The Union Budget for FY 2022-23 Budget Estimates (BE) allocated INR 83,000 crores to the Department of Health and Family Welfare (HFW). But while this remains nearly the same as 2021-22 RE of INR 82,921 crores, it is a 33 percent increase from the pre-pandemic era (2019-20 FY). In line with the technology-enabled development approach, the new budget proposed to set up a National Tele-Mental Health Programme for better access to quality mental healthcare services. Within this, 23 dedicated centres will provide free tele-counselling, under the aegis and direction of the National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro-Sciences (NIMHANS) with technical support provided by IIIT Bengaluru. Moreover, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman emphasised the upcoming development of a digital health ecosystem in the country: “It will consist of digital registries of health providers and health facilities, consent framework and universal access to health facilities.” This announcement got widespread media coverage as mental health’s ‘rare mention’ during the Union Budget speech, indicating its long-deserved mainstream acknowledgement.

In line with the technology-enabled development approach, the new budget proposed to set up a National Tele-Mental Health Programme for better access to quality mental healthcare services. Within this, 23 dedicated centres will provide free tele-counselling, under the aegis and direction of the National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro-Sciences (NIMHANS) with technical support provided by IIIT Bengaluru.

Is the positive feedback premature?

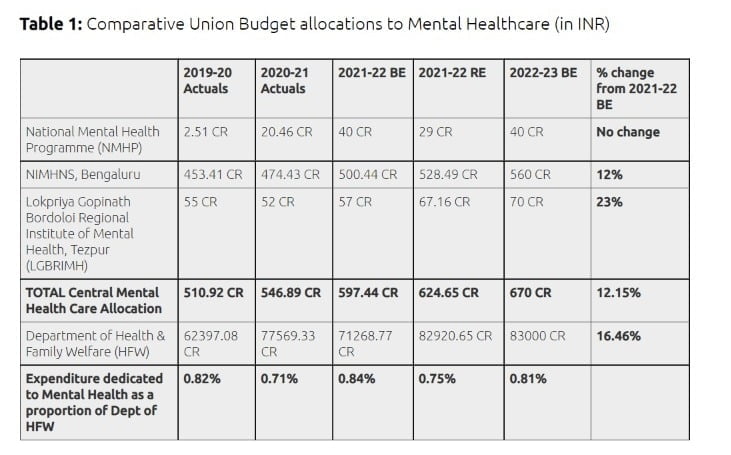

As shown in the table below, compared to the 2021-22 BE, there is a 12.15 percent increase in the Centre’s budget for mental health. Nonetheless, this growth is limited to two centrally-funded institutions while no change has been designated to the nationally-funded National Mental Health Mission other than notable under-utilisation of funds during revisions. At the same time, it is also important to note that less than 1 percent of the total HFW budget has been dedicated to mental health services in the past four FY budgets. Despite increased conversation and the need for such services, the prioritisation of resources remains bleak.

Amongst the 47 government-run mental health institutions in the country, only two out of the three centrally-run mental health institutes have received 94 percent of the total fund allocated to mental-healthcare. The Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, regardless of it being one of the only three centrally-recognised mental health institutions, will receive only a split share of the 1,016.43 crores under the Centre’s establishment expenditure, which is to be distributed amongst 10 or more research and education centres. Of all this, NIMHANS is assigned INR 560 crores, which is also responsible for the proposed Tele-Mental Health Programme. But now, in the absence of any clear mandate, this brings us to question if NIMHANS is solely responsible for funding the entire programme?

Concentrating capacity and resources to merely two institutions prohibits diversity in service offerings while limiting professional services in terms of knowledge-creation and geography. Only researchers and health practitioners subscribing to generously-funded government institutions and private organisations will benefit in the long run as this service will not penetrate to the grassroots as rapidly as we hope. This restricting move renders it an ‘elite’ service accessible to only the few who can afford private mental health practitioners. Moreover, the scheme and its interaction with private players, civil society, and non-governmental organisations remain minimal.

The Mental Healthcare Act 2017 recommends integrating general and mental healthcare services at all primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in all government-run health programmes. This would require extensive training and capacity building. Moreover, the expansion into tele and digital health initiatives needs to happen with equal focus on enhancing gender-equitable internet coverage in the country.

The data monitoring systems of the DHMP and the overall umbrella NMH Programme need to be robust and track gender-age disaggregated data to ensure transparency and logic behind the allocation. Currently, the financing is scattered and insufficient to cope with the mentally unwell population. The Finance Minister’s Budget speech began with high promises of empathy, but sadly words alone can’t help us tackle the complexities of this hidden epidemic. In a country with a 200 million population with some form of neurological or mental disorders, the current management and financing can leave the mental health system overwhelmed and undermined. At the same time, it nudges us to think in the direction of wellness, but does not fully prepare us.

Mental health crises are no longer limited to big towns or small groups. It is no longer a hidden epidemic. It is affecting populations worldwide and calls for targeted investments in human capital. A current policy blindspot, improvement of mental health services—both telehealth-based and otherwise—is a low lying fruit, with a promise of tremendous gains in human well-being across the country.

Studies show one out of three COVID-19 recovered patients will likely have some form of neurological or mental disorder. The stagnancy of the NMHP hurts the national COVID-19 response and the overall preparedness of the health systems to deal with long-term impact of the virus. The systems remain inadequate in dealing with collective trauma and grief and neurological deficits emerging out of Long COVID.

