Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration with Uber India and is based on our interactions with Simran Oberoi, an Uber user.

Simran Oberoi, a working professional based in Bangalore and a mother of two, says that Uber Autos have been a game-changer in her everyday life. She recollects the time when she was 7 months pregnant and had to walk a kilometre from where she lives, just to book an auto to work regularly.

“Even if I was extremely motivated, I had to think several times before I could step out of the house in that condition. Having an app readily available made my experience going to work or even simply stepping out of my home significantly convenient,” she remarks.

Renowned transportation service provider Uber has unveiled its latest campaign Bas Socho aur #chalpado. The campaign includes four short films, each of which highlights the services provided by the brand’s two and three-wheeler travel options. These videos are inspired by the true stories of resilient Indians who have an unbreakable spirit when it comes to conquering obstacles. According to Ameya Velankar, Head of Marketing, Uber India and South Asia, the campaign analysis led to the idea of showcasing real-life tales of individuals who have overcome adversities through perseverance.

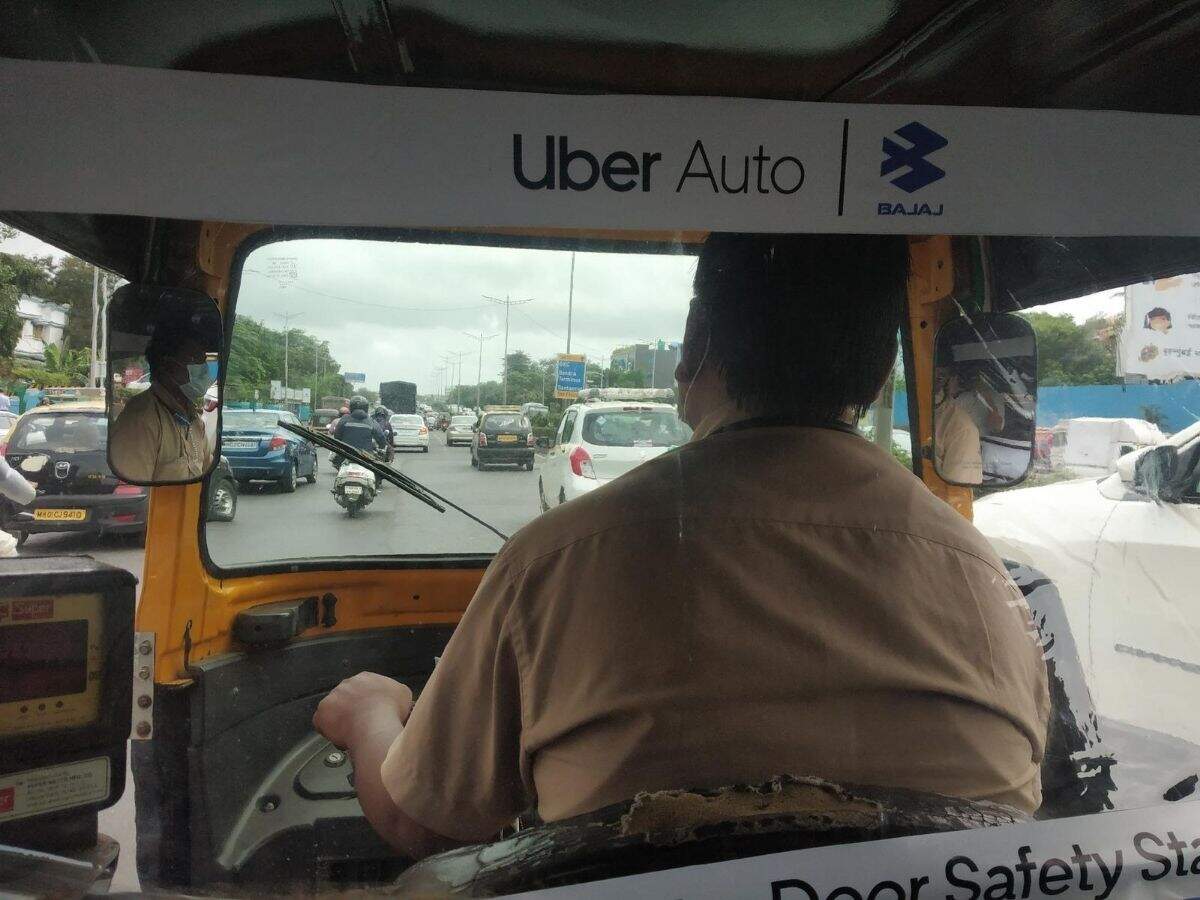

Uber’s initiative illuminates and celebrates the real-life narratives of people like Simran Oberoi, who have overcome insurmountable odds in their lives with their strength and will. The advertorial video “Mom At Work”, which is based on Oberoi herself, gives us a glimpse into the life of a working mother who takes a ride to work on a rainy morning with her infant.

Managing a career while being a mother of two children is no walk in the park, as is evident from Oberoi’s experience. Applications like Uber have made mobility significantly more accessible to women, having a direct impact on their potential to carve a successful career while navigating motherhood. “I personally feel safer in Uber autos than in any cab. Autos are not as restrictive in terms of visibility. There is more comfort present since you can see others and others can see you,” Simran Oberoi says.

