Editorial Note: Being Feminist is a fortnightly column that features personal narratives documenting the emotions, vulnerabilities and innermost contradictions every feminist encounters while trying to push through various degrees of patriarchy in private, professional and public spaces.

Only a mosquito repellent could diffuse my anger at the loss of the siesta on a cold afternoon. Although I knew these creatures feared nothing, I searched the house for repellents. Nothing. “Your Baba (father-in-law) is no more. We don’t need repellents.” I was stunned. Maa (mother-in-law) went on, “He couldn’t tolerate mosquitoes. I would always have extra stock of repellents. Now…“, her voice trailed off.

“Now mosquitoes aren’t biting anymore, are they?“, I snapped, immediately regretting my insensitivity towards a grieving wife. “A woman is nothing without her husband. You won’t understand“, her eyes protested at what she felt was my insolence. I immediately left the room and dashed to the terrace to let the chilled February wind remind me of my resolutions. But the question nudged at me again – Will I ever make sense to her? I was at my in-laws’ place in Coochbehar to attend a family wedding, and to try to solve this puzzle between us.

Tradition is a relay race – the baton must be passed on, tracks shouldn’t change, speed shouldn’t slacken. You lose the race if all the factors aren’t well coordinated. I think she sensed defeat when I confronted her for the first time on the compulsion of wearing sarees, especially inside the house. Why should I feel like living in a guest house and not at home? How could I make a home of this house and a family out of unknown people when I was being forced to do something I wasn’t comfortable in?

The confusion had emerged early on when I married the eldest son of the third generation in this joint family. I had found the subtleties of a joint family bewildering. You have not grown up in a joint family – was sprayed indiscriminately at my dilemma to wipe it off, as if prior experience alone should matter where rationality could be applied. Befuddled, I tried to understand the necessity of a 23 year old to drape a saree every time she was at her in-laws’.

I tried to deal with the ostracising of a woman during her periods; most significantly, I tried to understand what made a woman the woman of a family, and whose example I should follow. With daily soaps as precedence, I tried to act my part. But whenever I stopped to question the ‘norms‘, the word ‘tradition‘ was hurled at me.

However, my reasoning self, growing apathy towards dictates, claustrophobia of sarees as well as frames, pitted against my knowledge of feminism made me uneasy. When I recognised the symptoms of patriarchy loud and clear within this joint family, I prepared to launch myself as the revolutionary who would bring home a new awakening. I knew I had to start with the woman who was zealously leading the march of patriarchy, and bring her face to face with the underlying realities that were escaping her notice. I had to decolonise her mind!

Maa had been working as a science teacher in a school from her twenties. Her belief in proper work-life balance kept her on her toes, while absolving much of her self in the hullabaloo. Living in a long distance marriage, where her husband was, perhaps, more enthusiastic about the family than her, this dedication might have been the only way for her to express herself, all else being invisible.

Powered by the fictitious notion of being the woman who held the family together, she became the revered boro boudi (eldest sister-in-law) whose individual wishes slowly withered away in this gamut of sacrifice and glory. I was uncertain if my petite frame would be able to shoulder such a burden.

Tradition is a relay race – the baton must be passed on, tracks shouldn’t change, speed shouldn’t slacken. You lose the race if all the factors aren’t well coordinated. I think she sensed defeat when I confronted her for the first time on the compulsion of wearing sarees, especially inside the house. Why should I feel like living in a guest house and not at home? How could I make a home of this house and a family out of unknown people when I was being forced to do something I wasn’t comfortable in?

She decided to teach me lessons on tradition; I was a stubborn student. I declared that the tradition which forced daughters-in-law to fit into a frame, to sacrifice their sense of self at the altar of something so flawed, to be oppressive, and, thus in need of change. She must have felt the ground slipping from under her feet when I opposed to do the most natural thing expected of a woman – become someone else after marriage.

Also read: ‘Feminism Is Not A Battle, It Is A Meticulous Surgery’: An Account Of Feminist Vision Through Generations

My aunts-in-law, who were the only daughters-in-law before me in the house had accepted much of the frenzy for the sake of peace within the household. However, they waited for the night time when behind closed doors they could adorn some comfort. I was resolute – no compromise. My mother received the first call- ‘Meye ke bojhan!’ (Help your daughter understand!), and from then on a thousand such calls in the past fourteen years, the last one being six months ago when I said a PhD does not mean I stop studying. My mother told me nothing then, nothing now, but recognised the grounds being prepared for an unresolvable battle.

