The recent conversations around body positivity, body exposure and criticism of fat shaming have spread the message of embracing one’s body as it is, – curves, scars, all of it. We strive to put an end to fat-shaming, both implicit and explicit. While we do this, we somehow don’t consider skinny shaming as a problematic attitude. It is considered as a way of expressing affection and concern towards the recipient.

In conventional Bengali middle class culture, a woman is supposed to have curves, long hair, and a full face to be considered beautiful. Family get-togethers, meetings and occasional visits are dominated by critiques and comments around one’s appearance if there is a change in their body weight or usual physique. The most frequently used phrases in case of weight loss or fat loss are “Hey, what happened? You are getting skeletal”, “Are your parents starving you?”, “Your health is worsening day by day”, and the like.

Whereas in case of weight gain, the topic is either politely avoided or the phrases vary from “Your health has improved”, to “You are looking good”, especially amongst the older kin and acquaintances. While the practice is apparently meant to encourage people “to eat and live without a care”, it often leaves an implicit and subtle negative impact on people with naturally skinny bodies or those like me, who decide to change their lifestyle and dietary practices as part of a journey to become more active. Skinny shaming acts as a way to discourage people with a certain body type from embracing their body as beautiful and undermines the choice of those embarking on their own journey of self-love and self-care.

Born with a primarily mesomorph body type and grown up with a penchant for unhealthy foods and sedentary lifestyle, I have always bordered on the line between ‘healthy’ and ‘slightly overweight’ until my mid-teenage years. For those of you not acquainted with the jargon, the mesomorph body type has the ability to gain and lose both fat and muscle quickly and easily.

Even though I was privileged enough never to have experienced explicit fat shaming, my self-consciousness around my body sprouted with the “advices” and “instructions” from my mother and older female relatives to buy and tailor only loose-fitting clothes, as well as Indian clothes instead of Western ones and to religiously wear the “right bra while going out and when men are around”. In my late teenage years, I decided to give weight loss a try by starting a vigorous exercise routine and altered dietary practices after being advised by a doctor to lead a more active lifestyle.

The cultural ideals around our body image have become so ingrained that they get precedence over other issues like physical health, hygiene and mental well-being, which are relegated to the back corner. Instead of asking about someone’s own choices and opinions about his/her/their own body, more often than not, the issues around weight are talked about with judgment and unsolicited personal opinions which have an adverse effect on the mental health and self-confidence of the recipient are dolled out

