How many times have we come across a woman’s name as the writer of an Opinion (Op-Ed) piece in a leading newspaper? Not as often as a man’s surely. Is a woman’s opinion worthy in a male-dominated society? Opinion is a loaded term and often used in ‘androcentric’ ways in the sense that a man’s opinion is given more credibility while a woman’s opinion is often dismissed or unheard. In fact, a woman is hardly even granted an opinion. Remember how Meryl Streep called out sexism in a 2011 interview when she remarked, “No one has ever asked an actor, ‘You are playing a strong-minded man’. We assume that men are strong-minded, or have opinions. But a strong-minded woman is a different animal.” Why does that happen? Is an articulate woman, who can speak her mind, considered a threat?

Mind-body dualism

The debate around how the matters of the ‘mind’ are associated with the male and the ‘body’ invariably linked to the woman is not new. And of course, the mind is superior to the body. In this regard, the feminist critique of French philosopher René Descartes’s Cartesian duality is an important intervention. The mind-body dualism has led to gender inequality for privileging the ‘rational’ mind over the ‘irrational’ or emotional body. As pointed out by Nick Butler (2011), “Descartes is held responsible for contriving a patriarchal and phallocentric mode of reasoning that continues to inform management thought and practice in contemporary organisations.” And, mass media is one such organisation.

Women have been subjugated since time immemorial as argued by leading feminists such as Alison M. Jaggar, Sylvia Walby, and Gerda Lerner in their respective works. Women’s voices have been suppressed and their silence has been treated as ‘golden’. What we need to understand and question is the politics behind recognising the domain of intellect as essentially a male prerogative. What are the reasons for the inconsistencies, inadequacies, and discrimination that women have to deal with especially in the space of journalism and media? Where is, or what is the significance of a woman’s opinion in media – the ‘fourth pillar’ of democracy?

Women’s voices have been suppressed and their silence has been treated as ‘golden’. What we need to understand and question is the politics behind recognising the domain of intellect as essentially a male prerogative. What are the reasons for the inconsistencies, inadequacies, and discrimination that women have to deal with especially in the space of journalism and media? Where is, or what is the significance of a woman’s opinion in media – the ‘fourth pillar’ of democracy?

Also read: Where Are The Women Poets? Questioning The Canon Of Indian English Poetry

Gender inequality in media

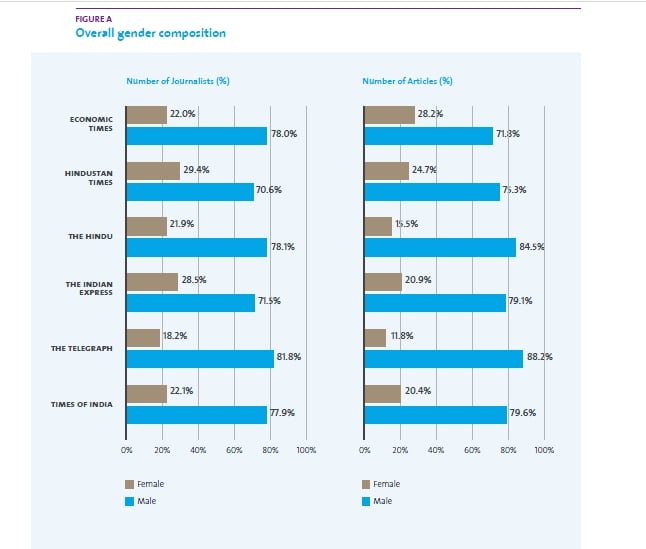

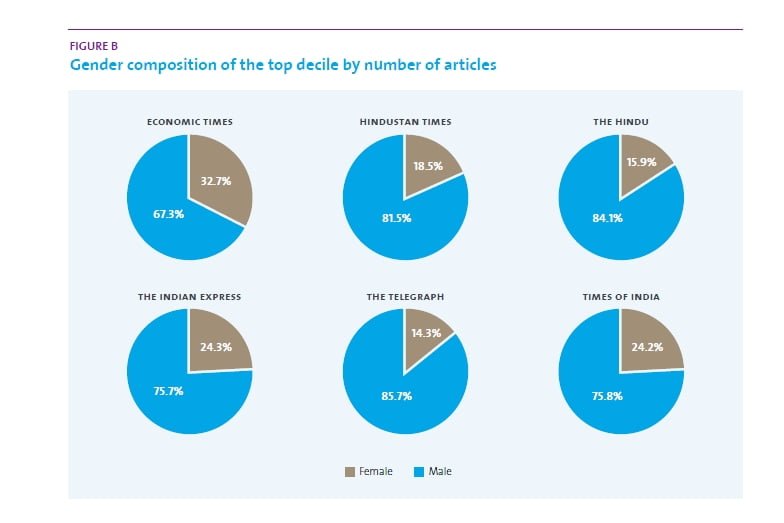

The UN Women’s comprehensive report on the representation of women in the India media titled, ‘Gender Inequality in Indian Media: A Preliminary Analysis’ (2019) is a stark revelation as far as women’s abysmally low representation in mass media is concerned.

