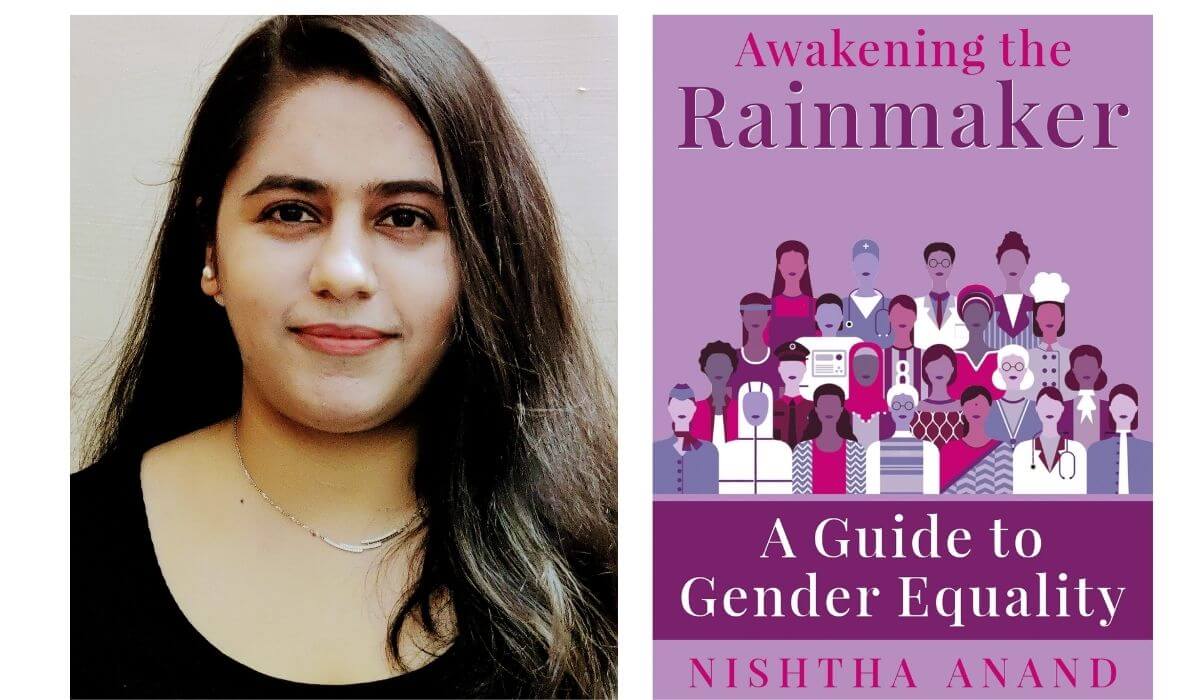

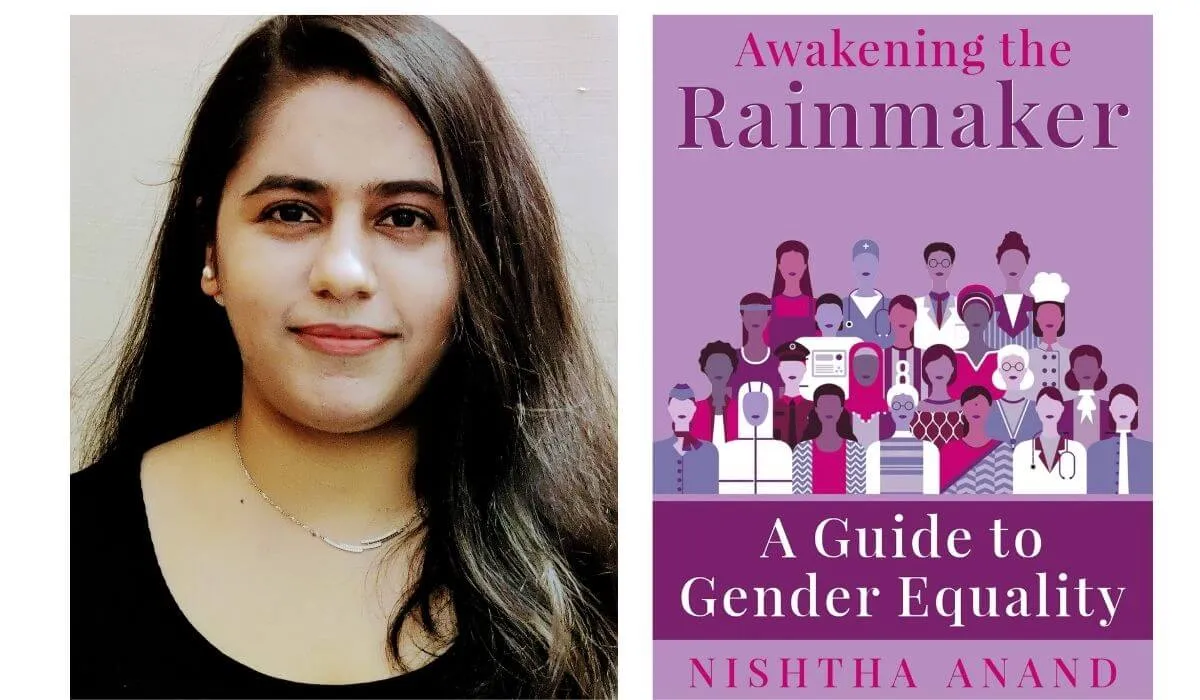

Nishtha Anand’s Awakening the Rainmaker: A Guide to Gender Equality endeavours to support women in actualising their professional goals. Anand foregrounds the significance of gender equality in the workplace and outlines measures for both individuals and organisations to drive positive change.

The book cautiously irrupts into the discourse of biases in upbringing, citing Margaret Mead’s work on culture and childbearing. Mead’s theory of imprinting exhibits the influence of cultural conditioning on people’s personality characteristics. Since the normalisation of conventional gender roles in the popular imagination compels implicit biases in parenting, boys are raised differently than girls. As a result, a majority of young girls grow up to become women who have internalised self-doubt.

Anand rightfully points out that daughters must not “grow up with the notion that every time they achieve something, they have finally matched up to being a son!” Using examples of Anaya and Reema — two women with drastically different professional destinies — Anand emphasises on the importance of assertiveness for women professionals.

The initial chapters in Awakening the Rainmaker begin with a quotation and a flowchart that identify a gendered obstacle and locates its solution. For instance, differences in the attitudes of men and women affect their engagements in the workplace. The solution, Anand posits, is women’s embodiment of assertiveness and inspiration from role models. Though the flowchart can sometimes appear rather simplistic, its format ensures that the chapters adopt a practical approach to address real problems.

The book adopts a diplomatic attitude to opportunities and challenges encountered by homemakers. While it’s commendable for Anand to address the option of a full-time homemaker as a viable choice, it is disheartening to see her neglect the social and cultural factors that deliberately reinforce domesticity as a viable option for women.

