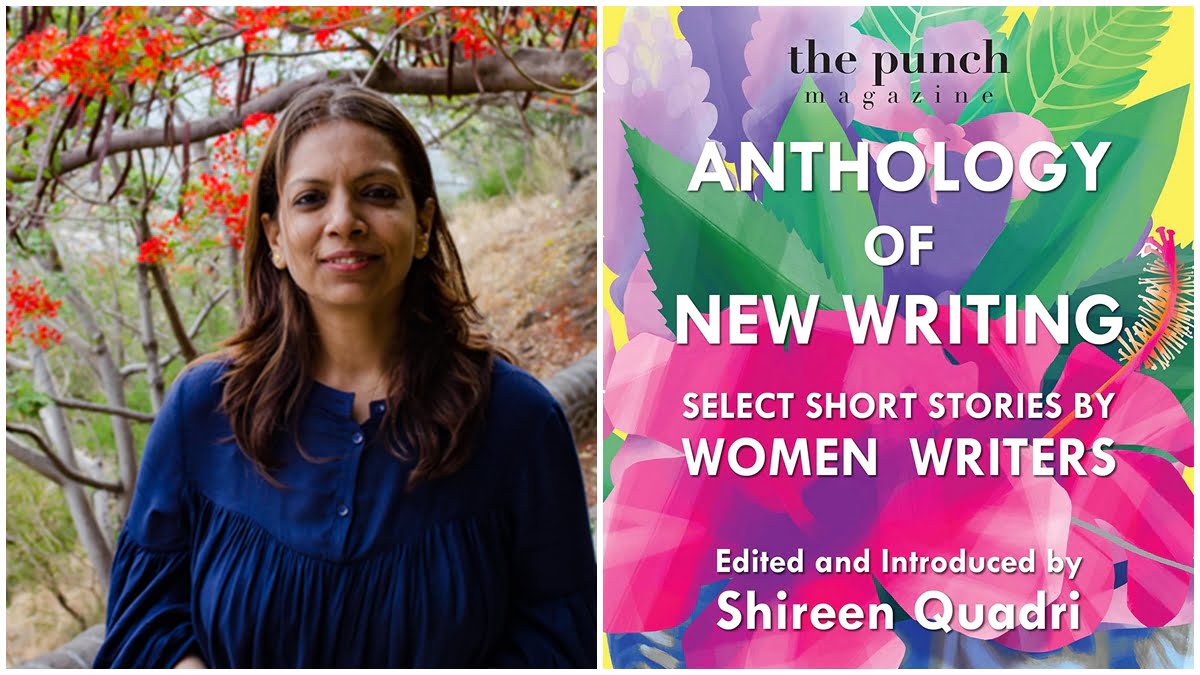

I am biased towards the short story format. It is a format that I love reading and also feel comfortable writing. Some of the most moving stories I have read are short stories, and to me they are nothing short of magical- transporting the reader in a matter of a few hundred or thousand words. As an aspiring writer, I also find it a difficult medium to write in for the same reason: the economy of words. I remember a phase last year, where I read only collections of short stories by authors of different nationalities: Perumal Murugan, Chekhov, Manto, Chughtai, Gulzar, Faulkner, Whitman. There were however, only very few or sometimes no female writers in these short story collections. So, whenever I came across a story by Ambai, Selma Lagerlof, E Pauline Johnson, or Eudora Welty, I treasured them deeply. The Punch Magazine’s Anthology of New Women’s Writing ensures that diverse voices of women are heard and documented.

I read the Anthology Of New Writing twice over before writing this review, to be able to condense its themes, but the diverse stories of the book shatter the homogenisation of the ‘woman experience’ as they are both different in tone and subjects. At its core, like any other piece of art, the book is a commentary on the human condition and connections, particularly situated in our present politics and sociocultural reality. I could even see some of the stories vividly play out in front of my eyes like short films, waiting to be directed.

I read the Anthology Of New Writing twice over before writing this review, to be able to condense its themes, but the diverse stories of the book shatter the homogenisation of the ‘woman experience’ as they are both different in tone and subjects. At its core, like any other piece of art, the book is a commentary on the human condition and connections, particularly situated in our present politics and sociocultural reality. I could even see some of the stories vividly play out in front of my eyes like short films, waiting to be directed.