As an institution, the press or the news media upholds the principles of objectivity, factual accuracy in reportage, sensitivity, and ethical standards. When we try to investigate the term ‘objectivity’, which finds its footing on codes of impartiality and is divested of biases and prejudices, we also come to learn about the perils of homogenizing lived experiences. Heterogenous realities of communities belonging to different structures of class, caste, gender, and race are often given limited space. Additionally, for the sake of being true to the universal standard of ‘objectivity’, subjectivities and intersubjectivities are denied adequate mention and such an attitude reveals itself to be male-dominated and exclusionary.

If we situate the objectivity-subjectivity discussion within the realm of the Indian media, we will be able to recognise the inherent gender stereotypes and patriarchal norms that dictate the space of ‘free’ press. Across the Front, Opinion, and Business pages of some of the prominent newspapers and dailies, only about a quarter of the articles are credited to women.

Further, given the various beats, be it lifestyle, culture, politics, sports, entertainment, etc., very few women have bylines on stories related to sports, politics, defence and national security. Contrastingly, women bylined over 30% of the articles on culture and entertainment, environment and energy, and public life.

In this regard, Alison Jaggar’s seminal work, Feminist Politics and Human Nature, first published in 1983, becomes essential reading to understand why the code of conduct, morality, ethics, et al differ for men and women. She explains how ‘sexual romanticism’ works towards patriarchal assertion of the ‘uniqueness’ of women, the mystical motherhood experience, and women’s ‘special’ purity. This is what gets replicated in mass media too where women are pushed to report more on what are considered ‘feminine’ subjects, ‘naturally prescribed’ for them.

In The Creation of Patriarchy (1986), pioneering historian and feminist Gerda Lerner highlights how ‘private patriarchy’ is exclusionary and ‘public patriarchy’ is segregationist. Public patriarchy becomes a tool of oppression and women in the workspaces, bureaucracy, and other organisations fall prey to forms of discrimination and gender bias.

As per the 2019 UN Women study, “Of the 17,311 articles analysed, only 457 were on gender issues, or less than 3%. Of all such articles published in The Telegraph and The Hindu, just 17.9% and 24.1%, respectively, were bylined by women. In the other four English newspapers, over half of the articles on gender issues were by women.”

Raewyn Connell, Australia’s renowned sociologist explores the relationship between and dynamics of masculinities and neoliberal globalisation. In her seminal works such as Gender and Power (1987), The Men and the Boys (2000), Masculinities (1995), and others, she discusses ‘hegemonic masculinity’ in a gendered society. She explains, “‘Hegemonic masculinity’ recognizes not only the gendered character of bureaucracies and workplaces as well as educational institutions, including classroom dynamics and patterns of bullying, but also the media, for instance the interplay of sports and war imagery, as well as the virtual monopoly of men in certain forms of crime, including syndicated and white-collar crimes” (Appelrouth and Edles 2015). This hegemonic masculinity pervades in mass media too.

A woman’s standpoint

Within this paradigm, it is essential to examine the notion of standpoint, as explained by Sandra G. Harding, Nancy Hartsock, and Dorothy E. Smith. What is a standpoint? A standpoint is your location from where you articulate your lived experience and what you experience is related to and dependent on the location. As a sociologist, Smith understood how the discipline of sociology was male-centric, which had to be explicitly ‘objective’ and ‘scientific’.

Smith argued that women’s knowledge, their epistemology had no space in the ‘masculine-dominated macrolevel sphere’ and the women, who were part of the public sphere, were obligated to emulate or follow the codes, as sanctioned by patriarchy. Therefore, a woman’s subjectivity, her standpoint, her agency, her voice – everything was absent or rendered meaningless.

