“Love has no gender.”

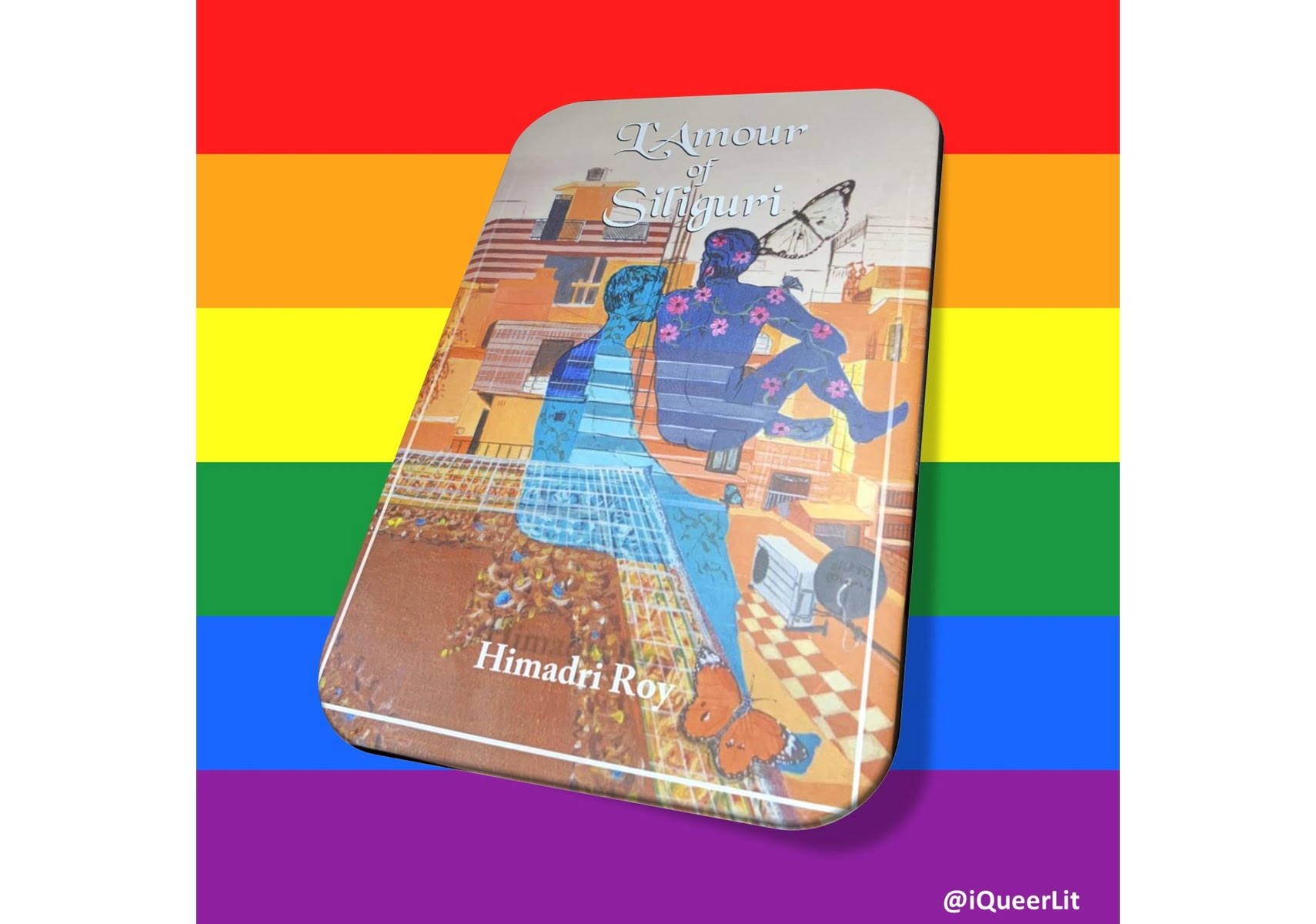

This line, spoken by one of the characters at a crucial juncture when the protagonist has reached the end of his tether, aptly summarizes Professor Himadri Roy’s latest offering, L’Amour of Siliguri (Upanayan Publications). What is so extraordinary about an ordinary dialogue like, “Love has no gender”? If we pause to ponder, we will realise that over the years, legendary romances, fairy tales, dramas, and popular love stories have invariably focused on how their protagonists overcame the barriers of class, caste, colour, religion, ethnicity, age, socio-economic status to seal a happily-ever-after. ‘Love has no age’, ‘Love is beyond geographical boundaries’, ‘Love doesn’t discriminate if you are rich or poor’ are some tall claims we are familiar with and probably accustomed to, but how often do we stumble upon a phrase like, “Love has no gender” in literature? Rarely.

Love Blossoms in Rain-kissed Siliguri

As a ‘modern’ society, we might be warming up to the emancipatory and progressive concepts of intersectionality, gender fluidity, cosmopolitanism, pluralism, regional diversity, and so on. However, on closer scrutiny, it is evident that these revolutionary ideas are restricted within academic discourse. There is more preaching than practising. Acceptance and tolerance are not easy or obvious outcomes when discussions revolve around homosexuality, inter-caste marriages, and same-sex relationships. In a heteronormative society, the rules of the ‘natural’ order compel us to define gender in terms of man-woman/he-she/him-her.

Today, the pronoun ‘they’ is steadily carving a space outside the gender prison of traditional binaries and assigned roles. At the centre of this vortex begins a turbulent love affair between two teenage boys, Advait and Zahran, that threatens to unleash thunderstorms upon the rain-soaked town of Siliguri.