One cannot ignore the significant impact transport has on accessibility to education, welfare, and work. Infrastructural development in an urban context has become an essential prerequisite for ensuring sustainability and inclusiveness in the economic progress of developing countries.

Implementing an infrastructure in cities without keeping gender in perspective can lead to the socio-economic isolation of countless people, especially women and people from marginalised identities. As the availability of safe transportation is non-negotiable, it is imperative to research urban mobility from a gendered viewpoint. Men and women have distinct characteristics, choices, as well as concerns regarding mobility and this knowledge must be incorporated into the construction of transportation infrastructure and discourses to promote equal possibilities for participation of women in political and socio-economic spheres of life.

Simran Oberoi says that she has fed her children in a myriad of public places, and it is not always easy or comfortable. However, her experience with these autos has been convenient and safe. Speaking of privacy and comfort while breastfeeding, she observes that since the spread of COVID-19 began, autos began to have a sort of plastic film or PVC partition between the driver’s seat and the passenger’s seat. “I have felt more comfortable with that partition, and maybe that could continue. Besides being an effective preventative measure against the risk of COVID-19 infection, I believe it has made a difference psychologically, not only for breastfeeding mothers but women in general. It has provided some degree of privacy,” she adds

Besides preventing them from participating equally in social, political, and economic enterprises, limitations in women’s mobility also restrict their agency in making their own choices, thereby affecting their overall quality of life. Mobility and labour are inextricably intertwined. Inadequate access to mobility and lack of safety during a commute are seen as the most significant barriers to women’s workforce participation in developing nations, significantly lowering their likelihood of involvement by 16.5 per cent, as per the International Labour Organisation’s World Employment Social Outlook—Trends for Women report, 2017. Enhancing women’s mobility is a critical strategy to promote their labour-force participation.

According to an informal economy monitoring survey, women in urban areas are more likely to reject higher-paying jobs that are far away from their homes in favour of lower-paying, local opportunities, primarily because urban transportation does not cater to their needs of accessibility, security, convenience, and privacy.

Simran Oberoi says that commute was an enormous issue for her and that she would perhaps have not been able to rejoin work without hesitation after childbirth if not for the convenience and accessibility that having Uber autos provided. “Children are usually impatient. Walking for a kilometre with my four-year-old son while I was heavily pregnant, and then waiting for an auto was no easy feat,” she recalls. She considers the initiative of Uber autos a significant one because she no longer needs to wait for several drivers to reject her request for a ride or haggle over the price. It has reduced her stress about commuting from one point to another substantially.

Also read: The Ever-Curious Elbows Of Indian Men In Public Transportation

Women, especially breastfeeding mothers, find it extremely difficult to feed their children on public transport. Women often also rightly express grave anxiety about their safety because of restricted access to urban transportation. According to the Asia Foundation’s Women and Mobility study, 50 per cent of sexual harassment incidents against women in urban areas occurred when using public transportation and 16 per cent while having to wait for public transportation. This alarming figure demonstrates the critical need for increased attention to women’s safety in public transit and infrastructure.

However, an effort like the one outlined above offers women greater mobility and extends women’s economic and social opportunities. While finding a safe ride to work on a rainy day is not the only challenge that a working mother may have to face, it is unquestionably an important issue that needs to be addressed

Simran Oberoi says that she has fed her children in a myriad of public places, and it is not always easy or comfortable. However, her experience with these autos has been convenient and safe. Speaking of privacy and comfort while breastfeeding, she observes that since the spread of COVID-19 began, autos began to have a sort of plastic film or PVC partition between the driver’s seat and the passenger’s seat. “I have felt more comfortable with that partition, and maybe that could continue. Besides being an effective preventative measure against the risk of COVID-19 infection, I believe it has made a difference psychologically, not only for breastfeeding mothers but women in general. It has provided some degree of privacy,” she adds.

On being asked about her opinions on what could be done to make women’s mobility a safer and more seamless experience, she says that perhaps “employing more women as drivers could be something that would not only make women’s experience even better but also increase women’s participation in the workforce“.

Aside from the fact that she can track her trip while also being able to obtain and share the credentials of the concerned driver, she appreciates the fact that her children enjoy the process of booking Uber autos through the app as well.

Women in patriarchal cultures are often expected to do it all, from maintaining a profession to negotiating gender roles and parenthood. While women have consistently demonstrated that they are capable of accomplishing everything, we must examine the weight of responsibilities that most women have to bear.

However, an effort like the one outlined above offers women greater mobility and extends women’s economic and social opportunities. While finding a safe ride to work on a rainy day is not the only challenge that a working mother may have to face, it is unquestionably an important issue that needs to be addressed.

Numerous other concerns must be acknowledged and dealt with on a social, cultural, and political level systemically, and one mobility service provider alone cannot resolve everything at once. Yet, the endeavour itself is indeed worthwhile.

Also read: Problems Faced By Working Women: Restriction On Mobility, Discrimination And Household Violence

Featured Image: Uber

About the author(s)

Poulomi is a Master's scholar from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, who loves to scribble poetry and write essays just when she can't seem to hold it all in. Her research interests include feminist studies, postcolonial theory, trauma and disability studies. She is very eager to read anything she can get her hands on, when she is not obsessing over spicy food or sleeping