Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for May, 2022 is Gender at Workplaces. We invite submissions on the many layers of this theme throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly refer to our submission guidelines and email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

Matrimonial advertisements through the years have charted a timeline of the changing value and image of a woman. From a primarily homely demand from a bride, the market has grown partially towards the educated and working kind. Once married, demand precedes choice in producing an offspring.

Reproducing without the seal of marriage and retaining social status is an oxymoron, unless you already come from immense social capital. It is an intensely complicated game of monopoly, where you never really win. Beyond the urban and its progressive need for financial independence, the suburbs and grassroot economic structures often make it essential for the women of the household to cross their thresholds and earn a living.

With menstruators populating the workforce in both organised and unorganised sectors while holding the reproductive system capable of producing progeny, let us look at the status of maternity benefits in this country.

Maternity benefits in India: A timeline of laws

In pre-independence India, the first legislation that formally addressed the need for provisions related to childbirth in the workspace was set into motion in the Maternity Benefit Act (1929). Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, N.M Joshi and M.K Dixit drafted the bill, and thereafter, defended it in the assembly.

Babasaheb emphasised the need for maternity benefits and the responsibility of the employer and the State in funding the same. When the Maternity Benefit Act was tabled in the Bombay Assembly (1928), he argued that, “…it is in the interests of the nation that the mother ought to get a certain amount of rest during the pre-natal period and also subsequently, and the principle of the bill is based entirely on that principle. That being so, Sir, I am bound to admit that the burden of this ought to be largely borne by the Government.”

But subsequently, he also reflected that the onus falls largely on the employer. The bill was majorly pushed forth by the cotton factory workers’ conditions in Bombay, which employed women on a large scale, but failed to recognise their reproductive rights.

Pre-natal leave can be availed for 8 weeks. Maternity leave reduces to 12 weeks, from the third child onwards. A very important update grants 12-weeks leave for adopting mothers (provided the adopted child is below the age of 3 months) and commissioning mothers (individuals availing surrogacy services). Also, according to the 7th Pay Commission, a government employee is eligible for a total of two years’ paid leaves, or 730 days, under parental leave provisions, till the ward is 18 years of age. One of the most important amendments that came in the year of the controversial Transgender Persons Bill of 2019, is the Transgender Non-discrimination clause. The clause explicitly prohibits discrimination in employment and ensures that trans individuals are protected by the Maternity Benefit Act

In independent India, the revised International Labour Organisation’s Maternity Protection Convention, 1952, finally kickstarted the delayed enactment of “humane” working conditions for working women in India. The Maternity Benefit Act of 1961 was brought to force in independent India, following the route laid by the pre-constitution legislations.

14 years after our independence, we finally felt the need to protect the rights of a woman in labour. But as the anthem of the hapless goes, “Der ae par durust ae” (Better late than never). The Act extended to factories and governmental bodies but provided no such relief in agriculture or small scale industries.

It laid down a six-week time period of rest for new mothers. No employer could hire or make an existing employee work during the six weeks immediately following the day of her delivery or her miscarriage. It was also stated that no claims can be made until and unless the woman has been employed by the institution for less than 160 days.

From the addition of rules in 1963, bringing circus and mine industries into the ambit of the Act, to the addition of INR 3500 as medical expenses, the Act of 1961 has been amended a few times. The latest amendment was made in 2017, that grants paid maternity leave for 26 weeks, eligible for organisations with a minimum of 10 employees.

Pre-natal leave can be availed for 8 weeks. Maternity leave reduces to 12 weeks, from the third child onwards. A very important update grants 12-weeks leave for adopting mothers (provided the adopted child is below the age of 3 months) and commissioning mothers (individuals availing surrogacy services). Also, according to the 7th Pay Commission, a government employee is eligible for a total of two years’ paid leaves, or 730 days, under parental leave provisions, till the ward is 18 years of age.

One of the most important amendments that came in the year of the controversial Transgender Persons Bill of 2019, is the Transgender Non-discrimination clause. The clause explicitly prohibits discrimination in employment and ensures that trans individuals are protected by the Maternity Benefit Act.