Strength in Vulnerability

A fast-paced narrative interspersed with cliffhangers and tear-jerking episodes, the story (most of which unfolds in flashback) progresses like a screenplay. Prof. Roy, Director, School of Gender and Development Studies, Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), Delhi with a specialization in Queer Studies, Gender and Literature, and Gender and Media among others deftly addresses the contemporary issues of religious fundamentalism, casteism, political fanaticism, regional conflicts, and hegemonic masculinity through the love story of a same-sex Hindu-Muslim couple that is determined to brave all upheavals and adversities, even those leading to fatal consequences. The beauty of Advait and Zahran’s relationship lies in their shared vulnerability which strengthens them to be each other’s protector and saviour. It is them against the world. However, a lot is at stake and romanticising their vulnerability and social powerlessness could be a risky proposition. The reader is aware of the cruel reality that awaits the lovers who are, perhaps, being too ambitious (or naïve).

The beauty of Advait and Zahran’s relationship lies in their shared vulnerability which strengthens them to be each other’s protector and saviour. It is them against the world. However, a lot is at stake and romanticising their vulnerability and social powerlessness could be a risky proposition. The reader is aware of the cruel reality that awaits the lovers who are, perhaps, being too ambitious (or naïve).

Also read: Megha Rao’s ‘Teething’ Is A Kaleidoscope Of Smells, Sights & Silences

Family and Friends Save the Day

Right when the reader loses all hope for the couple making it through without hurt and pain, some promising and heartfelt interventions keep the dying faith alive. Two of these stand out in particular. One of the poignant and powerful scenes is when Advait’s father Mudit, part of the ‘respectable’, ‘dignified’, conservative Dutta family, is enraged to learn of his son’s sexuality. When all hell breaks loose, Advait’s eldest aunt Dola comes to the rescue. She is the voice of sanity who reminds her brother-in-law how he too had married a lower-caste woman years ago because, after all, love triumphs all. She pronounces, love is love, no matter what. Whether it’s caste, class, sexuality, gender, and race, love does not and cannot discriminate. Better sense prevails and there occurs a change of heart as Mudit hugs his son. The second incident that keeps the fire of hope burning is when Advait’s school friends Basabjit and Pinaki extend unconditional friendship to him without hesitance, doubt or interrogation. They help restore Advait’s confidence and assure him that his love for Zahran is pure and soulful, and that it cannot be tarnished or measured by arbitrary dictates of society.

Understanding Hegemonic Masculinity

The engulfing darkness of a homophobic world is ready to crush Advait’s fighting spirit and make him suffer for ‘making the wrong choice’, a phrase that is repeatedly used by Daksh, who is, surprisingly, Advait’s best friend since early school days. Daksh, the self-appointed ‘guardian’ of the ‘emotionally weak’ Advait is not all aggressive from the beginning. He is not homophobic, either but what he cannot come to terms with is the fact that Advait could find a lover in someone other than him.

Daksh belongs to a Marwari family and upholds the ‘unsaid’ rules of society. He is not a pacifist, he is a fundamentalist, something that Advait discovers much later when he begins to realise that Daksh does not approve of his lover’s religious identity. More than his homosexuality, it is Zahran’s religious background that Daksh is unable to reconcile with. Within the hierarchy of masculinities, it is important to understand the relationship between Advait and Daksh through the lens of what Raewyn Connell, Australia’s renowned sociologist, calls ‘hegemonic masculinity’ in her seminal work Gender and Power (1987). Though the phrase ideologically means men’s ‘legitimate’ dominance over women in a patriarchal social order, the argument could be extended to examine the subordinate position of those men too who do not or refuse to conform to gender norms. For instance, Advait is ‘soft-spoken’, ‘harmless’, ‘vulnerable’, and ‘caring’, characteristics that are conventionally considered ‘feminine’. Advait’s homosexuality is an added burden which situates him within the matrix of ‘subordinate masculinity’, something that Daksh tries to ‘save’ his best friend from but fails.

Also read: Sindhu Rajasekaran’s ‘Smashing The Patriarchy’: A Book That Fails To Convince

Love Triumphs

While L’Amour of Siliguri shines through as a compelling story of love and eternal friendship, the editorial involvement is less than satisfactory. Minor syntactical errors and typos that occasionally interrupt the narrative flow could have been easily avoided. Even though the predominant thematic concern deals with the struggles and hardships of same-sex couples in a ‘forward-thinking’ world, the story ends with a promise that come hell or high water, there is always light at the end of the tunnel. This is the most praiseworthy aspect in the novel. At one point, the narrator’s voice echoes, “The monsoon season is always pleasant for people in Siliguri, because the chill wind stays all the time, even if it stops raining.” That is why, even when nothing is working in your favour, the will to survive and conquer must stay all the time and not die without putting up a good fight.

The book is available on Amazon.

Featured image source: Indian Queer Literature/Facebook

About the author(s)

With over 10 years’ experience in publishing and journalism, Ipshita Mitra has a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU and holds a PG Diploma in English Journalism from IIMC. She did her MA in Gender and Development Studies and is currently pursuing her PhD in Gender Studies from IGNOU.

She has worked with The Times of India, The Asian Age, The Quint, Om Books International, World Monuments Fund India Association, and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2016, her short story ‘Cacophony of Silence’ was published by Nikkei Voice, a Canadian-Japanese newspaper. In 2020, her short story ‘Bohemian Sailor of the Gulf’ was published by Sublunary Editions, a Seattle-based independent publisher. The Indian Quarterly (April–June 2021) published her short fiction, ‘Kabuliwala Returns’. She writes on books, culture, environment, and gender for TerraGreen, The Hindu, Scroll.in, The Wire, Wasafiri, Firstpost, Huffington Post, India Currents, and others. She tweets @ipshita77.