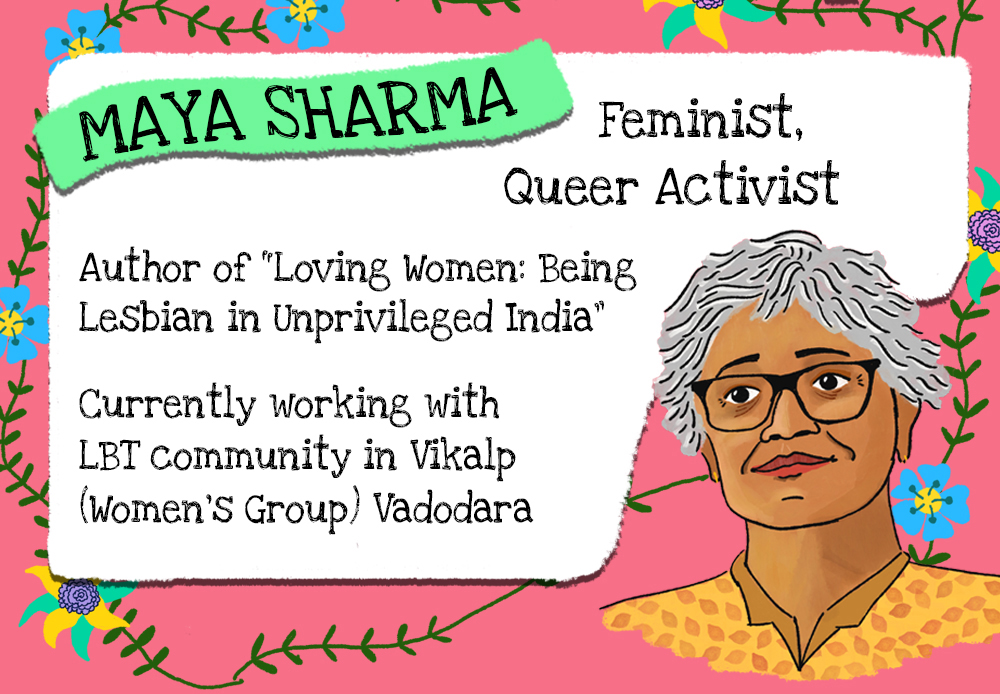

Maya Sharma’s book, Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India, is a collection of ten stories of women from some of the most economically unprivileged strata of the country. The stories pertain to their intimate companionships with other women and their struggles in negotiating their desires and their love, alongside the structures of heteronomous family, economic disparities and binding patriarchy.

By bringing in the lenses of both class and sexuality to capture the life stories of same-sex love among underprivileged women, Sharma makes significant contributions to queer studies in India. She successfully challenges the dominant imagery of the homosexual subject in India — as urbane, westernised, college-educated and English-speaking middle class, that a sole focus on pride parades, gay queer collectives and gay bars seem to project.

More importantly, she dismantles the idea of queer behaviour as something rare, pertaining to only a ‘minuscule’ minority. Sharma writes that despite the apprehension of not being able to find and identify subjects, everywhere she enquired, people knew of women who loved other women. Thus, even though patriarchal control of sexuality has a pervading presence in the life of women, which recognises their sexuality only in relation to men, the queer affinities narrated in this book suggest how women effortlessly develop intimacy with women as a way of coping, as well as rebelling against the patriarchal control, both silently and explicitly.

Maya Sharma’s book, Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India, is a collection of ten stories of women from some of the most economically unprivileged strata of the country. The stories pertain to their intimate companionships with other women and their struggles in negotiating their desires and their love, alongside the structures of heteronomous family, economic disparities and binding patriarchy.

Secrecy, denial, conspiracy, lies spoken and unspoken, heard and unheard: The many struggles of same-sex love.

The pictures that Maya Sharma paint, however, is far from rosy, and elements of resistance should not suggest a romanticised narration of the struggles of these women. Maneka and Payal, aged 15 and 16, ran away from their home together and were later found and brought back home. The candid utterance of Payal of being in love and wanting to stay together not merely disrupted societal norms and expectations; it also became a point of resentment for Maneka, who accused her of maligning her image. This eventually distanced them. One can’t help but feel a sense of frustrating defeat at the hands of “family, secrecy, denial, conspiracy, lies spoken and unspoken, heard and unheard” that work, besides outright censure and violence, to keep women in their places.