The last fourteen years have seen us drifting apart because of our differences. While family is everything for her, I consider it only as another essential part of my life. While I cannot exert myself to fulfil expectations, she has done that all her life. While the incantation of “Tumi boro bou” (You are the eldest daughter-in-law) can make me flee the scene, she has borne such responsibilities with credence.

My consistent effort all these years has been to make her realise that women of the house, especially mothers and daughters-in-law are not second class citizens who must wait to scrape the charred bottom off the pot. While I have been told how I failed to be the woman who keeps the family together, I asserted that keeping people together is not a woman’s job alone and that it might not be the ambition of all women.

How can we, then, break this cycle of oppression that has historically subjugated and alienated women? I don’t think I have a clear answer to this. May be it’s a process of trial and error where we must prioritise one thing – never to lose out on compassion. While we rightly aspire to be the protagonist of our life’s narratives, maybe we must realise we cannot live in isolation. We are windows opening outwards to the world. We must build empathetic bridges; we must try to understand other versions of existence, even if we do not subscribe to them.

Some might just want to exist while letting others do so. This relative existence is futile which tends to make women lonelier, I said. Feminist theories spoke louder to me as I saw myself transforming into a warrior with a cause. But while the battle was on, the pandemic happened, we lost Baba (my father-in-law), and the lull was difficult to deal with as I realised we were at the point of no return.

That realisation struck a chord – did it have to happen that way? Was it necessary for me to rethink the ways of resistance since a heteronormative, patriarchal family cannot accommodate resistance easily? Were we actually caught in a one dimensional idea of a family?

I wasn’t ready to accept the platter of indignity, oppression, responsibility and expectations served to me as ‘family’, while she found me misfit, insolent, rude and stubborn. My impatience made me move farther away from any negotiation. Why didn’t it occur to me that family as an institution has always used women as instruments to percolate oppression?

Women have mostly accepted such regimes of power within the private sphere out of the fear of being unaccepted, being left alone. That insecurity has also forced women to partake in the viciousness of power, to mark the deviant, to make the upstart invisible, thereby ensuring their belongingness as ‘good’ women. Nowadays, as I watch my aged mother-in-law, made feeble by her loss of authority and her husband, once again striving to belong to the family from altered vantage points, I ruminate – can we forever belong to anything/anyone that is outside us? She waits for the charity of a visit, or a bowl of pomegranates, while I try to introspect.

I try to understand what being a woman has taught me until now, especially in the last two years. I think I can understand better that life appeals differently to different people, and to take away the cause of living from those who are already made vulnerable by oppressive structures doesn’t seem worth any revolution.

How can we, then, break this cycle of oppression that has historically subjugated and alienated women? I don’t think I have a clear answer to this. May be it’s a process of trial and error where we must prioritise one thing – never to lose out on compassion. While we rightly aspire to be the protagonist of our life’s narratives, maybe we must realise we cannot live in isolation. We are windows opening outwards to the world. We must build empathetic bridges; we must try to understand other versions of existence, even if we do not subscribe to them.

The years of feminist journeys should make us accommodative enough to realise that emancipation is never about absolute triumph; it comes with pain that could help us become self-reflective, emotionally independent, but more kind. I cannot feel triumphant when I see my husband suffer because the two most important women in his life cannot find ways to reconcile their contradictions.

He bears the cudgels of the balancing act while I quit. I have still not been able to bring myself to forgetting everything that I have endured. I recognise this burden must not be mine alone. But I am trying to look for ways to attract more sunshine just as I have found a space of my own amidst my books.

Also read: Choosing To Be A Cycle Breaker: Navigating The Generational Trauma Of Parental Abuse

While being conscious of this privilege, I am trying to understand the need for a relentlessly working towards one’s beliefs without the need to conquer the world, without the need to be the messiah, without constantly blaming women stuck in patriarchal structures themselves.

I am trying to understand the means of navigating pain within myself while working with empathy towards building emotional solidarities and change things. But I know nothing arrives intact; we are all striving towards that something called happiness, and it always comes enwrapped in a little chaos.