Despite, the reason why Awakening the Rainmaker remains limited in its capacity to promote or institutionalise meaningful social change is its premise. ‘Rainmaker’ is an individual who brings in monetary success and productive value on account of their “network and influence.” The social capital that confers on an individual ‘network and influence’ is cultivated by the intersection of different markers of identity, such as class and caste. Social membership is not necessarily an outcome of being assertive and having the freedom to make life decisions

When stakeholders in families tell women that domesticity does not equate submission, they typically present a social expectation in the vocabulary of choice, mimicking the rhetoric of ‘post-feminist’ American films in the 1990s. While domesticity is a perfectly acceptable option if chosen by a woman for her needs and wants, it becomes problematic when it is prescribed by others to help her ‘settle down’ with a husband and kids, which is, more often than not, the case.

More importantly, just as every homemaker is not oppressed, every working professional is not working out of choice and for passion. Women are sometimes compelled to work, often in exploitative conditions, to merely survive.

The book’s second section registers a range of #InclusionStalwart[s] such as Sodexo and Proctor & Gamble. The impact of inclusive policies at the organisational level is imperative for a discussion on the careers of women professionals. Sodexo’s gender-balance study and McKinsey’s ‘Diversity Wins’ study testify to the positive organisational and financial impacts of women leaders. Equally important is Anand’s discussion of peer support, conduct of juniors and reporting managers, and inclusive menstrual leave policies by companies such as Zomato.