Also read: Maternity Benefits Must Be Extended To Tackle Child & Maternal Malnutrition

Loopholes in the legal provisions

Despite the fact that these protections are in place for women in service, can an employee be fired right before the employer has to grant them maternity benefit? There is no provision, even after the latest amendment of 2017, that can ensure that a pregnant employee will not be dismissed.

There is a small clause that penalises this with a fine of 2,000 to 5,000 INR, if they fail to pay the amount the pregnant person is owed as per the Maternity Benefit Act. But does it mean that we can keep a check on the fair employment of pregnant women or people of “child-bearing age”?

Often women “choose” to take a break from their careers to plan their pregnancy. Sometimes that break drags longer than they had planned to. Sometimes, they go back to their work feeling out of touch or chained to the identity of a slacker. Appraisals and promotions take place based on current performance, so, an individual on maternity leave misses many opportunities they could have otherwise taken. Maternity benefits and provisions are well-drafted in India. But when workaholic corporate culture mixes with gender roles, with a misogynistic cherry on top, it becomes a cocktail difficult to down

This is the first of the many loopholes in the Act, which reflects the moral, gendered attitudes of our society. Post the 2017 amendment, more than 40 per cent of the employers preferred hiring male candidates, stating that this would be their choice with or without the government paying for 7 weeks of the benefit. For medium or small-scale industries, it is an undeniably hefty cost. Merit is already a replaceable commodity in the existing market, so the threat of cost to the company is too big an ask for a good Bechdel Test score. The informal sector is seeing the worst effect of this legislation.

It is also important to mention that the eligibility clause of more than 10 employees keeps a lot of small-scale industries and start-ups out of the bracket of maternity benefits. Even though it is true that the smaller the industry, the more difficult it is to bear the employee cost, the government should have special aid for these organisations, to ensure the safety and health of the pregnant employees involved.

Maternity benefits, gender roles and ‘girl bosses’

Women’s progress in India and its relevant success has been deeply capitalist. “Girl-bosses” taking over the corporate world has been seen as a victory of sorts. Even as women populate the organised and unorganised workforces, with their unique patterns of exploitation, the burden and boon of ovaries demand specific labour.

Private companies are not exempted from this Act, but women employees are often afraid to ask for their rights. The ecosystem of fear nourished by the hustle-culture considers it to be a heroic feat of professionalism if a worker is at her desk till her water breaks. With the many start-ups and smaller corporates in the economy today, such instances are not uncommon, in the absence of a regulatory body

Families expect their trees to grow. From bearing to rearing, motherhood is a responsibility that is emotionally and physically bound to women. To help sustain normativity, the lack of paternity leaves in India contains a woman’s labour to her motherhood. India’s federal and state government allows a fortnight’s leave for its male employees, at the time of delivery or anytime in the following six months. This assures that women continue to be the primary care-givers.

Often women “choose” to take a break from their careers to plan their pregnancy. Sometimes that break drags longer than they had planned to. Sometimes, they go back to their work feeling out of touch or chained to the identity of a slacker. Appraisals and promotions take place based on current performance, so, an individual on maternity leave misses many opportunities they could have otherwise taken. Maternity benefits and provisions are well-drafted in India. But when workaholic corporate culture mixes with gender roles, with a misogynistic cherry on top, it becomes a cocktail difficult to down.

Private companies are not exempted from this Act, but women employees are often afraid to ask for their rights. The ecosystem of fear nourished by the hustle-culture considers it to be a heroic feat of professionalism if a worker is at her desk till her water breaks. With the many start-ups and smaller corporates in the economy today, such instances are not uncommon, in the absence of a regulatory body.

Unions, though growing feebler every day, keep a check on factories and mines. The Human Relations Department is the closest yet also the most farcical body designed to keep a check on corporate ethics. With such strong legislation addressing this issue, Indian women are still struggling to negotiate between professional labour and reproductive labour.

While women in Beed (Maharashtra) are getting their uteruses removed for better employment prospects, urban women are skirting the conversation around maternity benefits. The raised period of 26 weeks has been formalised to help child-bearers take a proper break and then come back to work.

Workers must be periodically sensitised and updated about the provisions made available to them by law. It is even more important to know the loopholes used by employers, both professional and familial. Once educated about their choices and rights, pregnant individuals will be able to make informed decisions about their life, away from the traditional gender expectations.

