It was over a phone call that an acquaintance who is pursuing her higher studies at the University of Delhi asked me, “So in which year did you complete your class 12th? Did you take any year gap?” The question had no context to the conversation we were having, so I tried to dodge it, “Many times, people are going through certain situations”. “Yes, different people have different difficulties”, she answered. She had no idea that I was a first-generation learner. Her generalising of ‘difficulties’ triggered me.

However, I did not talk about my discomfort or my journey till the day the Women’s Development Cell of Miranda House, DU, with the support of the Centre for Women’s Studies, New Delhi, published a report. The report is named ‘First Generation Learners: Navigating University Education and Culture’.

We live in a country where even the best academic spaces have many structural flaws which are not yet addressed, or if they are, the approach is no more than a tokenistic agenda. The inequality in education from the perspective of first-generation learners has drawn little attention. This makes first-generation learners spend half or sometimes more of their academic journey in self-doubt, because of the privileged idea of ‘merit’, in addition to the learners’ systemically-created lack of social and cultural capital.

In the recent past, through my observation and interaction on a personal level, I came across many people from marginalised identities, be it on the basis of caste, class, gender, region, religion etc., who share a similar sense of trauma, self-doubt, and feeling of non-belongingness in the university space.

We live in a country where even the best academic spaces have many structural flaws which are not yet addressed, or if they are, the approach is no more than a tokenistic agenda. The inequality in education from the perspective of first-generation learners has drawn little attention. This makes first-generation learners spend half or sometimes more of their academic journey in self-doubt, because of the privileged idea of ‘merit’, in addition to the learners’ systemically-created lack of social and cultural capital.

Before we understand the diverse and homogeneous yet less addressed community of FGLs or First Generation Learners, let us understand who all can be put under this category. According to the above-mentioned research paper, FGLs are the individuals who “might or might not have parents or other elders in the family who went to school; however, to qualify as an FGL at the university, it is imperative that parents or other elders in the family have never had the experience studying in the University”. These FGLs have no familial knowledge of university life; each has a unique journey of navigating and surviving university education.

Are they the ‘Disadvantaged Learners’ or is it the failure of the university space for not being inclusive enough?