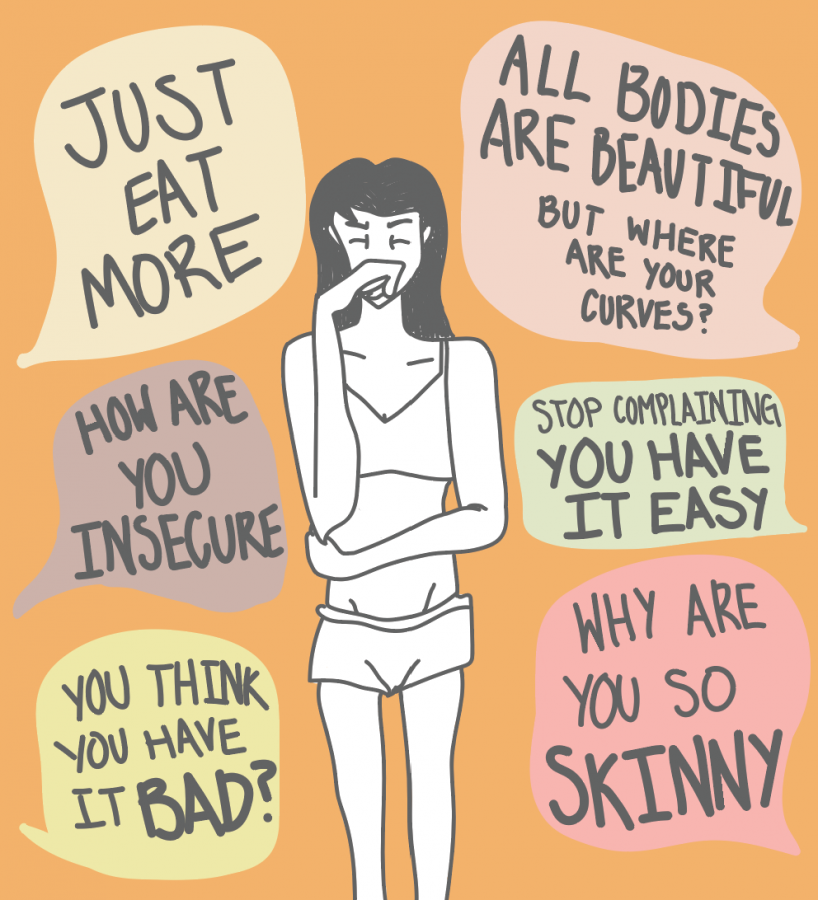

The earliest phase of my immediate and severe weight loss was accompanied by lots of negative comments, chastising, taunts and bullying because of my “skin colour getting darker”, or my “face looking gloomy and ugly”, my “limbs looking masculine instead of feminine”, my “attempt of pursuing modelling and acting” by getting a “zero figure” causing “the loss of womanly charms”, and so on.

However, I moved to a hostel for academic purposes and I gained lots of unhealthy weight then. After returning home my friends, relatives and acquaintances either surreptitiously avoided the topic of body weight or slipped it in between conversations. In reply to my concern about a potential ovarian cyst, or menstrual problems because of weight gain, and the doctor’s advice to lose weight, I received comments on how I looked “womanly instead of skeletal for a change” or how my skin has become “fairer because of better health”.

Also read: A Case For Body-Neutrality Based On A Survey Of People’s Journeys With Their Bodies

The explicit and implicit forms of skinny shaming may not always be intentional and deliberate. Sometimes, they spring up because of genuine concern about health, but most other times, they emerge from adherence to cultural standards of conventional beauty and a negative attitude towards the people who don’t confirm to these standards.

Often, they are generated because of insecurity of one’s own body, where the person, instead of taking positive steps towards self-care and unconditional self-acceptance decides to hinder the choices and decisions taken by other people towards a body which would make them more productive, confident and self-empowered.

Since our cultural concepts of beauty and strict parameters of an ‘ideal body’ mostly revolve around women, they receive these ‘comments’, ‘advices’ and ‘suggestions’ more frequently than men. Yet in my experience, women also happen to be talking about their own and others women’s bodies more than men. The gendered cultural construction of beauty and the aesthetics and expectations from women to adhere to the parameters arbitrated by their immediate socio-cultural environment are to be blamed for this

Even though I saw some of my friends skinny shaming others, I never considered it problematic and a form of bullying at that time and can remember myself participating in it on a few occasions. One of my naturally thin friends once talked about her relatives continuously hounding her and her parents to take her to a doctor to check if she had some medical illness.

The cultural ideals around our body image have become so ingrained that they get precedence over other issues like physical health, hygiene and mental well-being, which are relegated to the back corner. Instead of asking about someone’s own choices and opinions about his/her/their own body, more often than not, the issues around weight are talked about with judgment and unsolicited personal opinions which have an adverse effect on the mental health and self-confidence of the recipient are doled out.

Since our cultural concepts of beauty and strict parameters of an ‘ideal body’ mostly revolve around women, they receive these ‘comments’, ‘advices’ and ‘suggestions’ more frequently than men. Yet in my experience, women also happen to be talking about their own and other women’s bodies more than men. The gendered cultural construction of beauty and the aesthetics and expectations from women to adhere to the parameters arbitrated by their immediate socio-cultural environment are to be blamed for this.

The practice of skinny shaming and the failure to recognise it as something problematic and toxic just like fat shaming is both detrimental to self-love and self-empowerment.

Even though my journey towards unconditional acceptance of my body is far from complete, I have learned to love my body and shrug off unflattering comments even if made by my loved ones. To all my readers, I urge you to think about how you express your concern over the body and appearance of someone else, whether your choice of words and phrases do them more harm than good. Also, I urge you to look at your own body without the mediation of conventionally established parameters of beauty, aesthetics and social acceptability.

Also read: Post-pandemic Fatphobia At Indian Weddings

Evia Ballav is a postgraduate History student at Jawaharlal Nehru University and an aspiring feminist scholar. She is currently not active on social media, but can be reached at eviaballav1@gmail.com