The digitisation in mental healthcare further looks half-baked as no significant provisions have been made to the tele-medicine category since FY 2020-21. The budget allocation only increased due to the massive public need for remote COVID-related services. But the funding does not reflect a long-term promise.

But more importantly, the access and the relief-seeking group was dominated by men, even with teleconsultations. This can be explained by the fact that awareness-raising for such helplines was done predominantly through online media and social platforms when as per NFHS-5, only 33 percent of women in India have ever used the internet compared to 57 percent of men. Further, adult women are 15 percent less likely to own a mobile phone than men. Hence, when the internet coverage lies at only 55 per 100 people, the question arises, what kind of digital access and connection are we rejoicing about?

Historical under-utilisation of funds and widening treatment gap

While the table discussed above covers only direct Union-funded mental health work, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment also dedicates an unclassified amount to neurological wellness by implementing the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2016 Act. It also started the KIRAN Helpline in 2020 to help callers through anxiety, mood disorders, insomnia, depressive symptoms, and more whose running in the future remains to be seen post the announcement of this new tele-mental health programme.

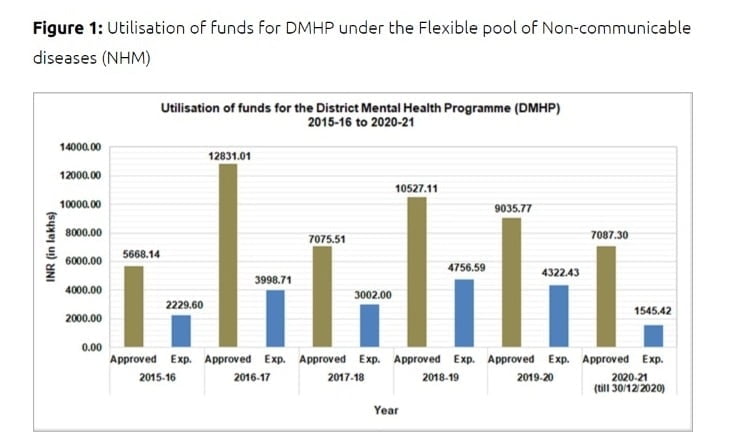

The District Mental Health Programme (DMHP), a component of the NMHP covering 692 districts across states/UTs, is supported by the flexible pool for non-communicable diseases under the NHM. As seen below, under-utilisation of funds is visibly evident, wherein more than 50 percent of funds have remained unused in the past six years. Some independent evaluations of the programme blame the delay in access and unsynchronised integration with other health schemes on the ground as significant deterrents to streamlining service delivery.

Another reason why the DHMP is failing is the mismanagement and lack of awareness on the distribution of funds at Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and Community Heath Centres (CHCs). The referral from a primary to a district centre causes patients to drop out without ever getting a consultation. Additionally, the mental health infrastructure has several gaps and disconnect with the broader healthcare system, which the viral pandemic has exacerbated. Primary physicians aren’t trained to identify mental illnesses and trauma and, therefore, cannot direct patients to places where they can receive adequate care. Emotional first-aid should be mandatory training. The unavailability of trained and motivated staff also worsens this perpetual challenge for the NMHP since its inception in 1982. India has a meagre of 0.75 psychiatrists per 100,000 compared to the desirable three and six in high-income countries per 100,000 population.

A multi-country survey by the World Health Organisation (WHO) found that nearly 76-85 percent of severe cases of mental illness go untreated. The latest Mental Health Survey 2016 conducted by the NIMHNS estimated that only one out of 10 people with mental health disorders receive evidence-based treatments in India. The study further found that for common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders, the treatment gap is as high as 85.2 and 84 percent, respectively. While for severe mental illnesses and suicidal risk, the cracks were still as high as 74 and 80 percent, respectively.

Shift priorities to cover more ground

As per the Economic Survey 2021, India’s health sector expenditure in the FY 2021-22 BE amounted to only 2.1 percent of the GDP. But this increase from the 1.3 percent pre-pandemic, is in line with the goal of 2.5 percent of the GDP envisaged in the National Health Policy 2017. But the progress is not parallel for mental health care in the country. But with the NHMP, the budget needed to diversify its investments to ensure its impact was far-reaching. More researchers and skilled professionals should be engaged in government services to truly make a difference.

The Mental Healthcare Act 2017 recommends integrating general and mental healthcare services at all primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in all government-run health programmes. This would require extensive training and capacity building. Moreover, the expansion into tele and digital health initiatives needs to happen with equal focus on enhancing gender-equitable internet coverage in the country.

The data monitoring systems of the DHMP and the overall umbrella NMH Programme need to be robust and track gender-age disaggregated data to ensure transparency and logic behind the allocation. Currently, the financing is scattered and insufficient to cope with the mentally unwell population. The Finance Minister’s Budget speech began with high promises of empathy, but sadly words alone can’t help us tackle the complexities of this hidden epidemic. In a country with a 200 million population with some form of neurological or mental disorders, the current management and financing can leave the mental health system overwhelmed and undermined. At the same time, it nudges us to think in the direction of wellness, but does not fully prepare us.

Mental health crises are no longer limited to big towns or small groups. It is no longer a hidden epidemic. It is affecting populations worldwide and calls for targeted investments in human capital. A current policy blindspot, improvement of mental health services—both telehealth-based and otherwise—is a low lying fruit, with a promise of tremendous gains in human well-being across the country.

This article has been republished from orfonline.org with permission.