If you have an eternal curiosity for early Indian history and gender and sexuality, chances are quite high that you have been acquainted with the name of Kamasutra by Vatsyayana and have skimmed through the online available images of Khajuraho and Amaravati sculptures since an early age. Add a group of friends with a similar penchant and your gossiping alternates between ribald jokes and academic jargons around erotic art and literature.

The recorded opinion on sexuality in ancient and medieval India had such a heterogeneous diversity that the written descriptions and prescriptions ranged into opposing and contradicting trajectories. On one hand, we have the smriti (law code) and purana literatures with all the characteristics of a dutiful, loyal, chaste, secluded housewife with repressed sexuality seen as an instrument for procreation; on the other hand we have texts like Kamasutra and Kuttanimata where a variety of sexual practices supposedly considered taboos, like oral and anal sex, masturbation, homosexuality, orgy, voyeurism, exhibitionism, contraception, abortion are discussed without any moral judgement as acknowledged practices. The erotic sculptures, those in the temples and excavated from the cities however are immediately stashed together as something primarily produced as a decorative symbol, or a form of sensual and pornographic entertainment for the male gaze.

Also read: Azizun Nisa: The Courtesan & Strategist Who Played A Crucial Role In The Revolt Of 1857

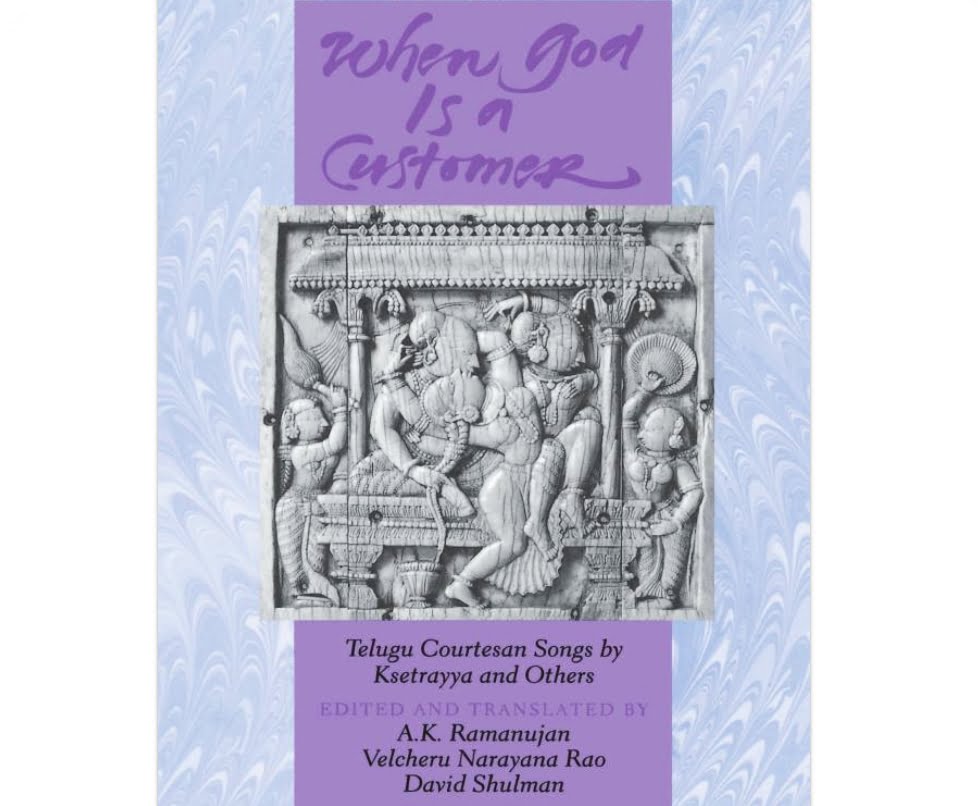

When in a lecture of Memory and Oral Narratives, the professor first introduced the book, When God is a Customer – Telugu Courtesan Songs by Ksetrayya and Others, by A.K. Ramanujan, Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman, I was fascinated with the coarse, irreverent and condescending way the god was addressed by the supposed courtesan and the “unchaste woman”, a category always stigmatised and marginalised throughout history. These padam songs were intended to be sung and danced by the courtesans in the rituals. The book is a compilation of the translated padam poetries composed by 15th-18th century authors from the perspectives of the courtesan, the mistress, the married housewife, the madam of the brothel, the customer and/or the lover, who is the deity, lord Krishna himself, called Venugopala, Muvva Gopala, Konkanesvara and so on.

