Throughout cultures, women have been seen as the flag bearers of families’ honor and respect. Social structures are so constructed that they give complete or partial authority of women’s agency to men. In order to articulate this authority, an array of rules and laws has been put in place to enforce “modest” behavior. Various tools have been deployed to make sure of the same. Religion, which formed the basis of social conduct in ancient and medieval society, was transformed in a way by those in power that it was used as a sanction for oppression. India has a long history of deploying tools such as the practice of Sati, use of veil, denial of educational rights, among others. This article focuses on the veil as a tool for ensuring modest conduct by women in the later Medieval India.

There is a story that narrates how Yunus Khan and Aisan Daulat Begum, parents of Babur, were taken captive by Sheikh Jamal-ud-din Khan. As a reward for capturing, the Sheikh gave away Aisan Daulat Begum to one of his officers. The begum, however, had the officer murdered. When asked why she did that, she informed the Sheikh that ‘I am the wife of Sultan Yunus Khan; Shaikh Jamal gave me to someone else; this is not allowed by Muhammaden law, so I killed the man, and Shaikh Jamal Khan may kill me also if he likes.’ But the sheikh, recognising an indomitable adversary, sent her back with honour to her husband.

Also read: Zaib-un-Nissa: The Gifted Mughal Princess | #IndianWomenInHistory

The important thing to note here is how gracefully the Begum was accepted by her family and what an important role she went on to play in the political and personal lives of Humayun and Akbar as Emperor Mother and Emperor Grandmother. This incident goes to show the stoic and practical view the Mughals took towards women being captured in wars and battles, an overall indication that little care was given to sexual ‘purity’ alone.

Gulbadan Begum’s biographer has observed various instances when women hosted parties in the Royal gardens and went without veils for hunting. This changed rapidly as notions of chastity and modesty came to be associated with women’s righteousness.

Gulbadan Begum’s biographer has observed various instances when women hosted parties in the Royal gardens and went without veils for hunting. This changed rapidly as notions of chastity and modesty came to be associated with women’s righteousness.

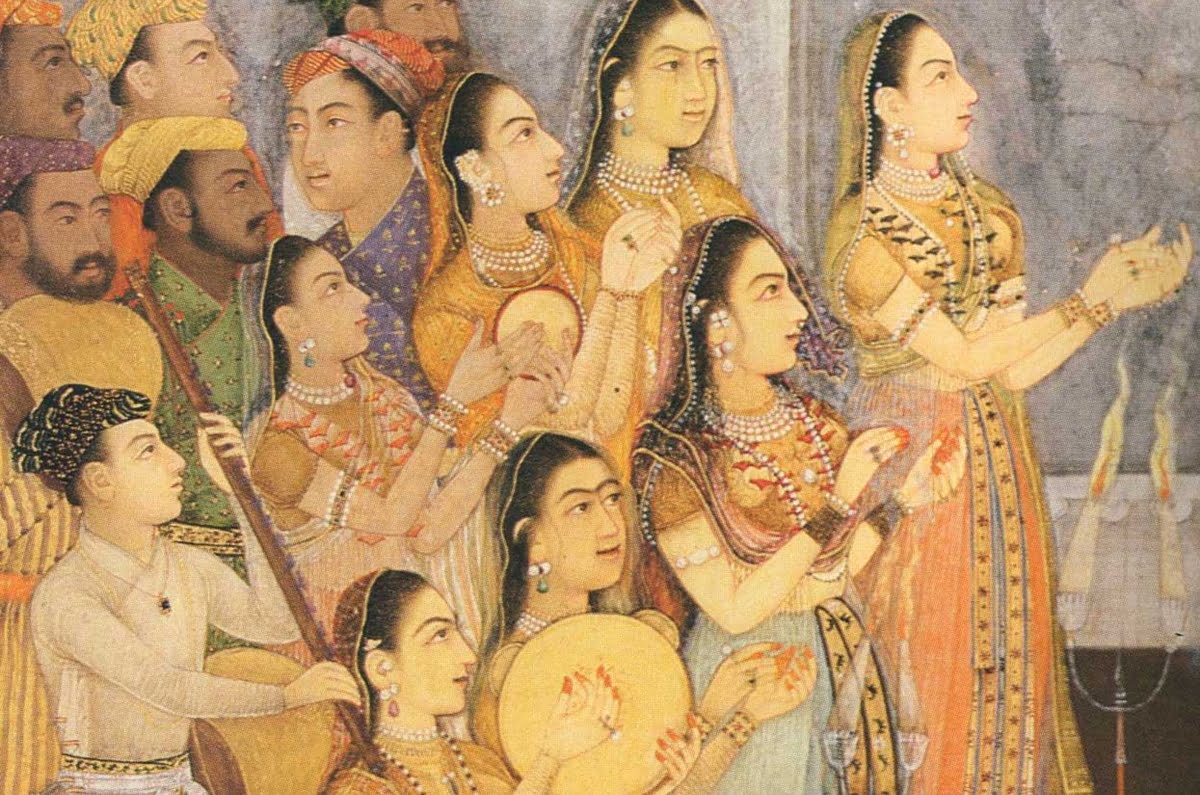

A painting (Figure 1) in the Chester Beatty library shows Holi celebration in the court of Akbar. This gives quite a clear picture of the situation of women’s clothing. Irrespective of their overall attire, which could be a Persian frock with pants or Rajput skirt and blouse, women had their heads covered either in veil or a turban.

