Trigger warning: Child abuse, sexual abuse

My school summer holidays came alive only for the weeks when our cousins visited, mainly for the reason that my sisters are a few too many years older than me that I was yet to qualify for inclusion in girls’ talk. I craved spending time with my cousins who were closer to my age. They also knew play and joy a lot better than I did. Or at least that was how I perceived it then what I now consider to be the dysfunctional, dissociating, abused child I was, had to be hypervigilant, invisible and pleasing in order to cope and survive in an environment controlled by primary caretakers with narcissistic personality disorder.

My cousins respected the boundaries that I hadn’t yet known I was deserving of, excitedly shared their stories, eagerly listened to mine and organised fun activities that my caretakers seemed to approve of. Feeling seen by them for those weeks not only humanised parts of me but also disclosed to me a glimpse of my self-worth by validating my reality. I looked forward to their visit during school holidays so I could take a break from the dissociation and be a child again. I would insist on having them stay longer and I did not want the days to end. Counting down our time together, we stayed up every night and talked until we fell asleep in our shared bed so we could wake up and start talking again.

Who enables whom?

It was one of those nights when we fell asleep tired after a train of loud laughters that I woke up to a hand moving on my body..caressing my hips. I froze with shock for a few seconds and pretended to sleep until I could think of what I could do to make it stop. I jumped up from bed and called his name. He immediately turned sides and pulled the blanket over his head. I went to the living room and laid on the sofa with my eyes wide open, awake and alert. I was riddled with confusion, anger, pain and a myriad of emotions that I couldn’t name or process at the time. I wondered if I should talk to him in the morning and then I worried he would deny it. What would I do if I’m asked to prove it? Why do I feel so powerless, defenseless and isolated? It was perhaps the abused child in me who was already wired to normalise abuse in the face of gaslighting abusers who deny reality.

The sun eventually rose and I waited in the kitchen as each family member woke up and came in for their morning tea. He stayed in bed as long as he could and then I found out that he had said he felt feverish and had asked his siblings if they could leave that evening. He didn’t face me or engage in conversation with me for the rest of the day. We met several times in the years that followed and never discussed it although I always wondered how he forgave himself without ever taking accountability for his behaviour.

In the meanwhile, I became older and eligible to hang out with the older cousins, my sisters and aunts — all cis-het women. They felt more comfortable including me in their discussions as I advanced from being a girl to becoming a woman. In different smaller groups of cousins and aunts, the longer into the nights we spoke, the more secrets we shared. One common secret was several of these women’s experiences of sexual abuse perpetrated by my uncle, the father of the cousin who gifted me that trauma for life.

Although I didn’t open up to them about my experience, because I still feared if they would believe me, I saw in them the same stigma, shame and fear that lived in me. Like most victims, I drowned myself in self-doubt and self-blame, because the other person who was present in my reality could so easily pretend like it never happened. Marred with the burden of the secret, I eventually shared it with my sister. Confirming my deepest fears, she broke my trust and shared it with my abusive caretaker who used it on multiple occasions to hurt me. As years passed by, I realized that I never got over this betrayal. Not only from my cousin, the perpetrator, but also from my sister and adults who enabled each other’s abuse, collectively with those who failed to offer a safe space.

Why does my uncle feel so confident that the different women in the family that he has abused over the years would never speak to each other or to his wife? How many women outside of the family would have had similar experiences from him? Why did my cousin feel so certain that I will never speak up? Why are men so entitled to presume that their victims are by default sworn to secrecy and why do we prove them right, time after time? Why are we conforming and enabling men to continue abusing women with less and less fear of ever being called out?

The danger in the culture of silence

Why does my uncle feel so confident that the different women in the family that he has abused over the years would never speak to each other or to his wife? How many women outside of the family would have had similar experiences from him? Why did my cousin feel so certain that I will never speak up? Does he know about his father? Does his father know that the apple hasn’t fallen too far from the tree? Does my cousin await consent when he sexually engages with women, now that he’s an adult? Did he share it with his brother? Did he ever reflect on his actions or is he illusioned to think he did no wrong? Why are men so entitled to presume that their victims are by default sworn to secrecy and why do we prove them right, time after time? Why are we conforming and enabling men to continue abusing women with less and less fear of ever being called out? How did we cultivate this confidence in the perpetrators that they aren’t even risking exposure?

