What vexed me about Netflix’s Bridgerton was not its fetishisation of a Hindu ritual like the haldi ceremony for the delight of White gaze, the mixing of Tamil and ‘Hindustani’ with no explanation for the multilingualism, the mispronouncing and misspelling of ‘Ghalib’ as ‘Ghuleeb’, ‘murali’ as ‘maruli’ nor the colonial amnesiac display of ‘Koh-i-noor’ diamond. What got me bothered was the showcasing of the dowry system and arranged marriage like they are cute but extinct practices from the 1800’s, forgetting how these remain a reality for many communities like mine that were violently colonised by the British. Between 2016 to January 2022, 80 women in Kerala to have lost their lives to dowry disputes, states official records. Meanwhile, we continue to be branded as ‘barbarians’ that need civilising from our noble White masters.

What vexed me about Netflix’s Bridgerton was not its fetishisation of a Hindu ritual like the haldi ceremony for the delight of White gaze, the mixing of Tamil and ‘Hindustani’ with no explanation for the multilingualism, the mispronouncing and misspelling of ‘Ghalib’ as ‘Ghuleeb’, ‘murali’ as ‘maruli’ nor the colonial amnesiac display of ‘Koh-i-noor’ diamond. What got me bothered was the showcasing of the dowry system and arranged marriage like they are cute but extinct practices from the 1800’s, forgetting how these remain a reality for many communities like mine that were violently colonised by the British.

The connection between patriarchy in Ezhava community and the Victorians

I remember feeling a sting while watching Bridgerton season one. At the time, I couldn’t entirely fathom why and how the Regency era women’s lives that Bridgerton portrayed so closely resembled the life I had left behind in Kadakkavoor, a small town in Kerala where I grew up. Growing up, I didn’t understand why my father’s pride rested on his ability to control his wife and tame his daughters. I didn’t understand why the family’s honor was compromised when my sister was seen walking home after university with a boy, unchaperoned. I didn’t understand how that warranted an immediate arranged marriage for the 18 year old girl. I was nine at the time. The days leading up to her wedding, I couldn’t comprehend why the cryptic mentions of sex sounded like something the new bride has to dutifully offer her man after the wedding. Now, I watch it all play out on Bridgerton. Prudence Featherington having to marry Jack Featherington after being spotted together, unchaperoned.. Kate Sharma declaring how her husband’s sexual satisfaction is her duty to meet..

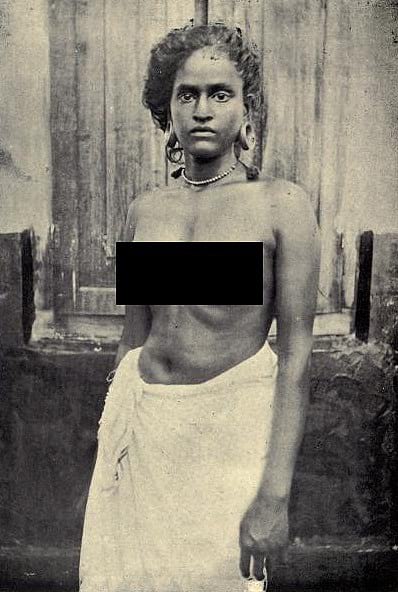

My caste is ‘Ezhava’, one of the ‘polluted’ groups who were deemed untouchable, unseeable and not allowed in proximity to the Savarnas of Kerala, namely the Namboodiri Brahmins and the Nairs. We were toddy-tappers and agricultural labourers. The Channar Ezhava women together with women from Nadar, Paraya, Pulaya and other Avarna and Dalit communities of Kerala organized the Maaru Maraykkal Samaram that started in 1813. Going on until 1859, the revolt became the largest mobilising contributor to the Kerala Reformation movement while the ‘reformer’ status was given away to men, namely, Sree Narayana Guru, V T Bhattathiripad, Chattambi Swamikal, Ayyankali etc. British missionaries offered women the right to cover their breasts if they converted to Christianity. Travancore kingdom collected breast tax from all non-savarna women; after attaining puberty, tax was calculated based on the size and ‘attractiveness’ of their breasts. The story of Nangeli who cut off her breaks in protest and submitted it to the tax collector, leading to the abolition of breast tax in 1859 is one that was only orally passed on until it came to be recorded only recently.

