Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for November, 2021 is Popular Culture Narratives. We invite submissions on various aspects of pop culture, throughout this month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

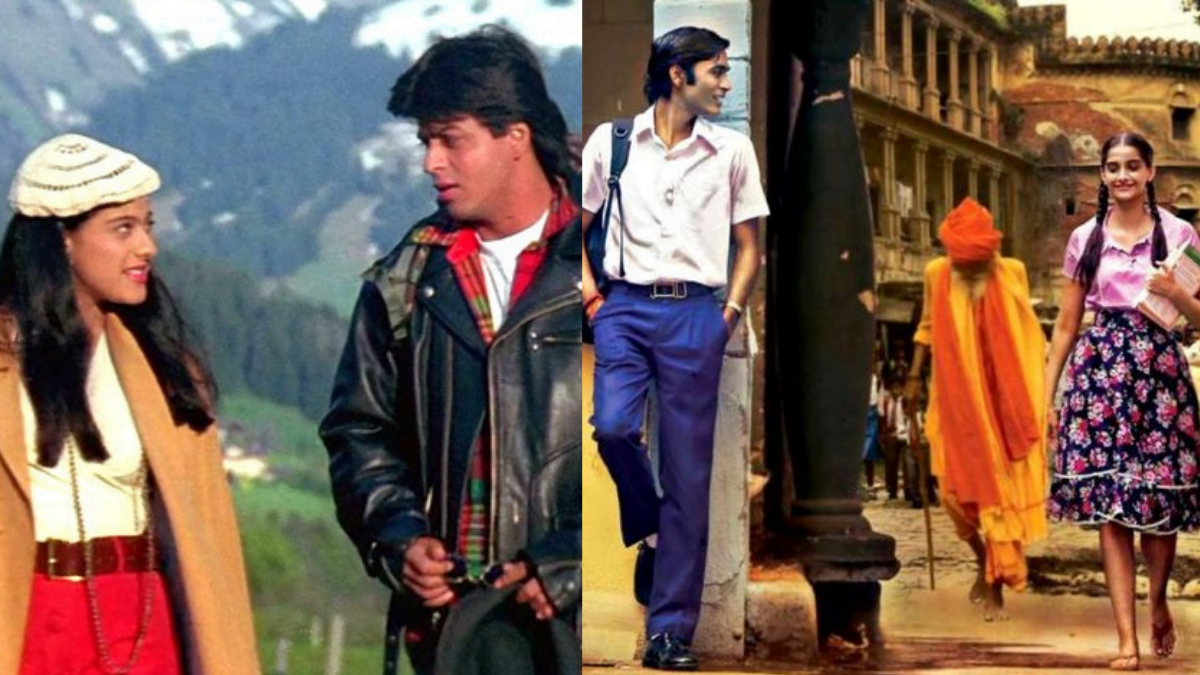

It is a truth universally acknowledged that much of our ideologies are influenced by the content we consume. The movies we watch, the songs we listen to, all mix together in different ways to form our notions of love and romance. But the problem arises when we imbibe the problematic romantic ideas portrayed in Bollywood films. Movies which almost have gained a cult status such as Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995), Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein (2001), Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), Raanjhanaa (2013) and the like are so problematic in their portrayal of love that it become hard to decide where to start while unpacking them.

“Raj, agar yeh tujhse pyaar karti hai toh yeh palat kar dekhegi”, (DDLJ) has been one of the most popular “romantic” Bollywood dialogues ever, to the extent that it is still used weirdly as a form of “consent” in the popular discourse. The given movie, Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, has remained in vogue ever since it came out in 1995. From its mushy romance to its European aesthetics to its evergreen soundtrack, the movie has enjoyed the status of being one of the best and the most romantic films ever.

However, it takes just one unbiased watch to realise how Aditya Chopra has romanticised harassment so well that it comes across as something “cute”. Raj, the typical patriarchal hero, consistently harasses Simran, a ‘cultured Indian’ woman, on a trip to Europe. From the very first scene where they meet, Raj traps her outside the train coach intentionally, pretending that the door is stuck. What follows is the intrusion of her private space and a series of unsolicited, flirtatious comments by Raj. Imagining a stranger doing that to anyone is scary and alarming, but just because the role is portrayed by Shahrukh Khan, the king of romance, it is seen as something which is completely normal and rather funny, or even worse, romantic.

He keeps trying to talk to her creepily even after she clearly says, “Dekhiye, please leave me alone”. In a particular scene, Simran is seen sulking into the corner while Raj keeps clinging onto her until he puts his head in her lap and she struggles to get away from him. Further, in the name of humor, Raj goes on to lie to his friends, “Train pakadne ke liye usey apna haath kya diya, wo toh mujhe apna dil hi de baithi.”

Shortly thereafter, they meet again at a party in Paris, where he follows her while dancing to the iconic song, “Ruk Ja O Dil Deewane”, and even goes on to dance with her forcefully and drops her on the floor in the end. The next day, the romantic hero spills water on her face as a “prank” while apologising for his misbehavior the last night. During the entire trip, Raj intrudes her personal space and somehow, they end up becoming “friends”.

What is perhaps peculiarly interesting is that the hero is pitied for being rejected and appreciated for being a “good guy” just because he doesn’t get physically intimate with her. What follows is a sad sentimental song, where the hero’s pain is exaggerated, and the girl’s trauma remains almost invisible. Even after all this, Reena somehow still chooses Maddy, the guy who wronged her in so many different ways, over her fiancé Rajeev who is actually a kind person and respects her feelings and decisions

Raj plays the role of a “sanskari Hindustani ladka” who would joke about rape but not commit it. Though it is hard to say what was essentially romantic about their meeting apart from Raj’s constant flirtations and Simran’s pushing him away, both characters realise after the trip, that they have fallen in love with each other. The latter part of the movie deals with a patriarchal marriage setup and has random outbursts of toxic masculinity.

Several other movies like Tere Naam and Raanjhanaa employ the ‘chasing’ trope as a natural practice of wooing a woman. The idea is to chase and harass the girl under the aegis of love until she finally gives in and that is seen as a reciprocation of “love” or simply, “consent”. The constant violation of consent and basic protocol of respectable conduct reins heavy in such movies. In Ranjhanaa, Kundan, the obsessive lover, follows the girl Zoya around the city as she goes to school and returns, grabs her hand in public, and takes it as love language when she slaps him saying, “15 thappad khaaye hain, ab toh naam bata do” (You’ve slapped me 15 times, tell me your name at least now).

The hero’s short speech sums up the ideology quite accurately, “Humare UP mein ladkiyaan do tareeke se patai jaati hain, ek toh mehnat se. Subah se shaam peecha karo, prem patra likho or saheli ke haathon pahunchao, par ye toh UP ka har launda kar raha tha, or waise bhi hum kaunsa Shahrukh Khan the jo ye sab kar ke pass ho jaate, so fail ho gaye, ab tha doosra tareeka.” Kundan expresses his views on wooing a woman very clearly.

He could not possibly woo the love of his life, a minor schoolgirl for that matter, by the tactics used by Shahrukh Khan in his top-rated films. So, he decided to go the other way, “…doosra tareeka, ki ladki ko dara do.”, so he threatens the girl that he would harm himself if she refutes his love, and quite ‘heroically‘, stands up to his word. In a mixture of fear and shock, the girl throws her arms around him and kisses him, and that is seen as “consent”. Romantic music plays in the background as the hero’s wish is fulfilled.

Also read: A Stalker Is Not Just An Individual But The Society Itself: How Well Do We Address Stalking?

![Raanjhanaa Subtitles Download [All Languages & Quality]](https://image.tmdb.org/t/p/original/iZbLaQuPNACDXb9xci9VsYnc0uV.jpg)

Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein is another one in the endless list of highly problematic Bollywood movies idealising stalking. Here, (like Ranjhanaa) the hero, Maddy, falls in love at the very sight of the girl, Reena. Maddy’s love is revealed through a series of creepy stalking scenes, including him clicking pictures of her at a friend’s wedding without her knowledge, following her wherever she goes, staring at her from a distance, and more.