We are setting the scene for zero accountability. We are setting up a rape culture for our children that teaches boys that they can sexually abuse someone without ever having to take accountability for it. As they grow up to become men, we reinforce their sense of entitlement. We are teaching girls that they will be blamed and shamed if they were to speak up. As they grow up to become women, we have already planted an imprint of shame in their self-image. We are setting them up to live in the same reality, with worse traumas. As sincerely as I try to imagine anything more cruel, I fail. We are offering boys and men in our family a cloak of armour that shields them from any consequences for their actions while we are preparing our daughters to be silent victims who must shoulder the burden of shame, guilt and fear for what we fail to protect them from. We join society in its mission to scaffold sexual abuse as the inevitable consequence that must be faced simply for being a woman.

We are offering boys and men in our family a cloak of armour that shields them from any consequences for their actions while we are preparing our daughters to be silent victims who must shoulder the burden of shame, guilt and fear for what we fail to protect them from. We join society in its mission to scaffold sexual abuse as the inevitable consequence that must be faced simply for being a woman.

Finding comfort with the discomfort of looking within

Eight years later, when my colleague sexually abused me, I felt the same defenselessness from the miseducation I had in my childhood. 14 years later, when a date violated the physical boundaries that I had clearly communicated, I felt the same powerlessness my brain had learned in my childhood. Unlearning and reimagining a radically different future required me to understand my past differently, apportion the blame justly and relieve myself of the weight I was wrongfully sentenced to bear. We, women, the victims, do the self-work of healing to survive. How about the men, the perpetrators of sexual abuse? Why are they not necessitated to do any work on themselves?

This is not to blame the victims for not speaking up, instead calling for everyone to see the collective responsibility we bear. If the last generation had held men accountable, I believe more parents would have invested in educating their sons instead of warning and blaming their daughters. My cousin would then have not dared to run his fingers on my body, at least not without fearing consequences. I ask myself these questions so my daughters wouldn’t have to.

But well, who am I to speak anyway? I plant myself, a whole 7000 kilometers from my home in Kerala, in Berlin, enrol to study gender and publish an article on FII to break my silence. Who am I to speak anyway?

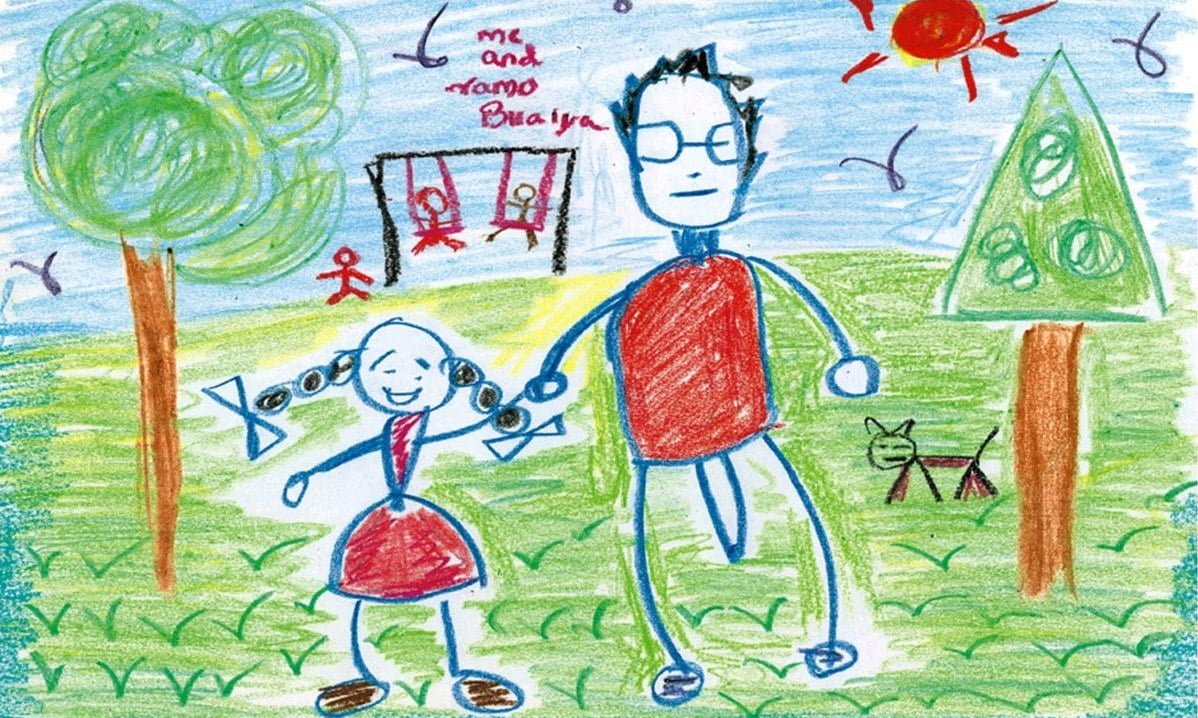

Featured image source: The Palmeira Practice