The idea of the celebration of Diwali or any similar festival is centred around the notions of heteronormativity and celebration of conventional structures – a monogamous couple with children, a heterosexual joint family or similar structures. All these celebrations put up the family as the centre where the sole requirement to feel a sense of belonging is to conform. They are a constant reminder of how these structures and society at large would accept me only if I were to follow their norms and fit in. This is not about reinvention or some replacement for the activities that we do together as a ‘family.’

We put on our fake smiles and fill our Instagram feed with positivity through pretty and wholesome pictures with our family. I have not written this article to invalidate anyone’s joy or happiness that the festival of lights brings for them. I am just flagging how the construction of the festivals we celebrate in the long run is so intrinsically related to the idea of conformity to heteronormativity and belonging with the ‘birth family.’ All of our joys and happiness are to be celebrated regardless of these structures. Instead, these structures are the reason for our happiness and joys. These conventions do not work for many queer people. Still, we tend to participate in them even beyond our wishes because we just have to or face dual exclusion – the one that we feel for not wanting to be a part of it, and the one imposed on us very overtly for our non-participation because it delegitimises our joys.

Also read: Living In Dystopia: A Commentary On Controversies From FabIndia To Dabur Fem

These conventions do not work for many queer people. Still, we tend to participate in them even beyond our wishes because we just have to or face dual exclusion – the one that we feel for not wanting to be a part of it, and the one imposed on us very overtly for our non-participation because it delegitimises our joys.

The Optics of Diwali

Talking about the optics of Diwali, we put up beautiful lights and decorate our homes with earthen lamps, keeping the sanctity intact. All this while, the toxicity stays inside our home, within the four walls. What are all these, if not mere optics? If not mere ways to ‘show’ how our spaces are all clean, cheerful, and bright, announcing it to the whole world. Do you still think it is just about hygiene, positivity, and whose house looks more glamorous or about forming a larger sense of community because we are the same and have the same practices for our festivals – another way of conformation. Our place in society is dictated by ideas of how we participate in its culture – through the ways we celebrate and engage with festivals, which not all of us want to do. These ideas of inclusion that comes with a penalty for not conforming are exclusionary.

Following up more on optics, this is also when our ideas around beauty are shaped by the notions concerning ethnic wear or traditional dresses. There will always be instances of racism or body shaming for any of us who do not fit the standards. These are more or less visible in another exclusionary space – Diwali parties. These gatherings are classist in nature and casteist if you think about who belongs in these spaces and what kind of activities they engage in.

The heteropatriarchal origin and its continuation

The origin of Diwali also has been problematic – while we celebrate Ram, we also need to be cognizant of how Sita was moral policed. A celebration of Diwali also entails participation in the traditions around Diwali, some of which are modern inventions, like bursting crackers. Akin to using Bura na mano Holi hai as an excuse for violating one’s private space and consent, Diwali is also a way to burst some crackers to celebrate or trouble animals, the elderly, children and the unwell, in addition to degrading the environment. And for many, it seems like micro-dosing the environment with pollutants is alright as Instagram aesthetics are more important.

