“John is a physician and perhaps… that is one reason I do not get well faster.”

At the very beginning, the protagonist of the short story, “The Yellow Wall Paper”, states her disillusionment with medical science and its male practitioners, be it her husband or her brother. They provide her with medicines and prescribe air and exercise, but they also do not really believe that she is sick because she has “no reason to suffer’. They believe she is only suffering from a “temporary nervous depression”. This happens despite her repeatedly mentioning her tiredness and sleeplessness. She also admits that being near her newborn child makes her nervous, which makes one wonder if it could also be a case of postpartum depression.

At the very beginning, the protagonist of the short story, “The Yellow Wall Paper”, states her disillusionment with medical science and its male practitioners, be it her husband or her brother. They provide her with medicines and prescribe air and exercise, but they also do not really believe that she is sick because she has “no reason to suffer’. They believe she is only suffering from a “temporary nervous depression”. This happens despite her repeatedly mentioning her tiredness and sleeplessness. She also admits that being near her newborn child makes her nervous, which makes one wonder if it could also be a case of postpartum depression.

Besides medicinal recommendations, the protagonist also undergoes the “rest cure”, first introduced by the physician Silas Weir Mitchell, which included isolation, bed rest and restrictions related to any intellectual work. Gilman herself also underwent this treatment under Mitchell in 1886. For several years, Gilman had suffered from nervous breakdowns and in 1887, she went to Mitchell for treatment, who was then the best known in the country. But he prescribed different therapeutic treatment for men and women for the same condition: neurasthenia, which involved nervous breakdowns which Gilman was also afflicted with. Mitchell’s “rest cure”, however, was in striking contrast to the “West cure” that he had suggested for men – a regimen which included physical exercises, travelling, and male socialization, all for the same symptoms of nervousness, depression, anxiety, and insomnia among others as women underwent.

Also read: Yentl Syndrome: Gender Data Gaps In Medicine & Its Implications For Women’s Health

Gilman’s own experience under the physician is highlighted. She refers to him in her story, saying that he is just like her husband. The narrator is not allowed by him to visit her cousins socially despite her repeated requests. She wishes to write but always has to do it on the sly, clearly having no freedom to follow her mental pursuits. Forbidden from any socialization or intellectual stimulus, she believes that this treatment instead of curing her is exhausting. Under the “rest cure”, the pen, brush and paper were categorized as detrimental to the mental health of patients, and the household was the hospital. There is no evidence of any physical torture upon her but coercive control and psychological torture as she herself describes.

Besides being dismissive of her mental health, John is also patronizing, calling her “little girl” and claiming that since he is the doctor, he knows more about her health. When she asserts that she is not getting any better, he tells her, “She shall be as sick as she pleases”.

For all the infantilization, the protagonist of The Yellow Wall Paper shows acute intelligence and observation. Besides being fully aware of her deteriorating health, she describes the colours and patterns of the wallpaper, its dynamism and how the shades and shapes are ever-changing in conjunction with daylight and nightlight. She draws analogies between the artistic patterns and human figures, fungi, elaborate arabesques, etc. She is well aware of the peculiar damp smell that emanates from the wallpaper which gets worse and all-pervading during the rainy days.

She is incredibly perceptive as the patterns on the yellow wallpaper she observes increasingly seem to form the image of a woman behind bars, perhaps projecting her own condition on the wallpaper. Sometimes it seems to her to be more than one woman. In some spots, the woman in the wallpaper seems to hold the bars with her hands and shake it hard. She even catches her husband and the housekeeper observing the paper and its forms in the way they scrutinize her. Sometimes she glimpses the woman creeping outside the door in the garden. She says that it must be humiliating to have to creep and avoid suspicion even during daylight, perhaps another indication to herself having to write stealthily without her husband noticing. In the end, she manages to free the painted woman by peeling apart much of the wallpaper and its bars. Whether it is an indication of her liberation or the progression of her disease is left to the imagination of the reader. But Gail Marshall, professor of Victorian literature and culture at the University of Reading, says of this, “What we are looking at here is a powerful moment of women coming together to act collectively.”