Also read: The Channar Revolt: The Fight For A Dignified Existence

The minimisation of the Ezhava and Dalit women’s significance in the reformation movement on historical records/media/literature and its recent removal from school textbooks following by 19000 schools affiliated to CBSE is a testament to the invisibilisation of the Ezhava and other Subaltern women’s existence and resistance. Until the reformation movement, the Dharmaśāstric tradition of women’s respectability, derived from Manusmriti, was only practiced by Namboodiri women, the Andharjanams and Nair women. According to Ashis Nandy and J.Devika, the British co-opted the reformation movement by making ‘modernity’ desirable. Casteism legitimised their role as the ‘civilizers’ while it also enabled the colonial exploitation of lower-caste population under Kerala’s casteist feudal system.

The Namboodiris and Nairs had been marrying within caste since before British colonialism. However, the Ezhavas, Nadars, Pulayas, Parayas etc. didn’t have such practices of endogamy. It was also common for us to have multiple partners: for both men and women. K.M Sheeba’s studies show how the British promised this facade of ‘women’s emancipation’ and reformer men settled for the caste mobility that came with assimilating the notions of Victorian respectability.

Caste discrimination and poverty of Channar and Nadar women were exploited by Christian missionaries who offered them access to education and health facilities in return for converting to Christianity and/or assimilating into colonial modernity. Ezhava and other lower caste communities adopted the notions of Victorian morality such as chastity, monogamy, patrilocality etc. alongside the utilitarian valorisation of motherhood and ideal womanhood. This, together with the dissolution of feudalism, eventually led to the premature conclusion of caste reformation without the dismantlement of caste hierarchies nor gendered oppression.

As the promise of ‘modernisation’ became further seductive, the Namboodiri Brahmins also started co-opting the reform movement. Muthiringot Bhavatratan Namboodiripad campaigned to overthrow Manusmriti. Marriage reform with Victorian marriage customs and English education for girls became the yardstick for measuring women’s emancipation across castes.

Lord Macaulay, on his ‘civilising mission’, used education as a tool to tame boys into becoming obedient, submissive employees for the British administration. He endorsed mass-schooling for girls as a way to domesticate them with Victorian morality. Ezhavas started by imitating the colonisers for survival but we continue the practices because they’re mistaken as ‘traditions’ we must honor. Lady Violet Bridgerton announces to her children that Miss Sharma will be moving in with the Bridgerton family after the wedding is a practice of patrilocality that now persists in the Ezhava community, which was also one that was learned from the Victorians.

Decolonial theorists point out how heteronormative concepts of ‘providing husbands’ and the ‘rational dutiful housewives’ were introduced in Ezhava communities only by the British. I grew up blaming it entirely on the caste system and Hinduism while in reality, the Namboodiris never really wanted us to imitate respectability prescribed by Manusmriti, fearing the possible dilution of power difference and caste-based hierarchies. ‘Was I so blind?’ Edwina Sharma echoed my feelings. I grew up in Kerala not knowing that arranged marriage, dowry system and other gendered practices that made life a living hell for Ezhava women were infections we caught as a result of the Victorians’ ‘civilising mission’.

Casteism in Bridgerton

Southern parts of India were colonised by the Aryans (the Brahmins) before the British. The caste system introduced by the Aryans assigned themselves with the roles of teachers, historians and priests who decided how we saw ourselves. When the European colonisers arrived, the Brahmins acted as a buffer between Whiteness and us. They enabled the missionaries and assisted in the setting up of British administration. In return, the British colonial law institutionalised caste morality and upheld upper caste privilege.

‘Sharma’ is a common Brahmin surname. Sprinkling a few upper caste Hindu characters on the show is almost like a thank you note from the empire to its enthusiastic allies who loyally sustain the unfinished project of colonialism. Racism is casteist, so is the gimmick of racial representation. One’s caste doesn’t just remain in India when they go abroad. Caste follows. Savarnas’ unearned privileges follow. Caste discrimination follows. Not just from Savarna immigrants but also in the way institutionalised resources and opportunities are available in the global North.

