Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak brews a dialogue to which Madhumita Dutta invites us to “listen.” We are solicited, even expected, to listen to these conversations, given how we inhabit varying locations and privileges. The monograph is, then, a welcoming invitation to engage with viewpoints and desires of young women working in urban work sites, women who defy politically correct vocabularies to probe and develop new dialogic possibilities. As they imagine alternate realities and comment on the ones in which they locate themselves, we find ourselves rocketed in fascinating webs of social exchange – to listen.

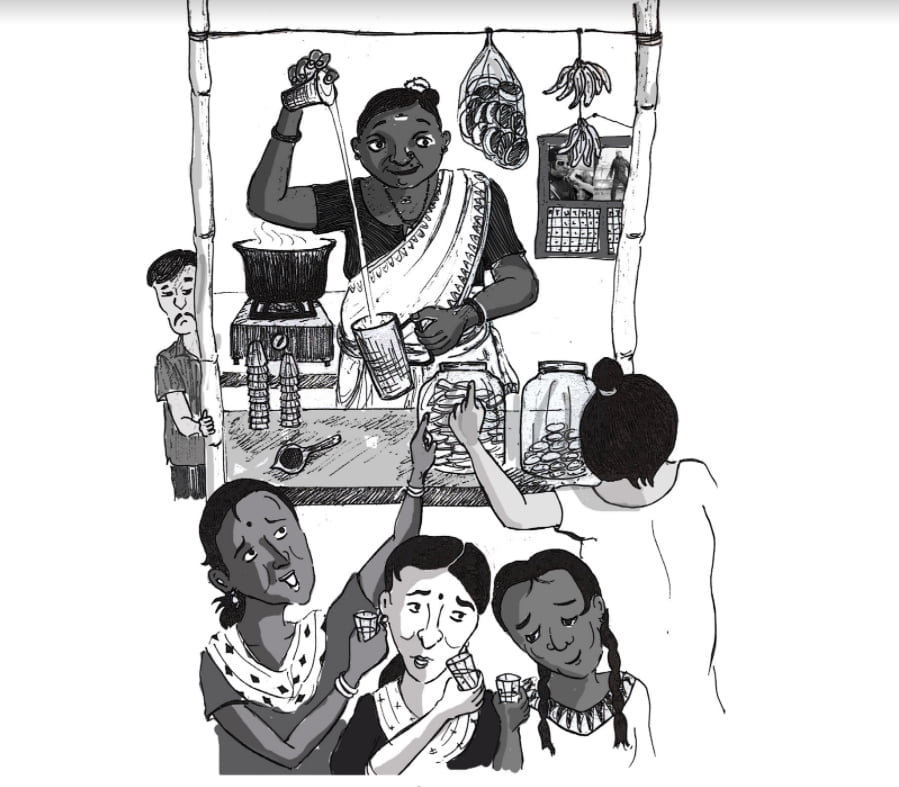

The first conversation begins with a discussion on tea, leading many women to share their hesitation in approaching teashops, which, despite their ubiquity in urban landscapes, continue to be dominated by men. Teashops aren’t simply teashops: they have come to characterise public sites of leisure and recreation. Mobile Girls Koottam highlights how gendered inaccess to public spaces, such as teashops, is maintained by both private concerns of safety and assimilation as well as ever-present socio-familial restrictions.

Also read: Book Review: ‘Beyond #MeToo: Ushering Women’s Era or Just Noise?’ By Tanushree Ghosh

The first conversation in the book begins with a discussion on tea, leading many women to share their hesitation in approaching teashops, which, despite their ubiquity in urban landscapes, continue to be dominated by men. Teashops aren’t simply teashops: they have come to characterise public sites of leisure and recreation. Mobile Girls Koottam highlights how gendered inaccess to public spaces, such as teashops, is maintained by both private concerns of safety and assimilation as well as ever-present socio-familial restrictions.

One impromptu solution proposed in the book by one of the women is the inauguration of a teashop for women. Initial insistence on provision of a teashop that provides exclusive access to women later gets replaced by other ideas of limited or conditional inclusion during the course of their lively conversation. Together, they also reflect on public gaze of onlookers or passerbys and discuss facilities or services that can offer value to the teashop’s customers. A serious commitment to the conception of such a unique space appears to be premised on the underlying hope that its urgency will enable the development of similar teashops. The discussion is inspiring, to say the least!