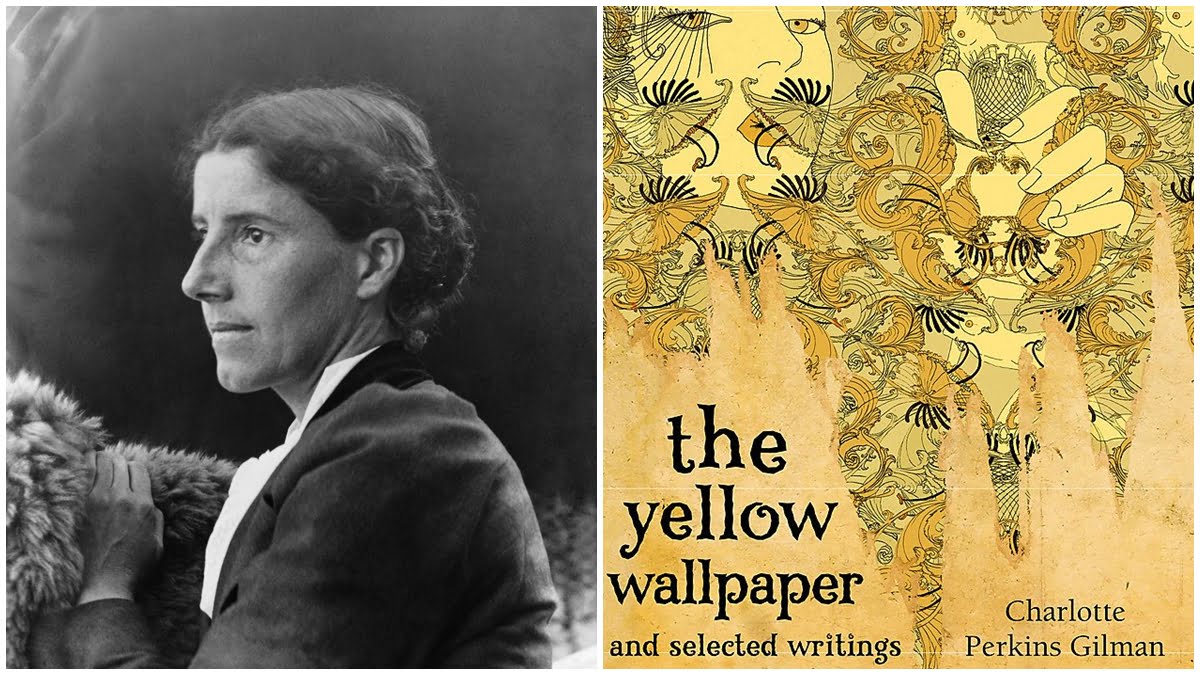

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was an American feminist and writer and one of several women suffragists, writers and scientists of her time who thought that sex and gender issues have been neglected by male scientists and advocated for the reform of women’s state in society. Through “The Yellow Wall Paper” she highlights gender relations and how women’s health was viewed in the 19th century. Yet it should not be relegated to a remote medieval century and instead should be considered as a part of the literature that has and continues to present the gender disparities in medical science.

Also read: Tracking The Painful Credibility Deficit Of Women

John, the physician, diagnoses his wife’s condition as “a slight hysterical tendency”. The story was published in 1899. The 1880s had witnessed the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud attribute hysteria as a mental disorder exclusively to women. In 1895, Studies on Hysteria had been published. Freud is one of the many stalwarts of science, who with their scientific studies and observations marred by prejudice have not only excluded women out of science, but utilized that very field to further the inequalities between men and women. But revisionist studies to medical treatment are important to gain newer insights and rule out old errors arising due to several reasons including culture and social order.

Although initially met with mixed and varying reviews, Gilman’s story, as claimed by the author herself in an article published in 1913, led to Silas Weir Mitchell himself altering his treatment of neurasthenia. The family of another woman, who was also suffering from similar symptoms, allowed her to return to normal activity from confinement which led to her recovery.

When gender stereotypes and prejudices are claimed to be backed by science, they are even harder to challenge and dismantle. Medical practitioners have the power and the privilege to diagnose health conditions, and they are cognizant of this fact. As the narrator is asked by her husband himself, “Can you not trust me as a physician when I tell you so?”

The story sheds light on the cultural and sexist stereotypes that exist in patriarchal societies which aim to confine women to households on the pretext of their health and diseases. The social order contributes greatly to how the health of different sexes and genders are viewed, understood and treated. The differences between the “rest cure” and the “West cure” are indicative of that, and how misdiagnoses and mistreatments of mental health can also be instruments of oppression. When gender stereotypes and prejudices are claimed to be backed by science, they are even harder to challenge and dismantle. Medical practitioners have the power and the privilege to diagnose health conditions, and they are cognizant of this fact. As the narrator is asked by her husband himself, “Can you not trust me as a physician when I tell you so?” But they should also be aware of the responsibilities that come along with it, and the sexism that have historically maligned their field. Until the 1970s, “The Yellow Wall Paper” was categorized in the Gothic horror anthologies, and perhaps rightly so. What is horrific if not the repeated dismissal and even mistreatment of one’s health by medical science and doctors, which can make it much worse, creating terror within the familiar and the familial, as experienced by the narrator? Medical misogyny can not only be detrimental to women’s health but can also be deathly.

Deeplakshmi Saikia is a PhD research scholar of Visual Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She can be found on Instagram and Twitter.