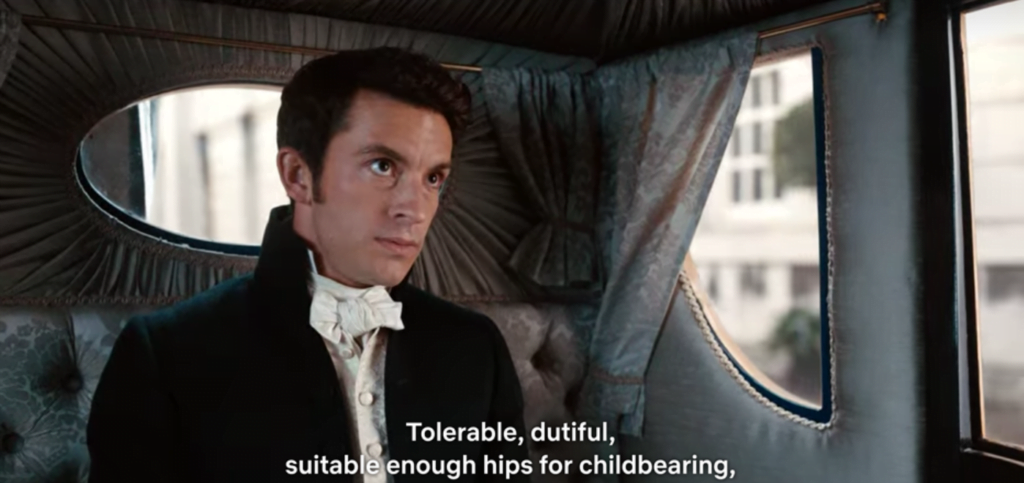

In episode one, there’s a scene of Anthony Bridgerton (played by Jonathan Bailey) sitting in a carriage, listing his expectations for a prospective bride closely resembling the checklist long practised in the Ezhava community. When my mother listed me on a matrimonial website, I felt commoditised. The prospective grooms (or perhaps their parents) use a filter to find women belonging to the same religion, caste and sub-caste with the desirable skin color, hair length, educational background, ‘hobbies’, homemaking skills and body size. The mention of ‘suitable enough hips’ was especially triggering because this is what modernisation wanted us to do in return for the mirage of ‘rescuing’ us from the shackles of the caste system — to breed more Subaltern bodies to do cheap labour. It’s common in Ezhava communities for the groom’s mother to ask the bride to put on weight during the period between the engagement and the wedding, to prove that she can bear his children. I’ve seen so many of my friends stuff their face with food to make sure they don’t disappoint their future mothers-in-law.

It’s common in Ezhava communities for the groom’s mother to ask the bride to put on weight during the period between the engagement and the wedding, to prove that she can bear his children. I’ve seen so many of my friends stuff their face with food to make sure they don’t disappoint their future mothers-in-law.

British colonialism is the reason behind the intergenerational trauma that lives in my body. It’s the reason I had a childhood when I believed that I will have an arranged marriage when I turn 18. It’s the reason I grew up with no imagination of possibilities apart from wife-ing and mothering. My caste, race, gender and class never cease to intersect. When I hear my White British friends and White German friends tell me about their idyllic childhoods and their adulthood with no immigration stress but endless freedom to pursue art or do whatever they want, there’s a part of me that shamefully recognises the resentment that flashes through my heart. I feel enraged each time a White British woman asks me about patriarchy in Kerala with a pitiful but charitable curiosity. They want to know how ‘oppressed’ I was. They want to feel good about their generosity and ease the coloniser’s guilt.

My colonised psyche was excited to watch this aesthetically-pleasing glorification of my oppressor’s sicknesses. I felt my heart racing as I watched the first eight minutes of Bridgerton season two, episode one. I paused because I felt confused. After a few hours, I watched the rest of episode one. The pain I felt was too excruciating, I didn’t want to watch anymore.

Also read: Ezhava And Proud—23 Years After Hiding My Caste From The World

I repeatedly reminded myself that I’m a researcher and the topic of my research is ‘decolonising gender in Kerala’. I’ve spent an uncountable number of hours investigating the colonial roots of Kerala’s patriarchy yet I couldn’t articulate the conflict…nor did I feel qualified to talk about it. It took me time to recognise how the colonial education I grew up with successfully tamed me to become the ideal colonial subject…silent with no critical vocabulary to spell out the injustices. I realised how I needed to watch the whole season in order to be eligible to ‘have’ an opinion…so I did. I sat through the triggers, I allowed the flashbacks, I kept whispering, ‘I forgive myself for watching a show that dehumanises my community‘. I wanted to wait until I could write from a place of love…not when my shoulders tighten, jaws clench and heart races achingly at the thought of the show. Maintaining the stiff upper lip is another Victorian code of discipline. I remembered Audre Lorde’s words about the master’s tools and decided to not tone-police myself anymore. I decided to not be the ideal colonial subject.

I think it’s giving the show too much credit by saying its makers knew “Sharma” is an upper caste name. Mostly likely scenario is they picked one of the most common Indian names they came across. I mean, the Sharmas live in Mumbai, speak Marathi and “Hindustani”, call their parents amma and appa, claim to be impoverished but are always decked out spectacularly. It makes no sense whatsoever lol.

Having said that, a lot of dark-skinned women from South India have resonated with the casting of dark-skinned actresses as romantic leads in a globally popular show like this one. So in that way, yes, representation matters and can have a positive impact, even if the standard is way too low thanks to horrific colorism over the decades in both Indian and Western media.