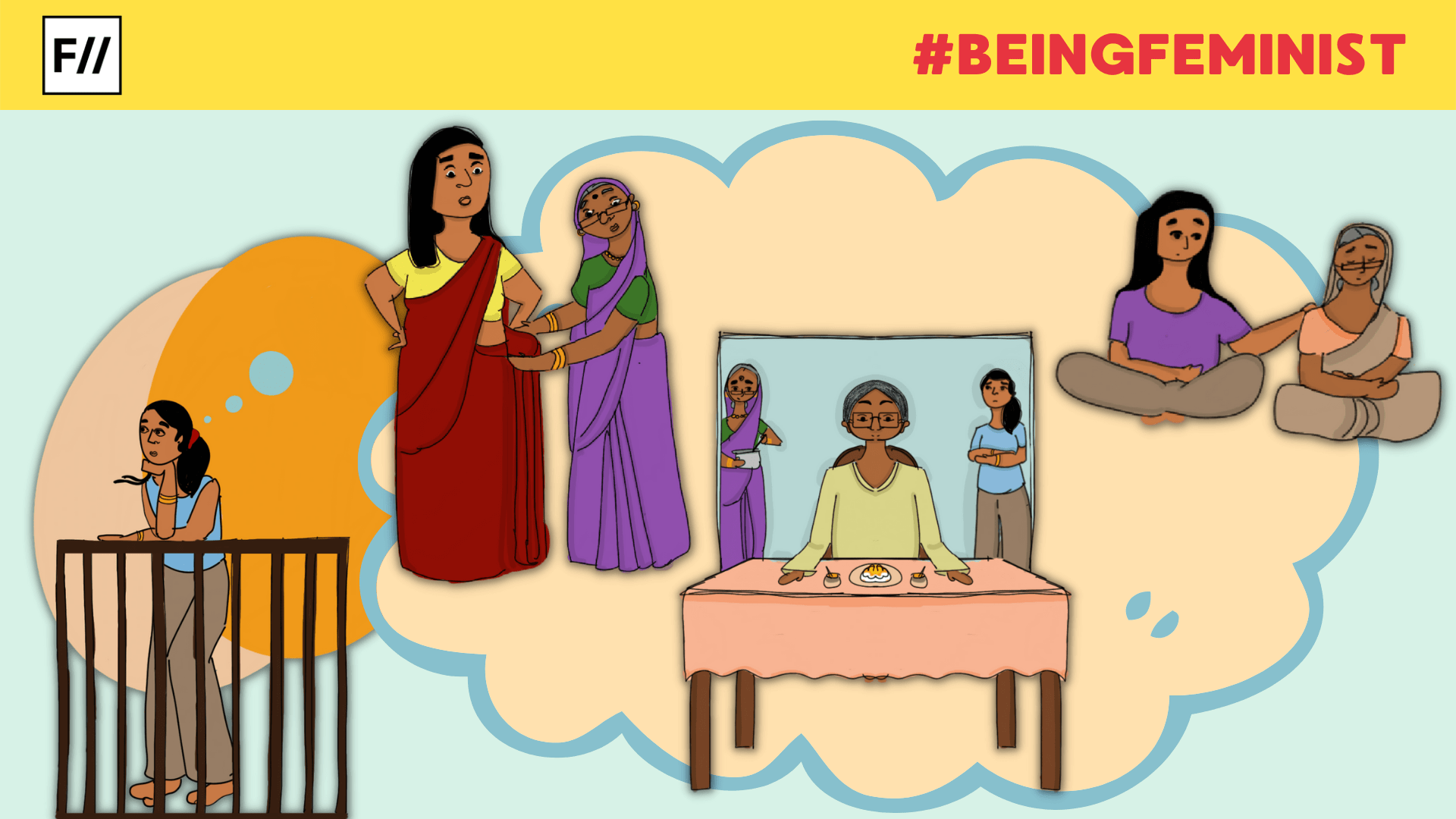

Featured Illustration: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Priyanka Chatterjee is a mother, researcher, and academic. She lives and writes from Siliguri. Her articles have appeared in Feminism in India, LiveWire, Himal Southasian, Sikkim Express, among others. She can be reached at site.surferpc@gmail.com and is on Instagram @priz_chatt