When in a lecture of Memory and Oral Narratives, the professor first introduced the book, When God is a Customer – Telugu Courtesan Songs by Ksetrayya and Others, by A.K. Ramanujan, Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman, I was fascinated with the coarse, irreverent and condescending way the god was addressed by the supposed courtesan and the “unchaste woman”, a category always stigmatised and marginalised throughout history. These padam songs were intended to be sung and danced by the courtesans in the rituals. The book is a compilation of the translated padam poetries composed by 15th-18th century authors from the perspectives of the courtesan, the mistress, the married housewife, the madam of the brothel, the customer and/or the lover, who is the deity, lord Krishna himself, called Venugopala, Muvva Gopala, Konkanesvara and so on.

In some of them, the woman complaints about her customer or lover, lord Krishna for his infidelity, tricks and lies, insincerity and sharply chastises him; in others, she haughtily refuses or rejects the advances of him because of her pride, or his empty pockets or his tryst with other women. In others, the madam scolds the courtesan, either for being too much infatuated over the looks and sexual expertise of the god and forgetting about the monetary transaction, or for quarrelling with him and turning him away. The god is either a helpless boy with all the money taken by the courtesan or a wandering playboy, moving from one courtesan to another. Some even speak of the courtesan’s or the mistress’s mourning either for the loss of his interest, infatuation over other women and endeavor to win him back or for a separation from him. Some others portray the tryst between the two, when the husband is away or complaint because of too vigorous and rough love-making and possibility of discovering the wounds.

The one thing that shines through all the divergent themes in the poems is the agency and the upper hand of the courtesan that the authors chose to portray in a mercenary transaction purely based on sexual pleasure, where the ultimate assertive voice and proactive role are rendered to those women who were denied dignity and agency. Eventually the intrusion of Victorian morality and the colonial distortion of Indian framework for the economy of desire condemned anything and everything related to courtesans as obscene and morbid. Even though these works were composed as part of Bhakti literature and eventually went through the phase of mandatory de-eroticisation and transformed towards spiritual inclination rather than carnal desire, they were not stripped off their basic essence: coarse yet erotic, and survived the transitions. The vividly picturesque description of lovemaking and eventual orgasm, the possibility of reconciliation after temporary separation, quarrels and obstacles, the mercenary and lustful nature of the interaction all indicate towards the courtesan’s agency.

Also read: ‘Yours Nacheez’—How Tawaifs Left A Void In Cinema: Leaving for Bombay

The pornographic quality of these poems is quite thoroughly recognized. Our professor ended the lecture with the opinion that you could also see them as a proto-pornographic repository of preserved knowledge or rather erotica where the expectations, desires, fantasies of the women were prioritised.

However, my own reading of the poetry collection inevitably draws on its educative nature. The knowledge was produced and passed down by the court poets and devotees of Krishna with the intention of highlighting the interaction between a courtesan and a customer or a woman and her extra-marital lover. The purpose of our knowledge production and preservation is to pass it across generation, time and space to other group of people who may or may not be acquainted with them. Why should the knowledge around sex and sexuality be treated any differently?

The way the court poets described the fantasies, desires, quarrels, regrets and other human emotions associated with women, it can certainly be argued that these were the experiences and expectations of the men on how the courtesans were supposed to behave and deal with certain circumstances. It can certainly be seen as a way of constructing the courtesan culture in a way that would be realistic and might be widely adopted by the courtesans, lovers and mistresses themselves. Alternatively, it can also be seen a means of preserving the knowledge with the intention of passing it to the future generations: those of the playful banter, the priority of mercenary transaction in satiating carnal desire, the subterfuges needed for secret trysts or other reprehensible activities by the women.

The means of education for the courtesans throughout centuries had been the transmission of knowledge within household structure, via mother-daughter, madam-apprentice relationships. But if we look into these padam poetries from an educational perspective, they certainly stand out because of their journey outside the household across a broad cultural and social network with a series of hierarchies in between, intersecting both the royal court and the brothel. Most of the courtesans were well-educated and well-versed in ornate courtly languages, so the dissemination of knowledge certainly does not go outside plausibility. If considered alternatively, these poems could also be seen as a framework to construct the economy of desire amongst the courtly audience, who were presumably urban heterosexual wealthy male population and thus probably constructed the primary clientele for sex workers, mistresses and women having love affairs.

Most of the courtesans were well-educated and well-versed in ornate courtly languages, so the dissemination of knowledge certainly does not go outside plausibility. If considered alternatively, these poems could also be seen as a framework to construct the economy of desire amongst the courtly audience, who were presumably urban heterosexual wealthy male population and thus probably constructed the primary clientele for sex workers, mistresses and women having love affairs.

However, these songs spoke to me not for their elaborate decorum or widely varied themes but for their simple yet realistic and eloquent expressions, the choice of the protagonists and the way they were placed in a reversed model of interaction, thereby altering the positions of vulnerability and control.

Featured image source: cse.iitk