Smith’s concept of ‘bifurcation of consciousness’ elaborates this where a woman is compelled to perform according to the male worldview when she is in the public world. There is a split in her personality within the home and the outside world. Further, she argues how social domination perpetuates and operates in institutions, “bureaucracy, administration, management, professional organization, and the mass media”. Smith describes this as ‘relations of ruling’ where women are strategically excluded from positions of power. In the Indian media setup as well, we can see how women rarely occupy the leadership or management roles. The fact that there are not many reporters covering the ‘hard’ beats such as crime, politics, defence and national security reinstate the fact that our society is comfortable situating women in roles that are closer to household duties such as caregiving, cooking, cleaning, etc. Therefore, the category of ‘soft news’ that covers the realms of lifestyle, parenting, fashion is reserved for women. So, even though they are part of the ‘outside’ world of the media and journalistic projects, their domain of reportage is restricted to the tropes of ‘private’ life. This is why, the structures of ruling and institutionalization of power are under patriarchal control.

Also read: The Wife: Exploring Women’s Writing In A Male-Dominated Canon

Problematizing the male gaze

The ‘male gaze’ is another concern which is deeply entrenched in the media. The portrayal of women in cinema, advertisements, on radio, and other platforms reeks of misogyny and gender bias. For instance, as a schoolkid, Meghan Markle was disturbed after watching an advertisement about a utensil cleaner targeted towards women of America. As an 11-year-old, she protested and wrote to Procter & Gamble expressing her resentment against the sexist language used in the TV commercial. Meghan raised a valid question in her letter objecting to the commercial which included the line: “Women all over America are fighting greasy pots and pans.”

She asked, why should there be a generalisation that only women must be engaged in doing the dishes in the kitchen? What about the men, don’t they have any responsibility in running a household? Her concern was heard and the advertisement was revised; it was televised with the voiceover echoing, “People (instead of women) all over America”. This is a small example of how subservient roles are naturally reserved for women without any resistance or inquiry.

The role of media must involve propagating a fair representation of people’s lived experiences and not assume a position of arbitrary power and authority so as to dictate the way of living. That in turn would perpetuate ‘hegemonic masculinity’ which must be questioned and challenged. Commodification and objectification of women in the media are akin to what patriarchy demands of women and if the woman raises her voice and resists, she is immediately vilified and castigated for being ‘transgressive’. However, all is not lost. With films such as Queen, Angry Indian Goddesses, Lipstick Under My Burkha, Pink, and more, the representation of the woman’s character has undergone significant change. The scripts of these films make a conscious effort to not imprison women in the outmoded ‘damsel-in-distress’ narrative, waiting to be ‘rescued’ by their ‘knight in shining armour’. Still, miles to go!

Commodification and objectification of women in the media are akin to what patriarchy demands of women and if the woman raises her voice and resists, she is immediately vilified and castigated for being ‘transgressive’. However, all is not lost. With films such as Queen, Angry Indian Goddesses, Lipstick Under My Burkha, Pink, and more, the representation of the woman’s character has undergone significant change.

The need of the hour is to identify the gender barriers that restrict women’s participation in the workforce, especially media, and alter the dynamics of the ‘gender regime’ that is premised on inequality. Women must strive to rewrite the official narrative, debunk patriarchal norms, and dismantle barriers while addressing inequality and injustice in the public spaces of employment and work.

References

Appelrouth, Scott, and Laura D. Edles. 2015. “Feminist and Gender Theories” (Chapter 7). In Sociological Theory in the Contemporary Era; 3rd edition. SAGE Publications

Butler, Nick. 2011. “Duelling with Dualisms: Descartes, Foucault and the History of Organizational Limits.” Stephen Dunne Centre for Philosophy and Political Economy; University of Leicester School of Management, University of LeicesterSmith, Dorothy E. 2005. Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press

Featured image source: New York Times

About the author(s)

With over 10 years’ experience in publishing and journalism, Ipshita Mitra has a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU and holds a PG Diploma in English Journalism from IIMC. She did her MA in Gender and Development Studies and is currently pursuing her PhD in Gender Studies from IGNOU.

She has worked with The Times of India, The Asian Age, The Quint, Om Books International, World Monuments Fund India Association, and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2016, her short story ‘Cacophony of Silence’ was published by Nikkei Voice, a Canadian-Japanese newspaper. In 2020, her short story ‘Bohemian Sailor of the Gulf’ was published by Sublunary Editions, a Seattle-based independent publisher. The Indian Quarterly (April–June 2021) published her short fiction, ‘Kabuliwala Returns’. She writes on books, culture, environment, and gender for TerraGreen, The Hindu, Scroll.in, The Wire, Wasafiri, Firstpost, Huffington Post, India Currents, and others. She tweets @ipshita77.