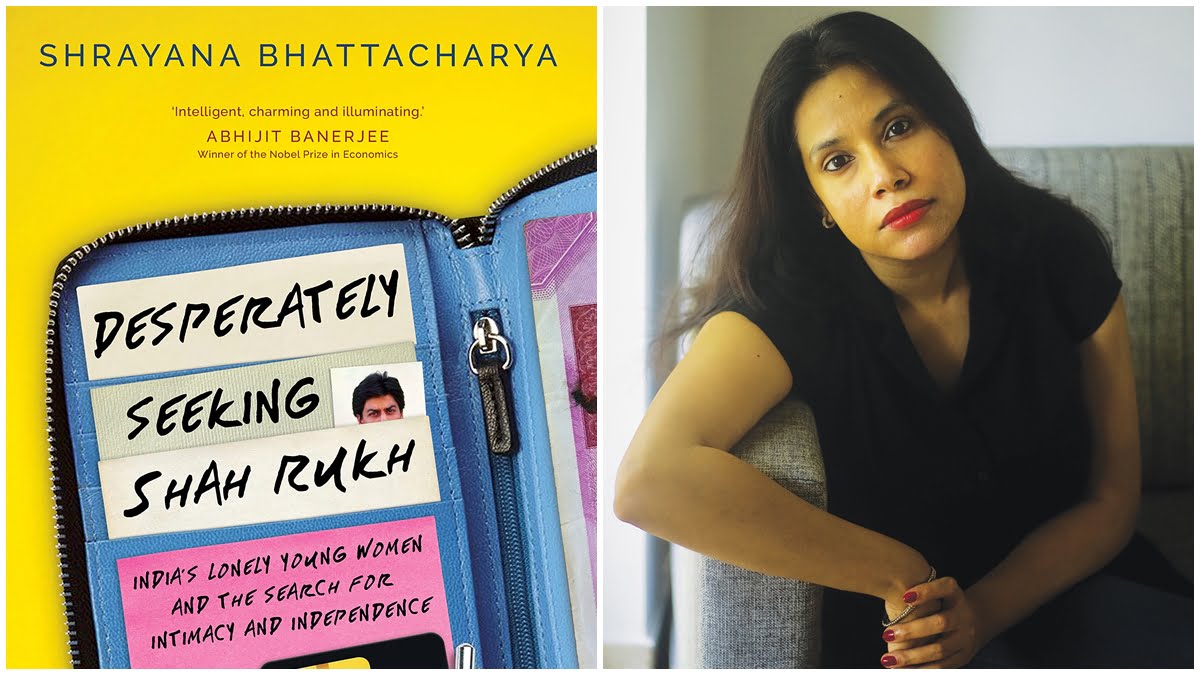

Shrayana Bhattacharya is an economist, author, researcher and an ardent Shah Rukh Khan fan. Her book ‘Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh’ (by HarperCollins Publishers) is currently one of the top 10 non-fiction reads in India. The book, in Shrayana’s own words, is about women and Shah Rukh is but a “research tool”. The book explores the lives, works, economic, social, political and the personal standings and struggles of diverse groups of women divided by class and caste identities but brought together in their love and search for Shah Rukh. It is an attempt to take account of a struggle for freedom as well as a search for the intimacy of Indian women, that Shrayana documented over 15 years.

Shrayana Bhattacharya is trained in development economics at Delhi University and Harvard Kennedy School. Since 2014, in her role as an economist at the World Bank, she has focused on issues related to social policy and jobs. Prior to this, she worked on research projects with the Centre for Policy Research, SEWA Union and Institute of Social Studies Trust.

Having worked on several research projects in her career, data has been a steady friend for Shrayana. She says that during her years collecting data across different states in India, her conversations with the women about the Bollywood icon Shah Rukh Khan gave her insights into their lives and desires.

Also read: Celebrity Crush: Exploring Sexuality And Finding Refuge In The Realms Of Fantasy

The book, in Shrayana’s own words, is about women and Shah Rukh is but a “research tool”. ‘Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh’ explores the lives, works, economic, social, political and the personal standings and struggles of diverse groups of women divided by class and caste identities but brought together in their love and search for Shah Rukh. It is an attempt to take account of a struggle for freedom as well as a search for the intimacy of Indian women, that Shrayana documented over 15 years.

In an exclusive chat with the author for feminisminindia.com, Shrayana Bhattacharya talks about women and work, fandoms and small rebellious acts of self-expression and Shah Rukh.

You must have by now got tired of answering this, but we cannot resist but asking: What has been your journey with Shah Rukh Khan?