He manages to get her phone number from a close friend of hers, of course, through deceit. The concept of consent apparently doesn’t exist in the lives of Hindi cinema characters, as the hero’s father says in a moment of euphoria, “arey, pyaar ho gaya hai toh ladki bhi mil hi jayegi”. The father and son then plot to deceive the gullible girl even after knowing that she is engaged to someone else through an arranged marriage setup (much like Simran in DDLJ). Consequently, Maddy tricks her into thinking that he is her fiancé Rajeev who was to return from the U.S for their marriage.

The problem with these movies is not only that they promote unhealthy and toxic relationships but that they glorify and romanticise them to the point where the audience starts to normalise harassment. In a country where thousands of cases are filed against harassment every year, the consumption of such films certainly cannot be considered ineffectual. Movies wherein obsessive love is romanticised and where the hero would not take “no” for an answer palpably impact the audience’s ideas of love and consent, especially the more impressionable, young minds

In order for his manipulative plan to work, he cuts her phone lines and blatantly lies to her. They then, spend five whole days together while Reena plays the role of a “seedhi-saadhi Hindustaani ladki” (in her own words) as Maddy throws grand gestures, maintaining a fake identity throughout. In the latter half, when Reena gets to know the guy is a fraud, she tells him that she wants nothing to do with him. The hero, of course, is deaf to whatever the woman says. He constantly harasses her, until the day before her marriage.

What is perhaps peculiarly interesting is that the hero is pitied for being rejected and appreciated for being a “good guy” just because he doesn’t get physically intimate with her. What follows is a sad sentimental song, where the hero’s pain is exaggerated, and the girl’s trauma remains almost invisible. Even after all this, Reena somehow still chooses Maddy, the guy who wronged her in so many different ways, over her fiancé Rajeev who is actually a kind person and respects her feelings and decisions.

There are numerous recent films loaded with such problematic tropes like Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (2017), Badrinath ki Dulhaniya (2017), Kabir Singh (2019) etc. All of the movies discussed above (and many more) put forward ideas such as, “ladki ki naa mei bhi haan chhupi hoti hai” (a yes is hiddenwithin the no of every girl), and what the woman says is automatically dismissed.

The problem with these movies is not only that they promote unhealthy and toxic relationships but that they glorify and romanticise them to the point where the audience starts to normalise harassment. In a country where thousands of cases are filed against harassment every year, the consumption of such films certainly cannot be considered ineffectual. Movies wherein obsessive love is romanticised and where the hero would not take “no” for an answer palpably impact the audience’s ideas of love and consent, especially the more impressionable, young minds.

The result is all over news channels throughout the year: rape threats, acid attacks, kidnapping, and much worse. The much popular quote, “everything is fair in love and war” has been taken so literally that the consequences are horrifying to say the least. Bollywood has successfully added to the patriarchal attitude towards women by venerating obsession and harassment. While mass media has the unmatched power to influence its consumers, it’s a pity that Bollywood films choose to rather aggrandise crime and nourish rape culture.

Perhaps, if the censor board paid some more attention to the movies promoting toxicity and misdemeanor, rather than policing bona fide political or sexual expression, Hindi cinema would start being a little less problematic.

Also read: Man Reportedly Shoots Medical Student In Kerala: Can Women Say ‘No’ In Relationships?

Apoorva is currently pursuing her Master’s in English from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. When she’s not re-reading the letters by Virginia Woolf, she likes to try her hand at scribbling poetry. Her areas of interest revolve around Feminist Theory and Absurdist Fiction. She can be found brewing tea at midnight, complaining about our Sisyphean existence

About the author(s)

Apoorva is currently pursuing her Master’s in English from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. When she’s not re-reading the letters by Virginia Woolf, she likes to try her hand at scribbling poetry. Her areas of interest revolve around Feminist Theory and Absurdist Fiction. She can be found brewing tea at midnight, complaining about our Sisyphean existence