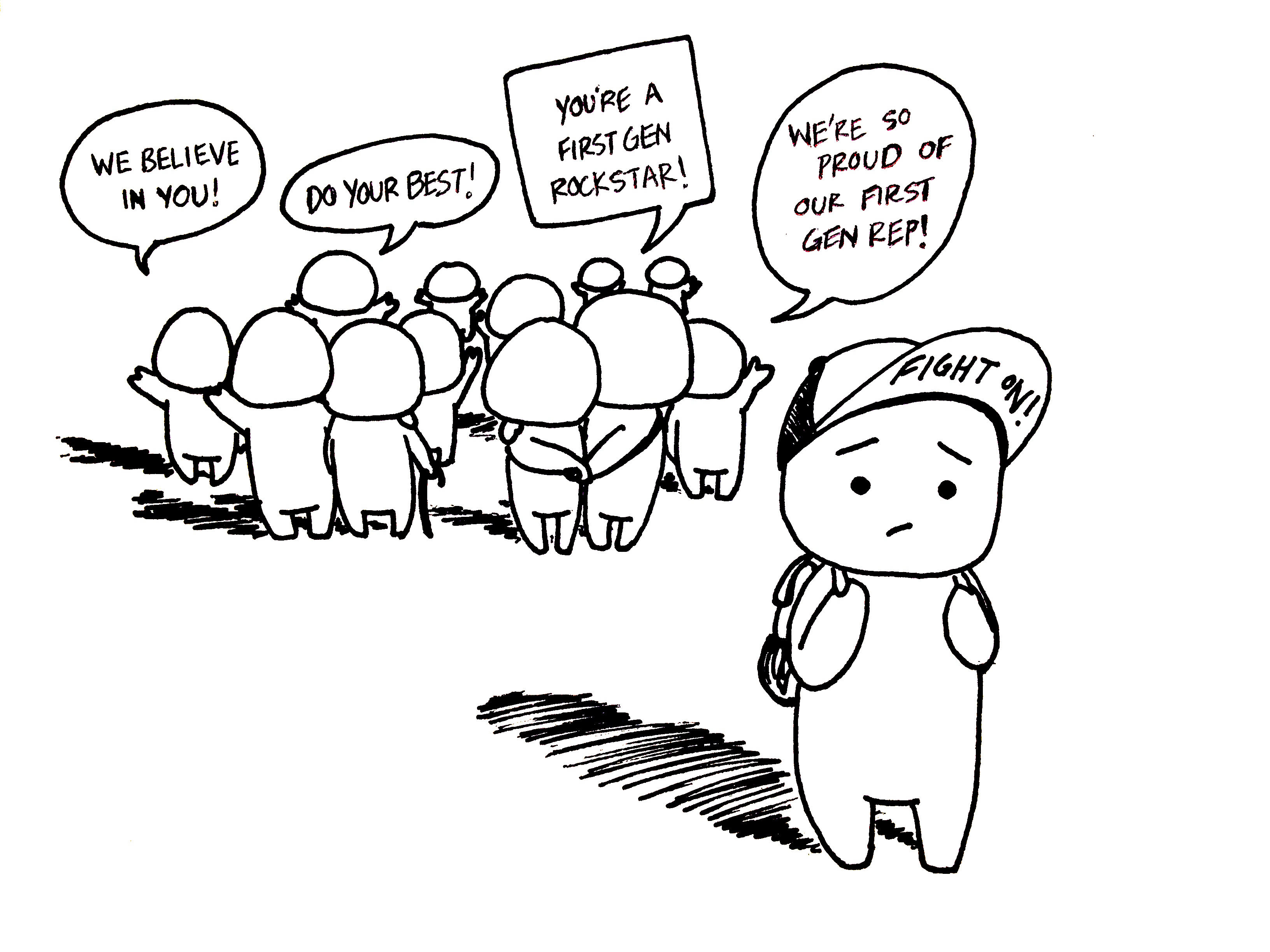

First-generation learners are often seen as ‘disadvantaged learners’; the connotation of ‘pity and encouragement of a certain kind which comes from the gaze of privileged is an example of the mainstream behaviour of this country. The influence of social differences on education has also been observed by Moloy Bhattacharya, who noted that aspects of caste and class come to define the educational experience in India.

In states like Bihar, the educational conditions are unique. According to the latest report of Dainik Bhaskar, except for Patna University, students have to invest five years for an official three-year Graduation course and four years for a two-year Post Graduation course. The new regulations of the University Grants Commission (UGC) provide for ensuring at least one teacher for every ten students at the postgraduate (PG) level and one for every twenty-five students at the undergraduate (UG) level. As reported, there are colleges in Bihar with 3000 to 4000 registered students and three-four teachers. At Magadh University, there are less than 2,000 teachers for altogether two lakh students.

Before we understand the diverse and homogeneous yet less addressed community of FGLs or First Generation Learners, let us understand who all can be put under this category. According to the above-mentioned research paper, FGLs are the individuals who “might or might not have parents or other elders in the family who went to school; however, to qualify as an FGL at the university, it is imperative that parents or other elders in the family have never had the experience studying in the University”. These FGLs have no familial knowledge of university life; each has a unique journey of navigating and surviving university education.

In my lower-middle-class OBC family from Bihar, one or two of the family elders are graduates. However, the other kids in the family or I have never had prior information, data or experience of university spaces. The reason is that the college was not structurally a college with the ecosystem and the opportunities one imagines a university to possess. Secondly, they could never go to college regularly as they had to support the economic system of the family from an early age. One can imagine the lack of social capital I had from this incident.

Similar is the case with the family of Mithilesh Kumar, who hails from the Nawada district of Bihar. He also identifies as a First Generation Learner on similar experiential grounds.

When I cleared the cutoff of the college, which boasts itself of holding NIRF rank 1 for the last consecutive five years. my concern was, “What would people back at home think of this?” The name of the college I finally graduated from, ‘Miranda House’, was funny to my ears because it sounded like the soft drink ‘Mirinda’. It was not just the resemblance with the name of the soft drink but the lack of information. These chains of events and circumstances, which continue to date, make me observe myself as an FGL without any dilemma.

When I cleared the cutoff of the college, which boasts itself of holding NIRF rank 1 for the last consecutive five years. my concern was, “What would people back at home think of this?” The name of the college I finally graduated from, ‘Miranda House’, was funny to my ears because it sounded like the soft drink ‘Mirinda’. It was not just the resemblance with the name of the soft drink but the lack of information. These chains of events and circumstances, which continue to date, make me observe myself as an FGL without any dilemma.