Also read: The Biological Is Political: Menstruation, Maternity & Women’s Employment

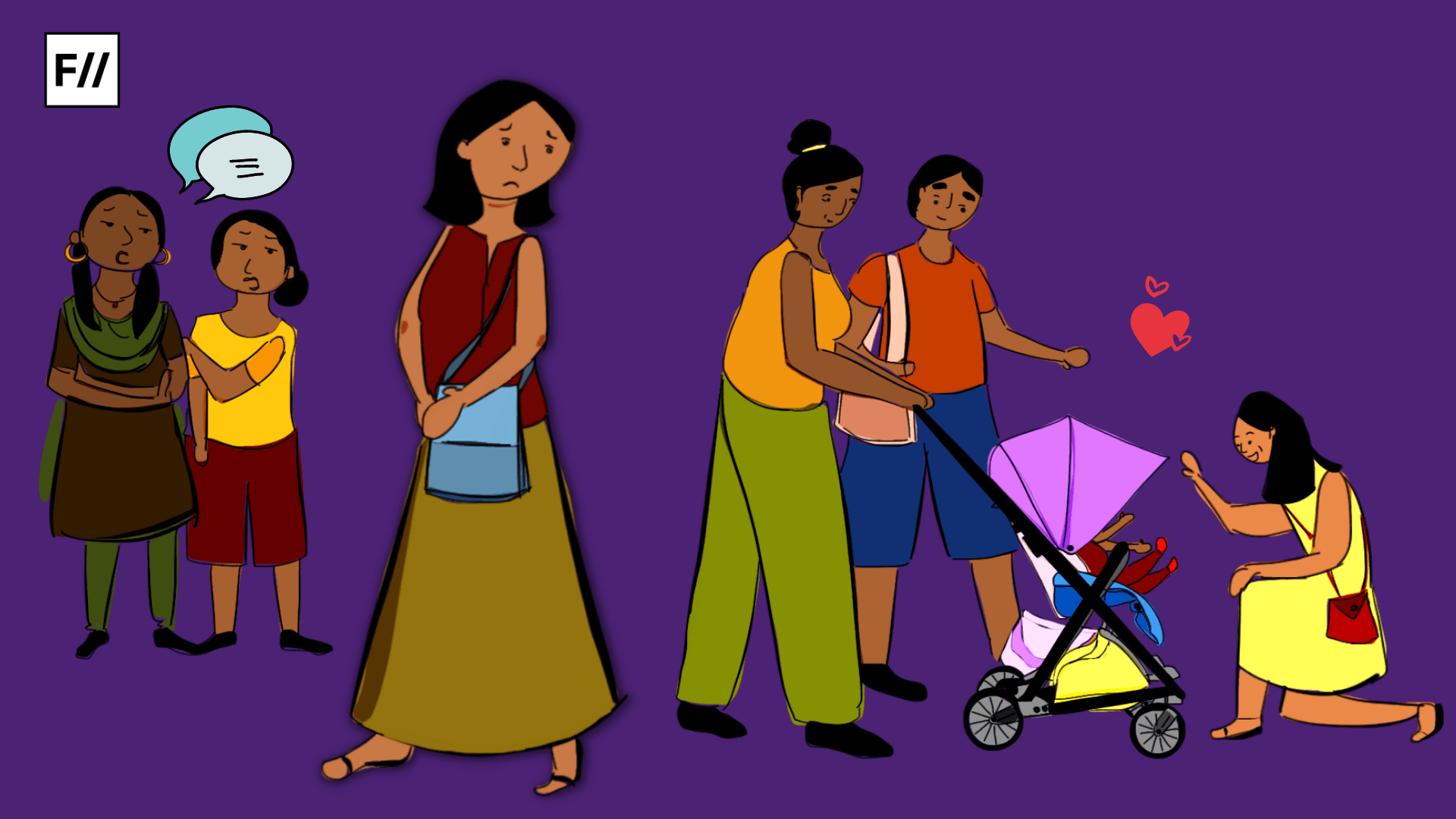

Featured Illustration: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo