Among many things, Bollywood is famous for its “romantic” (stalker? sexist?) heroes, picture perfect heroines and the sacrificial Maa. But while some of these stereotypical characters always remain a topic of conversation and controversy, what always escapes a candid talk, is the picture of the father: the unshakeable center of power in the household, the disciplinarian, the decision maker.

It is this infallibility of Bollywood fathers that is often portrayed as part of their charm – the “uncompromising” Yashvardhan Raichand of Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham, the disciplinarian Nandkishore Awasthi from Taare Zameen Par and the “izzatdar” Bladev Singh of Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge.

It would be useful to locate the patriarch (the father figure alone in some cases or the parent as a single unit) within the larger history of the rise and making of state to analyse how the father assumes such a position of power in families.

Patriarchy is as old as the idea of the “state”; the centralised political system which governs its residents. Gerda Lerner in her paradigmatic work, The Creation of Patriarchy, has noted the correlation between the rise of the state and the parallel rise of patriarchy. This is an interesting correlation, for it hints at the idea that patriarchy is not just a way of female subjugation but perhaps also a way of disciplining subjects who the state now cannot directly regulate as it expands.

It is not just the range of “punishments” that is horrifying, it is also the extent to which these ideas are deemed normative and culturally acceptable. Perhaps, the parent-child relationship is the only relationship where tyranny is normalised and even deemed acceptable. The nature of control is so absolute, that any dissent leads to one becoming a recalcitrant child at best and an outright disgrace at worst

Joan Scott, a prominent gender historian in her work, Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis, discusses how gender is not merely an expression of identity but also symbolises a relation of power. To this end, Michel Foucault’s work which talks of postmodern ideas of power that are mediated not directly by visible force and coercion but rather through constant surveillance and discipline via an all pervasive web instead of a singular foci of power, helps us understand the need for an all powerful patriarch, for it is through him that the state stabilises its rule.

In this world view then, the home is a domain within state or to put it otherwise, “a state within state”. Thus, parents become symbolic representations of the head of state. It is perhaps for this reason, that parricide is morally more vehemently denounced in stories and myths vis a vis other forms of murder; for anytime the foundations of the home are shook, patriarchy is shaken, the walls of the state are shook too.

Also read: The Parenting Philosophy Of bell hooks: There Is No Love Without Justice