However, the “lack of information” among the family and the First Generation Learners themselves is often mocked as incidents of ‘being backward’ or ‘dull’. The system creates paucity in the academic background of first-generation learners, making them go through a process which is often fraught with unpleasant experiences.

In my lower-middle-class OBC family from Bihar, one or two of the family elders are graduates. However, the other kids in the family or I have never had prior information, data or experience of university spaces. The reason is that the college was not structurally a college with the ecosystem and the opportunities one imagines a university to possess. Secondly, they could never go to college regularly as they had to support the economic system of the family from an early age. One can imagine the lack of social capital I had from this incident.

Every First Generation Learner has their own unique journey, owing to their unique social location. But they share a common set of anxieties and hesitations in approaching university life.

In 2022, the addressal of the struggles of FGLs in the timeline need not be academically romanticised, for it is a crucial issue whose solution has been postponed for long. Reports have been published about how in 1990, the upper-caste student riots during Anti Mandal Commission in Delhi University believed that the reservation was ‘de-cognition of merit’ and was hence bad for the country. A student named Rajeev Goswami was so strong-headed and rigid in his beliefs that he self-immolated himself in protest.

People recall how back then, in their PG days, many students and even some teachers believed the OBC reservation would malign the educational institution. Journalists have written, “On a personal level, I didn’t join the anti-Mandal agitation because I felt that my job was in danger…A bigger challenge came when I became a journalist. My job took me to nook and corner of the country…I saw the real India…And I became an ardent supporter of reservations for SCs, STs and OBCs”.

Suraj Yadav, the grandson of former CM of Bihar BP Mandal who scripted the original Mandal Commission, stated, “I was one of the few people who spoke in support of the government”, referring to his solidarity towards the OBC reservations. He then went on to say how he had sensed the tension building between his upper-caste friends and his ‘backward friends’.

I often wonder, will the First Generation Learners from the communities whose educational rights have been protested against in the university be made to feel welcomed enough? And will they be welcomed enough to make FGLs forgive, if not forget, the ancestral trauma? If yes, when?

I often wonder, will the First Generation Learners from the communities whose educational rights have been protested against in the university be made to feel welcomed enough? And will they be welcomed enough to make FGLs forgive, if not forget, the ancestral trauma? If yes, when?

When I first learnt that one of my favourite people from Bollywood, Mr Anurag Kashyap, who in this era of the BJP government at the Centre, very strongly advocates for artistic freedom and the sustenance of the democratic nature of freedom of expression, was active during the Anti-Mandal riots against OBCs, I was more disappointed than shocked. He did offer his ‘unconditional apology’ for participating in the anti-Mandal protests as a ‘teenager’. I truly believe in the learning-unlearning trajectory and evolution of human beings, but this thought never leaves my mind — for his college batchmates from marginalised identities and who were of the same age as his, will the personal experience that they had with Anurag Kashyap become mentally distant to view him as the ‘liberal person’ the world sees him as! What about the trauma that would stay with them?

Challenges faced by first-generation learners

The challenges faced by first-generation learners range from linguistic basis to having difficulties in socialisation and fitting into the in-trend university aesthetics. Offline, this would include being a ‘cafe person’ or online; it would be seen in terms of visual Instagram aesthetics).

When I first learnt that one of my favourite people from Bollywood, Mr Anurag Kashyap, who in this era of the BJP government at the Centre, very strongly advocates for artistic freedom and the sustenance of the democratic nature of freedom of expression, was active during the Anti-Mandal riots against OBCs, I was more disappointed than shocked. He did offer his ‘unconditional apology’ for participating in the anti-Mandal protests as a ‘teenager’. I truly believe in the learning-unlearning trajectory and evolution of human beings, but this thought never leaves my mind — for his college batchmates from marginalised identities and who were of the same age as his, will the personal experience that they had with Anurag Kashyap become mentally distant to view him as the ‘liberal person’ the world sees him as! What about the trauma that would stay with them?