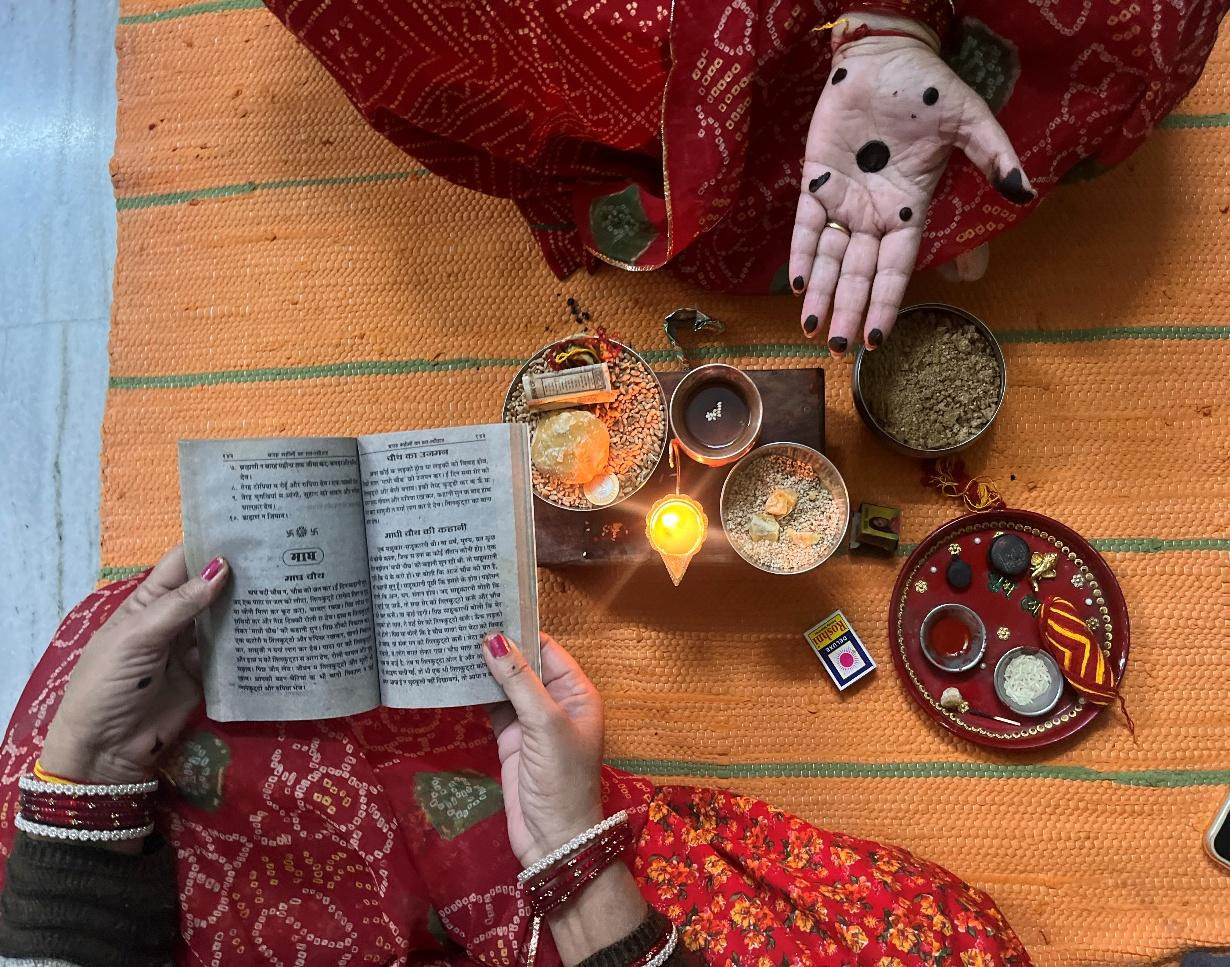

Diwali practices are inherent with gender roles and sexist stereotypes. Girls and women make sweets and the mesmerising rangolis. These images are used to capitalise and sell more stuff. The men, on the other hand, eat, drink, and play cards all night. And no, the mere reversal of these practices in some houses does not account for a welcome change. And no, one advertisement featuring a same-sex couple participating in these rituals is not what ‘emancipation’ means for all of us. We didn’t ask for this, so stop celebrating on our behalf. And no, queer people assimilating into similar patriarchal structures and celebrating these festivals is not the notion of a good life for all of us. It is not the notion of a good, happy, familial life for all of us, especially when we do not have many fundamental rights even.

The dance around good and evil

The idea of the binary of light and dark with all-pervasiveness of patriarchy and ‘birth family’ being the forever place ignores that it is not always a safe space. So many of us have to put up with relatives or extended family members who invalidate our existence, do not respect our identity, or just have been violent towards us. We have to put up with them because “it’s family and it’s a festival.” Or, as a friend told me, “put up a band-aid over years and years of hate and intolerance especially towards women.” As a queer person, I never felt a sense of belongingness during such celebrations where we were expected to forget all the violence we inflict on others. We are expected to dress up and meet toxic people around us to celebrate the festival of lights and keep the evil away. I always wondered if I do not belong with my family, will I be included in this celebration? If I do not want to be a part of such celebrations, will I still be allowed to experience the joy, or will I be sidelined on whatever account?

Also read: In Diwali, It’s Not Just The Crackers Which Are A Problem

The existence of a festival and the compulsion from every structure to participate in the same to feel a sense of belonging or else feel like an ‘outsider’ is extremely problematic. I do not want to spend time building back a structure that broke me and made me feel I don’t belong anywhere until and unless I conform to the norms defined by it.

The existence of a festival and the compulsion from every structure to participate in the same to feel a sense of belonging or else feel like an ‘outsider’ is extremely problematic. I do not want to spend time building back a structure that broke me and made me feel I don’t belong anywhere until and unless I conform to the norms defined by it.

Featured image source: DailyHunt