Their conversations around personal experiences of menstruation are interspersed throughout the book, though there is one section that addresses primarily menstruation. Titled ‘My First Period,’ it features conversations initiated and recorded following a screening of the Tamil documentary Madhavidaai (2012). The documentary film focusses on caste-based practices followed during a woman’s menstruation in some districts in Tamil Nadu. Contrary to myths of contamination upon which many traditions are predicated, it shows that menstrual blood is, in fact, used to make medicines. Accordingly, menstrual blood is “nutritious,” not “waste blood.”

Their discussion makes it evident that their first encounters with menstruation bear many commonalities. For instance, several women disclose that they had to wait for the arrival of their maternal uncle’s wife when they got their period for the first time. Many social taboos to which they are expected to conform are indeed similar, though the precise implementation of the practice may vary from one family to another. The women also imagine social implications if men underwent menstruation like women did, and exchange experiences of menstruation in the workplace.

Another important subject that props up is the social demand to conceal the occurrence and products of menstruation: construction of thatched roofs to camouflage the ‘polluted’ menstruating girl and sale of sanitary pads in opaque plastic bags are common mechanisms of enforcing disguise. Interestingly, such acts contradict extant ‘coming of age’ ceremonies, practiced across several regions, to celebrate menstruation, though most celebrations rather problematically commemorate the onset of a girl’s biological destiny – that is, procreation.

Kalpana, who is not present in the first five episodes of Mobile Girls, joins Sam, the author’s field interpreter, to share her views. She emphasises the significance of resilience and a self-sustaining drive to challenge systems of control, elucidates the impact of increasing urbanisation on gender norms, and critiques the widespread perception of sex as a ‘private’ part of our lives. In responding to Sam’s question concerning accessible sites where women can loiter, Kalpana shares that women who work as wage labourers in the village are “joyous,” adding that “whether they work as construction workers or as sand miners,” they remain joyous, “so much so that they forget how they struggle at work or at home.” Kalpana’s compelling views and personal experiences cast working women outside the stereotype of arduous and oppressed workers, not because such an alternate insight is required, but rather because it reflects a sincere actuality that we deliberately choose to overlook.

The dominant subjects in the remaining discussions include work and romance. Many understand the enormity of housework and consider it additional work. Some are willing to leave factory work to commit to their family after marriage while some are determined to continue professional work after marriage. With regards to factory work, the women seem conflicted as they attempt to determine the difficulty of and challenges involved across departments: there are disagreements on the amount and nature of work across, for instance, ATO and materials departments. They detail management tactics to influence competition and increase output, express their anger at potential layoffs, and survey alternate employment options should the factory close, given the lack of transferrable skills in the options that they have.

Their dialogue on kissing in public opens a conversation on sexual harassment, leading to a discussion on the specifics of a class on sexual harassment in the workplace. They exchange their views on live-in relationships, romance, and marriage. Reflecting on their own experiences, they uncover their strategies of concealing their relationships in their families and discuss the realities of inter-caste romance.

Mobile Girls Koottam is a necessary addition to both academic and public scholarship. It casts individuals who lie at precarious intersections of different identities outside the binaries and stereotypes set for them by mainstream media. Some of the statements made by the women may appear ‘problematic’ to the contemporary cancel culture, which is, I believe, precisely what the book aims to resist and challenge. A dialogue, Mobile Girls Koottam suggests, cannot be initiated unless listening is critically used as a practice to be empathetic to different experiences and life-worlds.

Also read: Book Review: Loki Takes Guard By Menaka Raman

Published by Zubaan, Mobile Girls Koottam is what responsible ethnographic work by a brilliant academic looks like. It invites you to listen to animated conversations recorded in Muthu’s room. As Dutta writes, make yourselves a cup of tea and embrace the free-flowing conversations into which the book heralds you.

Inspired by Richa Nagar, Dutta orients her research process in a conversation and invites her readers to listen. In reflecting upon one of the discussions on the workplace involving one of the working women’s complaint to the HR about two lovers, she admits to her failure in listening and consequently obliterating the women’s everyday encounters with caste and gender relations. Acknowledgements of such lapses in private acts of listening probe reflections on methodology and its limits.

Published by Zubaan, one of the most prominent and incredible publishers, Mobile Girls Koottam is what responsible ethnographic work by a brilliant academic looks like. It invites you to listen to animated conversations recorded in Muthu’s room. As Dutta writes, make yourselves a cup of tea and embrace the free-flowing conversations into which the book heralds you.

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a researcher and a writer. Her work lies in the intersection of feminist theory, postcolonial studies, and popular culture.