As the Mughals got better established as the rulers of Hindustan, Persian rituals and way of living got diluted, especially in regard to how women were viewed. It can be observed that the notions of purity and chastity were adopted by Akbar. The Harem became a formidable fortress and even a glimpse of Royal women became “inaccessible to the sight of man” as is noted by Bernier.

An important thing to be kept in mind is that it was only the individuality of women that was to be concealed. However, the Royal Women as a faceless collective, lived idolized life in terms of beauty and ‘virtue’ was well popularized and known. Paintings and court literature mentioned women only with highest regards, yet more often than not, these paintings and literature were only used as tools to show what a “modest” lady was supposed to look and be like. The question here, then, is not whether women were depicted in paintings and portraits or not but how were they portrayed.

Paintings and court literature mentioned women only with highest regards, yet more often than not, these paintings and literature were only used as tools to show what a “modest” lady was supposed to look and be like. The question here, then, is not whether women were depicted in paintings and portraits or not but how were they portrayed.

Women’s paintings in the Mughal courts were not shy of sexual inclinations either. One can find the image of Gul Safa begum, a woman in the harem of Shah Jahan, whose bosom is relatively open to the gazers. Other paintings also show women in a very sensual posture: in a garden waiting for the tryst with their lovers, often holding the very suggestive narcissus flower, looking at themselves in a mirror with admiration in their eyes, reading a book of poetry, holding a cup of wine. Except for the extremely rare depiction of a royal mother or the Queen herself, the contours of young women’s bodies are revealed to the gaze of the viewer through expensive transparent clothes. More covered depiction of women’s bodies begins much later during, approximately the reign of Akbar II. While paintings cannot be the sole gauge of standards of modesty royal women had to abide by, it is interesting that the painters had the liberty to observe and paint the royal women along their sensuous contours.

On to the Rajput side, it was a different story. It is rare to find portraits of women, royal or otherwise. The painters of the time preferred paintings of women rather than portraits. Even when portraits of royal women were painted, they were based on inscriptions rather than facial features to denote individuality: so strict were the rules of purdah system and the will to curtail women’s individuality in the Rajasthani region that a seventeenth century painting from Isarda has its heroine described as “humara padsah ki 5” or “our King’s no. 5”.

While Abu’l Fazl and Badauni did not confer on a range of issues and accounts, a common narrative in both their account of Akbar’s rule is how women, who were found inadequately veiled in the markets, were considered to have a lewd character were put in shaitanpura on the outskirts of Fatehpur Sikri. This shows two things. One, that the agents of the Empire reserved the right to govern the modesty of women. While one can find various instances where Akbar respected position of women and tried to get rid of systems such as Sati, encouraged monogamy and education for all, it is interesting to note how the dress code of ordinary women was something that even a ‘liberal’ emperor like Akbar did not offer any concession on.

Also read: Begum Samru: Nautch Girl Turned Queen Of Sardhana | #IndianWomenInHistory

While one can find various instances where Akbar respected position of women and tried to get rid of systems such as Sati, encouraged monogamy and education for all, it is interesting to note how the dress code of ordinary women was something that even a ‘liberal’ emperor like Akbar did not offer any concession on.

Secondly, that there was a direct connection between uncovered heads and the perception of their characters, for they were not fined or presented before the court but were sent right off to shaitanpura. That there were laws governing behavior of men at the brothels is a separate topic.

While there was observable difference in the notion of modesty in the early stages of Mughal rule, this soon changed and a stance more agreeable to the Rajputs was adopted. Even though the early writers and rulers scorn and make fun of Rajput traditions such as Jauhar, later on they had a sense of reverence towards it.

Thus, the Emperor assumed the role of protector of the modesty of women. In his family, Akbar employed stricter oversight of the Harem; Abu’l Fazl was under instructions to not mention the real name of Harka Bai in Ain I Akbari and that she was only to be referred to as Maryam Uz Zamani. For the common women, he made covering head virtually compulsory too. Therefore, the veil performed, as it still does, two functions: firstly it became a tool of depersonalisation of a woman’s individual identity and secondly, it “protected” her from the male gaze. It is then easy to observe the flow of rules of modesty. It makes one wonder what impact would being sent to Shaitanpura would have on the woman and her family.

So as notions of modesty spread from the Rajput Rajas to Mughal Emperors, what happened to the ordinary women? One aspect of this question has been covered earlier. The other aspect lies in the hypothesis proposed by historian Rekha Mishra that the common people tried to imitate the Mughal rulers. It is thus proposed that women of the “high class family of both the communities” adopted purdah practice “under stress of their circumstances” since “naturally in a foreign country like India there was greater stress upon it”. Having said that, it is essential to note that strict purdah practices had been observed and enforced by Mughals after the percolation of Rajput traditions and that the primary accounts which are used to substantiate the aforementioned proposal are all from post Akbar era.

However, if the proposal of imitation was to hold any substance, it would be easy to then observe the flow of rules of modesty: the notion of controlling women’s individuality was adopted by the Rajputs which later percolated into the Mughal traditions. These strict rules regarding invisibility of women were imitated by the common people.

Vaani is a History enthusiast, pursuing graduation in the subject from Delhi University. She is passionate about the Feminist movement and likes to read and write about the same. Through her writings, she wishes to make feminism more understandable and acceptable for all. You can find her on Instagram.

Featured image source: Mojarto

A very well researched and articulated article by an amazing author! All the best for the future endeavours!

Loved the piece! A must read for all!

Absolutely loved the piece!

A must read for all the people! Very informative!