Shrayana: (laughs) So I remember I was very young. I must have been 12 years old, in Kalyani (Nadia, West Bengal). My grandmother’s house was right next to a cinema hall and I has gone to the movie hall to watch ‘Baazigar’ (1993), which I think is a very bad introduction movie for a child. Before that, I had never seen SRK anywhere else and I was completely bowled over by him, despite the extremely harmful traits and characteristics that he embodied in the movie. I came back and I used to dance to all the songs, and that’s how it began.

But I remember it was ‘Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa’ that made me the nutty fan that I am now. I think the movie was beautiful in the way it portrayed rejection and disappointment without it being a “hyper-moralistic” statement.

For me, while I was doing research for the book, the image and idea of Shah Rukh Khan grew and changed. I no longer see him as just a superstar, but as a person who brings together the imaginations of different women of the country. So now when I see him, I just don’t see him, but all the women I have spoken to, their excitement, their disappointment, etc.

Something that you have talked about at length in your book is the “small acts” like taking cutouts of Shah Rukh from magazines and newspapers or being vocal about liking him as a young woman. When do you think these “little acts” started to mean more, and encompass a bigger narrative of claiming agency and space in a society that historically and systematically denies you autonomy?

Shrayana: This is interesting because it did not occur to me until much later while working on the book. I realised that irrespective of where you came from, your social and economic position in the society, your privileges, a woman saying out loud that “she likes the way a man looks or behaves” makes families paranoid. In a patriarchal society such as ours, where we are so obsessed with the “sexual purity” of a woman, the idea of her claiming sexual agency is a nightmare. The act of putting up that poster on our walls, watching Shah Rukh movies, and claiming we like him might seem very banal, but it is an act of women expressing their sexual agency and romantic autonomy. And that is a huge thing in a country where only 5% of the women get to choose their own partners.

Especially for the women who came from marginalised backgrounds, to hold on to the autonomy that claiming their love for Shah Rukh gave them was indeed remarkable and extremely important. The book is a homage to the everyday minute struggles that women have to deal with on a daily basis just to claim space, even in their fantasies. And I think we live in a country where women’s fantasies really scare people. Through the women I interacted with over the course of writing, I realised that there was tremendous rebellion in these fantasies. Fandom is not just a foolish act of worship, but a way for women especially to assert more freedom and imagination within an extremely clustered masculine environment.

Fandom when it comes to men liking sports or players is perceived very differently as opposed to people being fans of Bollywood stars or personalities. The BTS fandom (army) for example is looked down upon because it mostly consists of women. It is termed as amateur and silly. What are your thoughts on this?

Shrayana: I think that as a society we are frightened of women claiming joy and fun. There is something about women’s loud laughter that makes society uncomfortable. I mean, there are court judgments as recently as 2020 about what is the normative behavior for women in cases of assaults, harassment, and rape. Society has a script of womanhood, where a woman is supposed to be somber, silent, supplicant, ideally within the four walls of her house and she can only have fun, laugh, and smile when the family is doing the same.

Public spaces too, make sure to restrict women’s access and autonomy. Unlike women, men are sanctioned a good time because they will be more responsible in not disrupting incumbent societal structures and caste hierarchies. Meanwhile the fear is that women might mingle with and become friends with people outside acceptable norms and that will start changing the shape of society.

I believe that women being economically independent, and asserting their own pleasure, is the most sustainable path toward our country’s social script changing. When I was in the process of writing the book, people would ask me what the book was about, and I would say it was about women and a look at their lives while using Shah Rukh as a tool and I faced a lot of judgment for that. While I know that I have the privilege to say “to hell with the judgment!”, I know that there are others who are judged and become silent about what gives them joy. Underneath everything, there is a deep sense of paranoia as to what will happen if women decide to speak their minds. A larger thought that I discovered while talking to the different women is that if public spaces were more accessible to women, most of them would not marry or would marry very differently and that would completely disrupt the structure of society and capital. In conclusion, I would say that this fear of “women having fun” is very socio-economically propelled.

Underneath everything, there is a deep sense of paranoia as to what will happen if women decide to speak their minds. A larger thought that I discovered while talking to the different women is that if public spaces were more accessible to women, most of them would not marry or would marry very differently and that would completely disrupt the structure of society and capital. In conclusion, I would say that this fear of “women having fun” is very socio-economically propelled.

The cover of the book is very interesting and while Shah Rukh’s name is there, you see but a tiny glimpse of him in what I presume is a wallet. How did that come about and what was the thought behind that?

