I have hated everything about my body, how it presents, and turned to self-harm. I cannot lie that these experiences did not contribute, in some degree, to the dysphoria I was already experiencing. I say this not with an intent to pathologise dysphoria, but to communicate that my fatness made me feel like I was ‘failing’ gender while simultaneously being coerced into it.

Also read: Fat Shaming: Why I Stopped Running

Fatness may have little or no bearing on gender identity for other fat, gender non-comforming, and trans individuals; I do not write this to undermine their experiences. But, for me, fatness has always been my gender. Identifying as nonbinary has given me some semblance of agency over constructs which have been beyond my control for most of my life, and allowed me to work through the shame I feel towards my own body better. I am grateful to my friends and allies in the LGBTQ+ community; political conversations with them have allowed me to move past my homophobic and fatphobic upbringing and find radical solace in queer identity.

References

1, 2. Queering Fat Embodiment, ed. Cat Pausé, Jackie Wykes, and Samantha Murray.

Nandini Desiraju is a queer writer, and a graduate in English literature. You can find them on Instagram.

The author is grateful for the narratives contained in Fat and Queer: An Anthology of Queer and Trans Bodies and Lives (ed: Bruce Owens Grimm, Miguel M. Morales and Tiff Joshua TJ Ferentini) which inspired them to write about their own experiences.

Featured image source: Nandini Desiraju