The first story, Static A.D., is an eerie reminder of life during a pandemic. What is startling is that the stories were called for and finalised in 2019, in our mask-free past. Written in the ‘stream of consciousness’ style, it discusses the multitude of identities and ‘selves’ we inhabit and project. The writing — tired, melancholic, and contemplative, reflects the fatigue and burnout that characterise an entire pandemic generation.

Food, which has become another contentious subject for fiery political debates, is considered a metaphor for community (or the lack of it), to preserve one’s cultural identity in Olya’s Kitchen. Food is at the crossroads of traditionalism and modernity in the story: the conflict between Olga’s traditional Russian delicacies and its trendy, store-bought alternatives. It also describes the unifying blanket of comfort that grandparents represent that is often invisibilised in families. It reminded me of the times I would peek over my grandmother’s shoulder while she would deftly prepare sambar to go with the dosas that were cooking on the other burner. I was also reminded of the comforting movie, Julie and Julia.

A visit to the Dharavi slum was a staple in the Mumbai Darshan trip that was offered to us at school. I don’t know if the people living there enjoy the invasion, perhaps not, who would? Honour, a story about a washerwoman trains its lens on the othering and often superficial gaze that follows slum dwellers. The protagonist, a slum dweller, embodies her fear of ‘being watched’, the collective fear of women in public places. The protagonist must also live with the ghosts of childhood trauma and the pain of living as herself.

Several stories poignantly touch upon the ramifications of the insurgency in Kashmir and the long-term trauma due to the resulting displacement and hostility. As I write this, it is almost as if the story Crossing is playing out in real time in Ukraine. The story centers on the refugee exodus and refers to the refugees as ‘parcels’, only a statistic printed in the obscure corner of a newspaper. The Vacation, details the anxieties of a woman who was uprooted, as her mind unstably flits between the unprocessed grief of her past that spills into her present. Similarly, Kashmir Valley’s Soofiya Bano paints a melancholic image of a mother’s painful wait for her son, who is only united with her in the direst circumstances. A movie theatre, the main location for The Closed Cinema, is ironically named Firdaus, or paradise, which eventually falls in the violence. The experience of art is first martyred during political turmoil.

Also read: Book Review: Time And Race in Octavia Butler’s ‘Kindred’

Love is a predominant emotion in some of the stories. Pandemonium resembles the Tamil pulp-fiction serialised stories that keep my grandmother’s eyes peeled. It could perhaps even be an incident from my mother’s time in college, complete with the flared bell-bottoms swaying to the music of The Beatles. Sunday, Bloody Sunday delves into the complexities of an inter-faith relationship in a seemingly ‘modern’ Hindu family, a reminder that not all love stories are allowed to unfold. In a similar vein, Artichoke, which pivots on a fading relationship, also comments on the paradox of Rome — the cynosure of art and culture, yet whimsical at the same time.

Marietta’s Song, perhaps set in a care facility, is light and lyrical, in sync with its magically real climax. Terms and Conditions feels like reading ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ as an adult — too magical to be real, but nevertheless gooey and reassuring. It thrums with the anticipation and excitement of childhood, transporting me back to my own.

Although, the Anthology Of New Writing is an overall immersive and meditative experience, it suffers from the curse that most anthologies do- the lack of ability to sustain the interest of the reader, since all the stories do not have a uniform impact.

Although, the Anthology Of New Writing is an overall immersive and meditative experience, it suffers from the curse that most anthologies do- the lack of ability to sustain the interest of the reader, since all the stories do not have a uniform impact. I was deeply moved by several stories, but couldn’t even gather my thoughts after reading them. Some were entirely cathartic and I purged all my excess emotion. Some others were purely nostalgic and pleasurable. It, however, collates literary voices I had never heard before and now cannot seem to get enough of. It also changed me as a writer because it expanded my understanding of what literature can be and how it can affect a reader. I will look forward to more editions of this anthology, perhaps more ‘deviant’ voices and lived experiences. The Punch Magazine Anthology Of New Writing is definitely a force to be reckoned with.

About the author(s)

Abhinaya Sridhar is an undergraduate student of English literature. She enjoys documenting her personal experiences and opinions and occasionally indulges in writing fiction. She is a creature of habit and can be found listening to the same classical songs on loop or cooking up a storm in the kitchen. She can be found on Instagram