Shrayana: The image is representational of how I think Shah Rukh represents three important things that are key to the gender crisis in the country – One is that he is the metaphor for women having money to do what they want to do. Two, he is also a metaphor for pleasure from a woman’s point of view. And the third is escape: an escape from very harsh realities. The person who designed the cover said he was inspired by a girl whom he met on the Delhi metro. The girl had a wallet with a picture of Shah Rukh Khan slightly hidden picture, presumably fearing the judgment we were just talking about. That is what led us to the decision of making it the cover of the book.

When did this idea of using Shah Rukh as a research tool come to you?

Shrayana: It was quite abrupt. I saw that talking about Shah Rukh with people allowed me to take a deeper look into their lives in ways which a regular research questionnaire wouldn’t have allowed me to. The way that talking about Shah Rukh Khan helped the women I spoke to open up to me and helped me open up to them was something different. Talking about Shah Rukh basically built a bridge that did not exist to begin with.

Pleasure as a tool of solidarity and communication, and as a language is something that we should claim and own. You know there is a kind of legitimacy I feel that is given to men’s interests, which I think women’s interest never gets. Which is why I feel Shah Rukh becomes an anchor for the book’s research, because the women I spoke to felt very powerful while talking about him.

We know that data on women and other marginalised communities, is limited. And this problem has only aggravated over the past couple of years, with respect to pandemic inequality and vaccine trials, etc. The book very succinctly weaves gender data into the narrative. What was the thought behind structuring the narrative in that manner, as data is typically looked at as something ‘boring’?

Shrayana: For me, the book is a love letter to the women of the country. And I realised that this letter will be incomplete without very clear communication evidence on the structures of our society that make it difficult for women to make the simplest transactions. I could not do it without giving the real and honest picture through available data. It is a story about Indian women and you cannot tell the story without putting data out there. I wanted young people, especially young women, who want to study data to not be scared of it.

I also feel that there is an elite class of people in our country who feel that women have become “too independent”. And I wanted a vision correction there and wanted them to understand that the reality is far from it.

While reading the book, it was very interesting to find out that Shah Rukh is one of the most searched actors in conflict countries and regions. Could you expand your thoughts on the same for us?

Shrayana: Honestly, I don’t think I know what the reason behind this data is. What I do know from my research and reading other people’s works is that so many people who are in conflict-laden and precarious situations really relate to him. I don’t have an answer to it but is a very interesting statistic. And I am hoping someone will study this.

How do you think the discourse around the icon and idea of Shah Rukh Khan changed in contemporary times, especially given the immense communal pressures rising day by day? And what do you think claiming him would mean in this context?

Shrayana: In the book, you will notice that in the conversation with the women, until the CAA-NRC protest, his religion just never came up. The only time it comes up is when one of the women in the book, who is this young Muslim woman feels let down by his silence on the whole issue. I think he is slowly becoming this precious scarce commodity because of his identity as well as the space that he occupies and the person that he is.

I think it can be said that while being this huge cis-heterosexual icon, he also seems accessible to people of other sexual and gender identities. Do you have any comments on that?

Shrayana: You know one of the things I have realised over the course of time while working on the book and otherwise is that the Shah Rukh Khan is huge amongst members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Someone I had met said that they felt comfortable coming out to their parents, because of the way Shah Rukh would own up to the criticism for not being “hypermasculine”. I think what Shah Rukh and the romance he embodies portrays is a complete retirement of tactics and giving in to imagination.

Also read: FII Interviews: Kiran Manral, Author Of ‘Rising: 30 Women Who Changed India

You have spoken to so many women over the last few years, if you were to sum it up, what would you say is that one thing that binds all their narratives together?

Shrayana: Most of the women that I interacted with while working on the book are trying to move towards and fighting for little feminist goals without even knowing what feminism is. And each one of them is doing it in their own ways. What I think binds all of them together is that they are partaking in these intimate revolutions, changing the way society looks at women on a daily basis by doing very simple things. There are these smaller and invisible acts of resistance amongst the women that make them very powerful.

Author’s note: When we interviewed Shrayana, we still did not know if the book had reached Shah Rukh Khan and if he had read it yet. In the last week of April, we got to know that the book has found its place in his library and Shrayana did meet him at his house in Mumbai. In Shah Rukh’s own words he is thankful for being put to “some good use”. You can find the link to the book here.

About the author(s)

Shriya is a former student of literature and a multimedia journalist with an interest in sports and human rights. She can be found watching Shah Rukh Khan movies or listening to Ali Sethi and 90s Bollywood songs. She enjoys a good cup of black coffee multiple times a day and is often compared to 'Casper, the friendly ghost'.