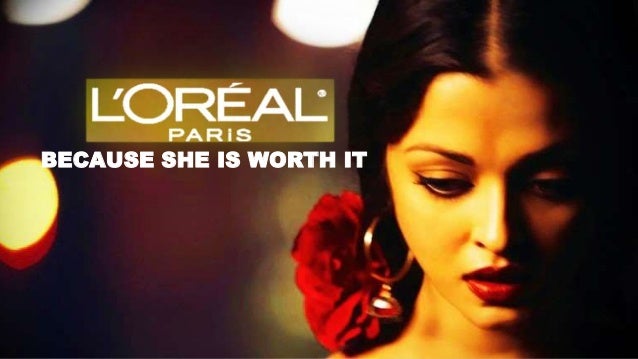

The aesthetics we like and the aesthetics we choose for ourselves are personal choice. However, one cannot deny the role pop culture plays in affecting this choice, specially when we are talking about the in-trend aesthetics of metro cities, popular Instagram accounts, aesthetics of online trends and advertisements. There are multiple advertisements that sell products to “(economically) independent women” under the central message of self-care and space to make choice.

For example, the body hair removal advertisements often portray ‘polished looking’ women of urban setting, bathing in a bubble bath tub, removing her body hair, making a ‘choice’ to remove her body hair. There can be a discussion on how when women start loving and owning their bodies, the capitalist market feeding on these insecurities will fall. This discussion can then extend to how the ‘choice’ these advertisements progressively flaunts is in fact deep-rooted insecurity the women carry from their experiences of early childhood, of dating life, to match the idea of a ‘perfect’ body sold to us by the society. But my concern here is centered around the identities of the women the advertisers think are worth their products of ‘self care’.

While women have a love-hate relationship with their body, in early teenage days, I thought facial hair makes my face look less beautiful. Even after reading about the history of body hair and the sexist origin of Darwin’s theory and after having heard the experiences of multiple women, it took me sometime to be comfortable to reach the point where I would think no less of myself with my facial hair unremoved or non-threaded.

Also read: Miss Universe 2021: Can The Celebration Of Beauty Be Removed From Political Accountability?

The realisation then hit me that many women are aware of the reality of what advertisements do to them but they are still on a journey with themselves to own the physical attribute they have been historically made to feel inferior about. This is not just limited to urban India living in metro cities, the women in rural India too have to go through similar or worse experiences. Women in rural India buy cheaper cosmetics every once in a while and travel to the ‘beauty parlour’ in the nearby city to get their eyebrows shaped.

The realisation then hit me that many women are aware of the reality of what advertisements do to them but they are still on a journey with themselves to own the physical attribute they have been historically made to feel inferior about. This is not just limited to urban India living in metro cities, the women in rural India too have to go through similar or worse experiences. Women in rural India buy cheaper cosmetics every once in a while and travel to the ‘beauty parlour’ in the nearby city to get their eyebrows shaped.

The frequency of these activities might vary based on the age group, status of relationship (married or unmarried), economical status of the family, etc. Recently, in a village called Mangura in Bihar, I met a 26-year-old married woman with two kids, aged three and six. She had gone to the local market after months to buy some cosmetics and her mother-in-law was not very happy about it. The woman had bought a 10rs rubber band which looked like a white flowered ‘jura’, two 10rs nail-paint, and a lip balm of some local company I didn’t know about.

If we were to consider these small acts also as acts of ‘self care’, undertaken under restrictive family conditions and economic bondages of the family, it is disappointing to see no representation of such women in visuals of the advertisements selling ‘self care’ products. When we project the imagery of women of privileged class and caste positions revelling on screen under acts of self care, we invisibilise the rural women toiling in unpaid labour at their homes when we do not give them an advertisement in self care to relate with.

As per the Agricultural Ministry of Bihar, 77% of workforce is involved in agriculture and Bihar’s agriculture industry employs 85% women. Most of these women are either part of the families who hold small farmlands or are labourers. These women mostly either belong to the OBC or to the Dalit community. In the initial weeks of December, many such women can be seen making bundles of rice stalks, arranging them in the fields, making ‘punj’ to store them and are involved in process of having rice seeds plucked from the stalks.

The process demands physical labour which includes standing by the burning ‘chulhas’ for hours. In this process, many women lose their body hair because of exposure to severe heat and rubbing against rough surfaces. Many of these women develop cracks in their feet due to working on farmlands with their bare feet for days. As per National Rural Health Mission report in the year 2012, 68.2% women were malnourished. Many women who work in the farms and contribute largely to the economy of the family have no access to the conventional forms of self care. For them, self care would mean factors such as a balanced diet, good education, menstrual hygiene, etc. At the same time, self care can also be doing every day small acts, such as the woman I met in ‘Mangura’ who took a day off from household chores to go to the ‘bazaar’.

Such small acts of self care interest young women who have only a little access to the Internet, either via the husband’s phone or someone else’s in the family. Some of them have access and leisure to consume television content and are aware of self care advertisements broadcasted on the television. Considering the visual portrayal of beauty in these advertisements, these women fail to see themselves as ‘polished aesthetics’. They do not see themselves fitting into the on-screen representation of women who seem to deserve ‘self care’.

Considering the visual portrayal of beauty in these advertisements, these women fail to see themselves as ‘polished aesthetics’. They do not see themselves fitting into the on-screen representation of women who seem to deserve ‘self care’.

Clearly, for the advertisers, this section of women do not have a girlboss appeal and subsequently, they slip through the gaps in the discourse on self care catered to the ‘mainstream’ audience. Interestingly, rural women in rural settings are represented in family planning advertisements, which may be presumptuous of how rural India’s “lack of awareness” is the result of the population growth in our country.

Also read: Navigating Infantalisation, Non-Disabled Beauty Standards & The In-Between

Has the advertisement industry accepted the fact that the products that they sell will only ‘care’ for a particular class of women living in a particular geographical location? Why do the advertisers, a section that greatly influences popular narratives and norms, want one section of women to feel empowered and deserving in their self care choices, whereas the truth is that only a section of women can afford to buy cosmetic products for themselves. Seemingly progressive taglines of hair removal creams, anti-ageing products, etc. do not mean to speak to the women viewers of diverse identities.

The idea of self care sold by advertisements in pop culture is not inclusive. They do not speak to women collectively about autonomy that women have long been denied but see them only as passive customers.

Born in Bihar. Currently doing MA in Philosophy from Hindu college, DU. Freelances journalistic stories from gender and social justice lense. National and regional Ladli Media Awardee 2021. In constant existential crisis and search of belongingness. You can find Aishwarya on Instagram.

Featured image source: YouTube