Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for March, 2022 is Women’s History Month. We invite submissions on the contributions of women, the trajectory of the feminist movement and the need to look at history with a gender lens, throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

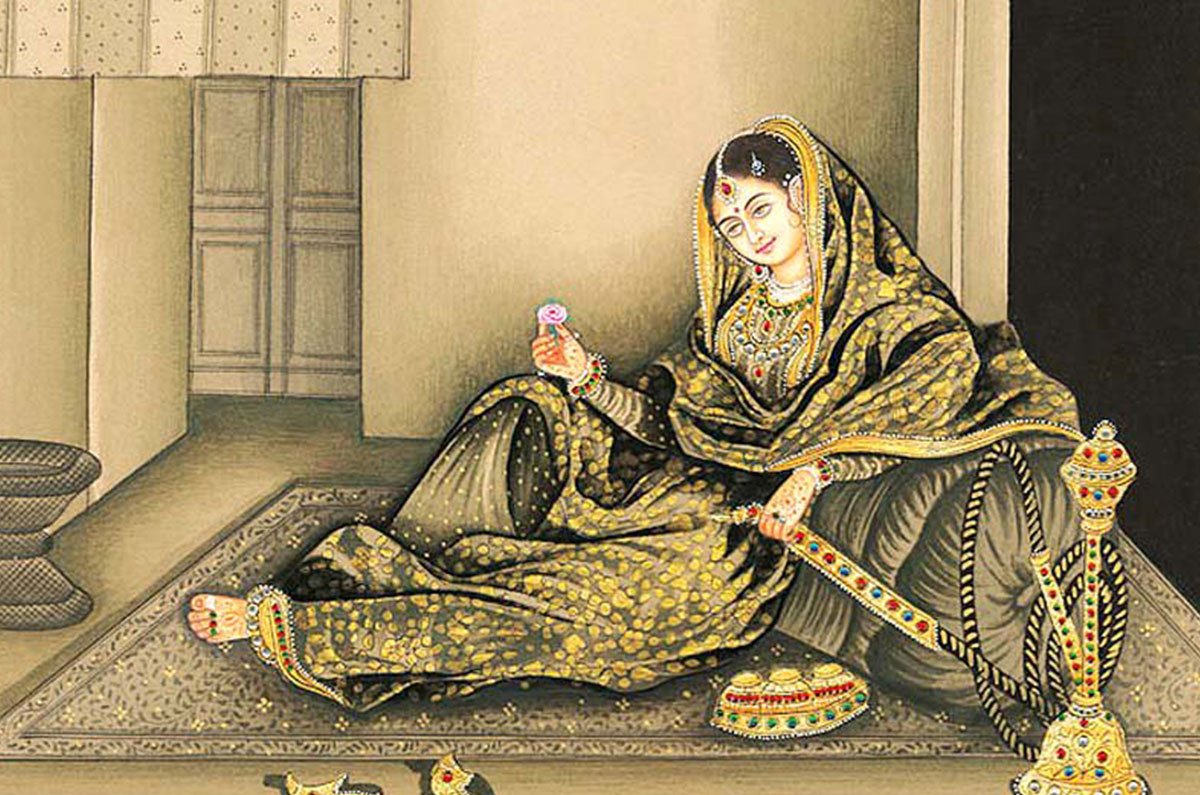

In the early nineteenth century, Lucknow was the undisputed cultural centre of the Urdu-speaking world, famous for its ‘sweet’ language, poetry, dance, and music. An integral part of this culture was Tawaifbaazi, the courtesan culture. But who were the courtesans?

While our history books record the decline of Avadh kingdom following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the stories of the courtesans, who occupied a significant cultural space, has been pushed into the corners. Umrao Jan Ada, an Urdu novel by Mirza Hadi Ruswa, seeks to uncover the narrative our historians have conveniently omitted.

It tells the story of a Lucknawi courtesan, Umrao, an enigmatic woman, whose existence and poetic gifts remain a mystery to this date. The novel falls vaguely under the genre of social realism, woven tightly with the intricacies of culture and tradition. Umrao is a dominant class woman who was abducted from the comfort of her home and sold to Khanum Jan’s establishment.

The novel closely follows Umrao’s life from that point and how its highs and lows flow parallel to those of the courtesan culture and the city of Lucknow.

Prior to the mutiny of 1857, Lucknow was buzzing with the cultural tradition of nazakat (delicacy), nafasat (decency), and sharafat (nobility), all of which are portrayed by Ruswa to be linked with the courtesan culture. These establishments or Kothas, were culturally significant as they were sources of cultural refinement.

The courtesans were not like common sex workers. They were trained and skilled in the arts of poetry, singing, and dancing. Khanum Jan was herself well-versed in these arts and was a powerful woman who ensured her ‘girls’ were given proper education and were fluent in Persian, Urdu, and Arabic.

As Umrao herself says, “The ties of blood are strong but why would any respectable person want to meet me?”, the social structure was made very precise and sex workers had no place in the household domain. When Umrao pleads with her brother in Faizabad to see her mother one last time, he replies, “Get that idea out of your head, you’ve spread enough scandal already”, implying that there is no way a sex worker like her could remain associated with a respectable household

The introductory chapter, Mushaira (poetic-gathering) is an accurate representation of the Nawabi culture in the 19th century Lucknow. Umrao’s delicate way of narrating her story, her ability to recite impromptu ghazals, her diction, are all clear evidence not only of her skills but the etiquette training that the courtesans received.

There existed a certain hierarchy among the courtesans. The thakahis were sex workers who lived in the Bazaar and attended to the common citizens. The khangis secretly took to sex work for financial reasons, but took purdah. Then, there were the tawaifs who were reserved for the aristocratic class and hence, enjoyed royal patronage and favours.

They were respected and were offered jewels and vast sums of money for their performances. They were revered because they were a part of an institution that held a high place in the culture of the city. Ruswa expresses all of this in Umrao Jan Ada by embedding the text with cultural ethos.

Also read: How ‘The Last Courtesan Of Bombay’ Destigmatises Tawaifs And Mujras

Through the characters of Khanum Jan and Bismillah, Ruswa points to the economic power and status that the courtesans luxuriated in. However, after the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the cultural capital of Lucknow underwent drastic changes. There was a substantial shift in the status and representation of women as well as the terminology used to refer to them.

The colonial regime sought out to ‘fix’ the decadent lifestyle of the Nawabs and to imbibe Victorian values into their culture. The courtesans lost their patronage in consequence of the fall of Avadh and were reduced to the status of mere ‘prostitutes‘. Sex work was, in the post mutiny period, seen as the embodiment of allurement and a threat to akhlaq (moral code).

The Indian Mutiny of 1857 resulted in the fall of Avadh and the sharp decline of the Nawabi culture, but perhaps a tale that often goes unnoticed in history is that of the courtesans. Courtesans were once the preservers of a rich culture, were dismissed to be a beleaguered community. At the end of the novel, we see Umrao, like hundreds of other courtesans, with faded glamour as she lives at the margins of the society

The distance between woman as a wife and woman as a sex worker was made overtly clear. Respected women were to be self-disciplined and were to stay inside their households. Sex workers (fallen women) were considered to be women of the streets and were condemned as social evils. No intermingling between the two kinds of women was to be tolerated.

Sex workers were banished from civil society. Respectable women were placed within the private sphere, and therefore the bazaari women, who remained in the public sphere, were pushed to the margins. Both the respectable women and the fallen women were to inhabit their own spheres, the private sphere and the public, respectively.

As Umrao herself says, “The ties of blood are strong but why would any respectable person want to meet me?”, the social structure was made very precise and sex workers had no place in the household domain. When Umrao pleads with her brother in Faizabad to see her mother one last time, he replies, “Get that idea out of your head, you’ve spread enough scandal already”, implying that there is no way a sex worker like her could remain associated with a respectable household.

The courtesans were, hence, pulled away from their huge mansions, and were pushed to the ghettos of the city. They were taxed for their income and subjected to bodily inspections. These women were considered to be merely a source of entertainment for the soldiers. And in order to prevent the soldiers from getting venereal diseases, the sex workers who contracted any diseases were sent to lock hospitals.

The Indian Mutiny of 1857 resulted in the fall of Avadh and the sharp decline of the Nawabi culture, but perhaps a tale that often goes unnoticed in history is that of the courtesans. Courtesans were once the preservers of a rich culture, were dismissed to be a beleaguered community. At the end of the novel, we see Umrao, like hundreds of other courtesans, with faded glamour as she lives at the margins of the society.

References:

- WAHEED, SARAH. “Women of Ill Repute: Ethics and Urdu Literature in Colonial India.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 48, no. 4, Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 986–1023

- Anantharam, A. (2012). A change in aesthetics and the aesthetics of change: A comparative study of premchand’s bazaar-e husn and sevasadan. South Asian Review, 33(2), 177–202

Featured Image: Beyond Pink World

About the author(s)

Apoorva is currently pursuing her Master’s in English from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. When she’s not re-reading the letters by Virginia Woolf, she likes to try her hand at scribbling poetry. Her areas of interest revolve around Feminist Theory and Absurdist Fiction. She can be found brewing tea at midnight, complaining about our Sisyphean existence

The date mentioned in the above para about Indian Mutiny is wrong.