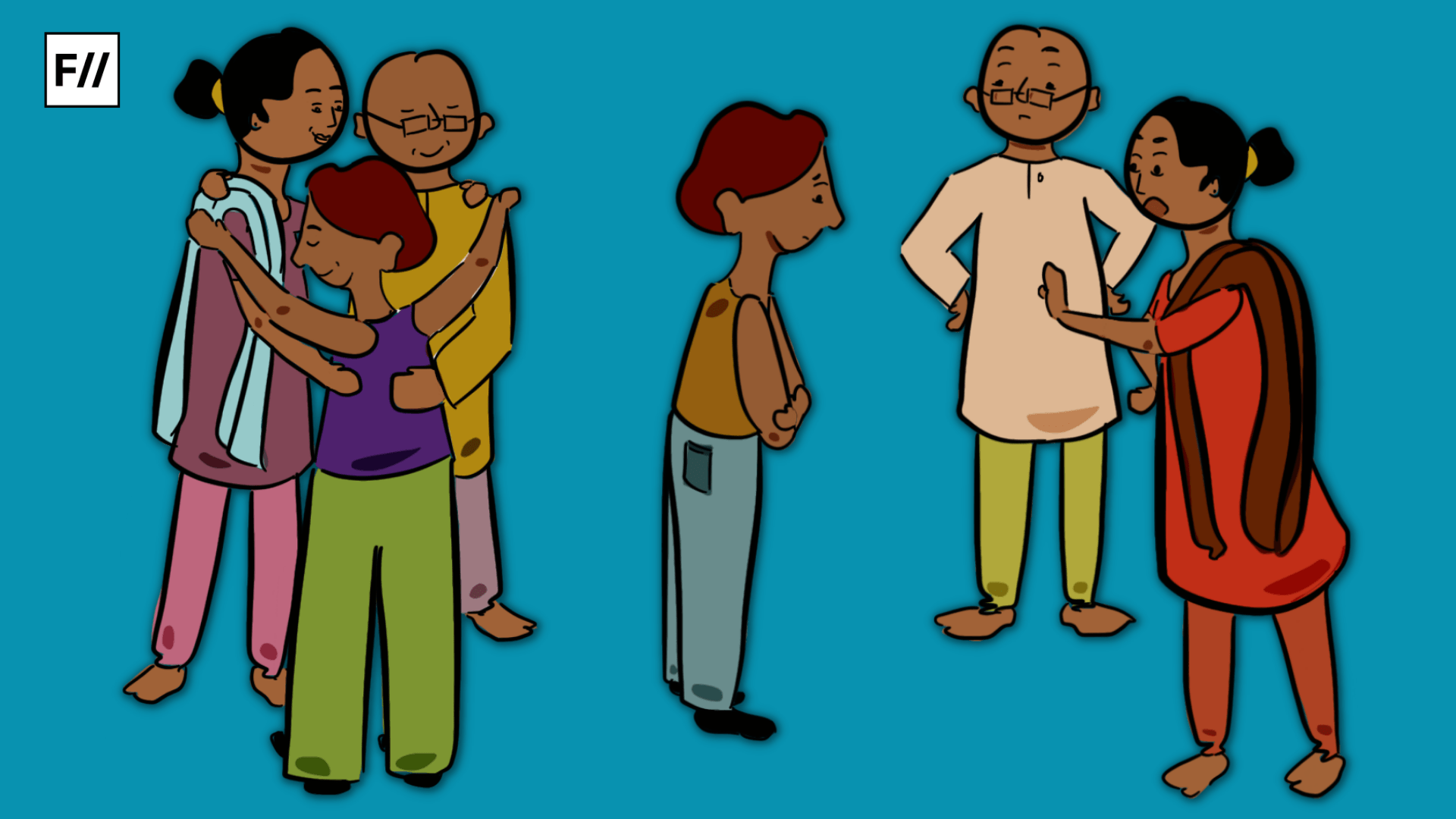

To understand how the home mirrors the state, one only has to see the commonalities between the rulers in their respective domain. Parents (and state) use a combination of “affection” and “punishment” to discipline children(subjects). Just like the state, it is only the parent who can punish (though never punished) and determine offenses.

Not only that, often the “punishment” is coded in a language of love. For instance, Nazir Ahmad, in his book, Bride’s Mirror notes, “Although little children in their folly may not think so, even the pain which comes to you from your father’s or mother’s hands is really conducive to your own advantage.” To our generation, the idiom “tough love” is a parental imperative, maybe rather familiar.

A study published in 2020 by the UNICEF to survey parenting practices and early childhood care has shown that parents depict 30 forms of violence and abuse within a household and that children aged 0 to 6 are the primary targets of the same.

Yasmin Ali Haque, a UNICEF representative in India said, “The various forms of violence against children includes physical violence (burning; pinching; slapping; beating with implements like stick, belts, rods) verbal abuse (blaming; criticizing; shouting; use of foul language); witnessing physical violence (towards one parent; towards siblings; outside the family) and emotional abuse (restricting movement; denying food; discrimination; instilling fear,”. The finding of the report also noted that the pandemic has exaggerated the extent and nature of violence as families struggle to cope with altered social, economic and material realities and children become an easy venting side.

To many of us, the idea of a parent disciplining their child seems “normal”, a rite of passage of one’s childhood. However, it is imperative to get out of the shell into which many of us are conditioned and a more insightful way of understanding this would be to transport the violence of one party and helplessness of the other party, as characteristic of the parent-child relationship to an adult relationship. Perhaps then, the darker undertones of parent-child relationship can come into a sharp focus

It is not just the range of “punishments” that is horrifying, it is also the extent to which these ideas are deemed normative and culturally acceptable. Perhaps, the parent-child relationship is the only relationship where tyranny is normalised and even deemed acceptable. The nature of control is so absolute, that any dissent leads to one becoming a recalcitrant child at best and an outright disgrace at worst.

But if social ostracisation and coercion fail, parents weaponise emotions through appeals, systems of gratitude and instilling feelings of indebtedness.

The advent of digital media has created new forms of “ownership” of children that parents now exercise. This has been compounded during the pandemic where children are physically dislocated from a world outside home and consequently, from support systems rendered via friends and teachers. These children participate in their parents “everyday impromptu” Youtube Shorts, TikTok and Instagram Reels without the ability to consent meaningfully to this participation.

To many of us, the idea of a parent disciplining their child seems “normal”, a rite of passage of one’s childhood. However, it is imperative to get out of the shell into which many of us are conditioned and a more insightful way of understanding this would be to transport the violence of one party and helplessness of the other party, as characteristic of the parent-child relationship to an adult relationship. Perhaps then, the darker undertones of parent-child relationship can come into a sharp focus.

Also read: How Family Vlogging Invisibilizes Children’s Consent

bell hooks observes, “There is nothing that creates more confusion about love in the minds and hearts of children than unkind and/or cruel punishment meted out by the grown-ups they have been taught they should love and respect. Such children learn early on to question the meaning of love, to yearn for love even as they doubt it exists.” Parental violence and abuse then, not only lead to an emotionally convoluted world for children but as research has shown, also to life-long psychological trauma .

Sweet homes and perfect families, marked by “well disciplined children”, are built on blocks of love and abuse. In this race for picture perfect lives, children are always the collateral damage. They are reared in a paradoxical relationship of love and abuse, indebtedness and sacrifice and the results are a lifetime of trauma and fear.

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Harshita is a public policy consultant working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and disability. An alumna of Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, and the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, her work draws on her training in History and Development Studies to unpack gender as a social and structural construct.