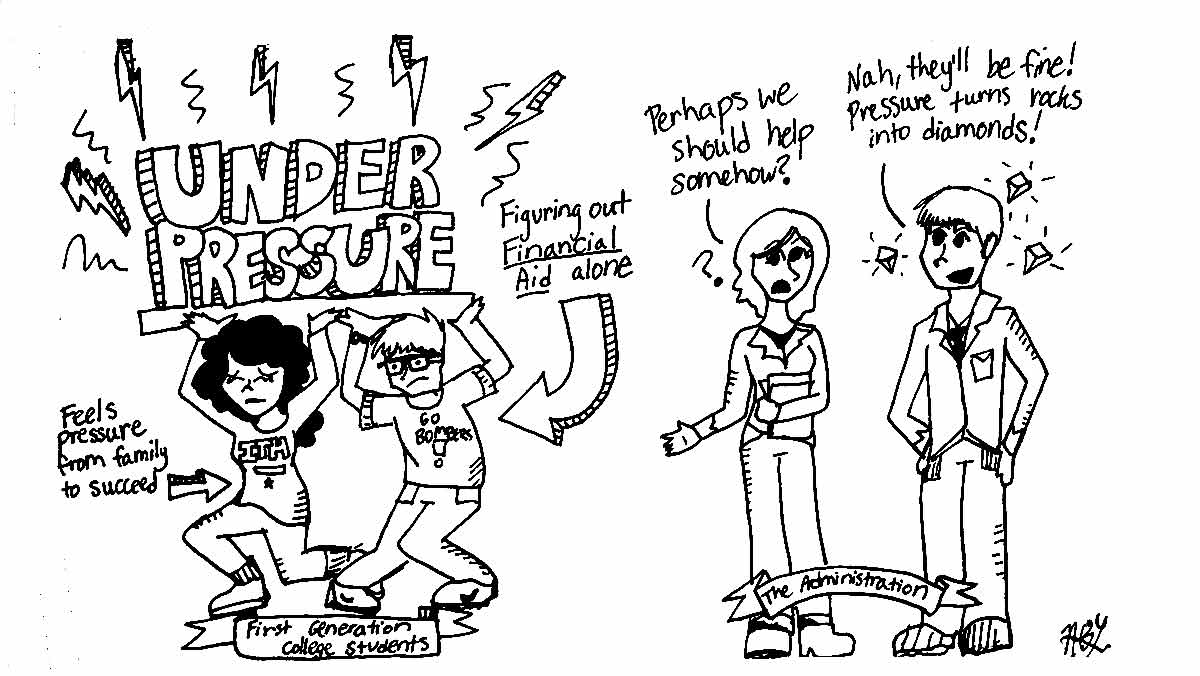

The various reasons which have emerged as the findings that limit the FGLs in the university space alongside their percentage are staggering. They include 44% due to inferiority complex, 22% due to language barrier, 18% due to atmosphere of discussion and 15% due to the technical issues. The cultural societies such as Western dance society and music societies on the campus have an audition process. The students who have some kind of prior training and exposure are considered “skilled” and confident enough to get through them. Data states that about 35% of FGLs were not able to join any college society.

First-generation learners also experience a lack of affordable accommodation and enough scholarship schemes as a barrier to sustaining in the city and the university. 47% FGLs had an annual income of less than two lakhs. The amount of money they have to spend on travel has an impact on their mental health as well. Psychological impacts include feeling lonely in the city or lacking a sense of close-knit community feeling. This is often accompanied by “pressure to do better” because no one in the family has reached ‘this far’.

Due to poor financial status, first-generation learners don’t have the leverage to ‘take a break’ and be able to visit their native places. Not every family or native place is a ‘safe space’, but I have observed some of my friends who identify as FGLs admit a needed break to go back to the place they came from, however ‘tiring’ or ‘triggering’ it might be. We need to stop here and question, for such individuals, is the university space structurally just a case of ‘worse-over-worst’ or vice versa!

Also read: Remembering B P Mandal: The Imperative Voice For The Cause Of OBCs

It is due to this that many times they drop out of college or stop taking regular classes. The reason for my gap year resonates with all of these.

Had the university space been successful in sensitising itself for the First-Generation Learners and being prepared to receive them, the generalisation of their ‘difficulties’ would not have happened, or if it did, they would have felt confident in their journeys to claim it unapologetically. It is unfortunate that FGLs have to oscillate between the state of owning their narrative and being viewed through the privileged understanding of ‘academic merit’.

Also read: Tarabai Shinde: Breaking Caste & Patriarchy Glass Ceilings | #IndianWomenInHistory

Featured image source: Women and Children First