Despite, the reason why Awakening the Rainmaker remains limited in its capacity to promote or institutionalise meaningful social change is its premise. ‘Rainmaker’ is an individual who brings in monetary success and productive value on account of their “network and influence.” The social capital that confers on an individual ‘network and influence’ is cultivated by the intersection of different markers of identity, such as class and caste. Social membership is not necessarily an outcome of being assertive and having the freedom to make life decisions.

Further, by ‘awakening’ the rainmaker in women, Anand places the onus of change on women professionals. One of the #RainmakerSpeak sections states that “we [women] cannot blame our past and must take action.” While she empowers her target readers with agency and resilience, she recommends a strategy of ‘awakening’ that functions at the expense of demanding structural change.

It gives the impression that women need to become rainmakers, ignoring that workplace cultures often make it difficult for women to emerge as rainmakers or benefit from women rainmakers.

Also read: In Photos: Women At Work – The Many Facets Of Women’s Labour

Even when Anand details stories from rainmakers and examples of positive policy changes in corporate ecosystems, she neglects the authority of culturally enforced misogyny, which, in an intersectional context, cannot be confronted with simplistic modes of redressal. Her recommendations of De-bias drives and planned exposure to juniors are effective strategies, but they are insufficient in countering misogynistic male homosocial spaces, particularly in leadership roles.

A majority of ‘solutions’ are not practical measures for women professionals. While assertiveness can be embodied or even performed, what can working women do to undo years of patriarchal upbringing? A gender-neutral approach is a relevant social recommendation for families and societies at large, not women. The tools that Anand offers are incapable of bringing about the change that she envisions through her suggestions, primarily because her understandings of work and professional lives are rooted in bourgeois conservatism

In theory, everyone has the potential to be a rainmaker, but the vast majority of examples cited in the book detail life experiences of fairly successful and well known women professionals. While Anand consults rainmakers from a variety of professional backgrounds, most of the rainmakers are not only productive assets for their organisations, but also popular personalities with global recognition. In limiting her pool of rainmakers to extremely successful women, Anand subscribes to mainstream parameters of ‘success.’

Awakening the Rainmaker is a book that largely speaks to young women who aspire to be a part of the top 1 per cent in the future. It exploits feminist vocabulary, but remains grounded in bourgeois ideology that effectively erases women and other non-males who constitute the other 99 per cent. In its discussion on gender inequality, the book rarely transcends the gender binary and fails to acknowledge or address institutionalised exclusion of queer individuals.

Also read: Looking At Women In Work In The Context Of The Squid Game ‘Tug Of War’ Scene

Anand bypasses everyday and broader contexts that are imperative to understand the complex realities of gender inequality in workplaces. She doesn’t speak to women workers, but rather creates women workers who are ideal for the corporate system on behalf of which she speaks.

A majority of ‘solutions’ are not practical measures for women professionals. While assertiveness can be embodied or even performed, what can working women do to undo years of patriarchal upbringing? A gender-neutral approach is a relevant social recommendation for families and societies at large, not women. The tools that Anand offers are incapable of bringing about the change that she envisions through her suggestions, primarily because her understandings of work and professional lives are rooted in bourgeois conservatism.

One of the initial chapters situates common themes in successful women professionals: gender neutral upbringing, an assertive demeanour, an equal marriage, and efficient time management. The final chapter, “Call to Action,” advises women to “just remember” to make choices “with free will.” But, how can women professionals ‘succeed’ if their lives have not been integrated into the aforementioned privileges?

In my understanding, the book is targeted primarily towards women professionals from largely privileged social backdrops. This isn’t necessarily bad, but we have way too many books with superficial understandings of workplace gender inequality.

The economic contribution of Indian women is only 17 per cent of the GDP, which is why a dialogue on women’s successful inclusion and involvement in the workplace needs to be cogently developed. Anand’s book might have the intentions to facilitate this conversation, but it is largely unable to do so.

Featured Image Source: SheThePeople

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a researcher and a writer. Her work lies in the intersection of feminist theory, postcolonial studies, and popular culture.