Hasina and Fatima’s is another such story. Hasina refers to Fatima, sometimes as a man and at others, a woman, one sees a glimpse into the gender fluidity in the lived experiences, existing alongside and sometimes as a way of coming to terms with fluid sexual experiences of these women. It is, however, also a tragic story, wherein the objection of the society, including one’s own children, tests a woman’s will to find joy and companionship with another woman.

By bringing in the lenses of both class and sexuality to capture the ‘life stories of same-sex love among underprivileged women, Sharma makes significant contributions to queer studies in India. She successfully challenges the dominant imagery of the homosexual subject in India — as urbane, westernised, college-educated and English-speaking middle class, that a sole focus on pride parades, gay queer collectives and gay bars seem to project.

The story of Hasina and Fatima is representative of the love shown in the book in general — struggling against “norms and pressures of marriage, traditional family structures and daily struggles of material survival”, they find with each other a relationship of love, mutual support and interdependence that blurs the set lines between sexual relationship and emotional bonds.

Shobha, an acquaintance of Manjula and Meeta, writes, “This is a good thing between two women, I mean a relationship like that between husband and wife. Two women can support each other physically, emotionally, and financially. If there were more such relationships, men would not know what to do! In a relationship between women, one will not eat after the other has eaten, or get up early to do chores and go to sleep late finishing chores, or meekly obey the other without question, as it is in man-woman relationships.”

Friendship, intimacy, resistance: a lesson in political lesbianism?

Sabo and Razia’s story demonstrates the dual aspect of same-sex love — intertwining the narratives of struggle, hardship and censure with those of courage and hope. Sabo worked with Maya and was an independent, practical and stubborn woman. Her relationship with another woman, Sharma writes, was a “mysteriously alluring chink in Sabo’s otherwise dry armour” to investigate, which the author travelled to Razia’s village.

Razia and Sabo’s relationship progressed, and in fact strengthened, through a long period during which they underwent forced marriage, domestic abuse, multiple pregnancies and immense mental trauma. These two women looked forward to marrying their children together, which would bind them into a socially legitimate bond, allowing them to live together with greater ease, something that they, for the present, seemed to lack.

More importantly, she dismantles the idea of queer behaviour as something rare, pertaining to only a ‘minuscule’ minority. Sharma writes that despite the apprehension of not being able to find and identify subjects, everywhere she enquired, people knew of women who loved other women. Thus, even though patriarchal control of sexuality has a pervading presence in the life of women, which recognises their sexuality only in relation to men, the queer affinities narrated in this book suggest how women effortlessly develop intimacy with women as a way of coping, as well as rebelling against the patriarchal control, both silently and explicitly.

Sabo and Razia’s relationship carried on despite their marriages to other people, yet it lacked the feeling of being an extra-marital one. A lack of entitled possession that is inevitably expected in heterosexual alliances is striking throughout the book.

Mary’s story demonstrates this observation. Mary stayed in a love marriage and a highly abusive one for almost twenty years. She eventually escaped and started working in a woman’s organisation. Here she developed an intimate friendship with a woman. As they got distanced and her friend got involved with another woman, Mary couldn’t help but feel a melancholy loss. However, she also realised that the aggressive possession that exists in a conventional relationship had no space in theirs.

Caught between the “extreme emotions of jealousy and objectivity”, she realises that love is a flowing river which cannot be stopped. Coming to terms with this wisdom, Mary said that she wants to take care of herself and make herself reliant through her work.

The freedom of being oneself and on equal terms while being in an intense relationship with another has been acknowledged by several women in the stories.

The freedom of being oneself and on equal terms while being in an intense relationship with another has been acknowledged by several women in the stories.

Shobha, an acquaintance of Manjula and Meeta, writes, “This is a good thing between two women, I mean a relationship like that between husband and wife. Two women can support each other physically, emotionally, and financially. If there were more such relationships, men would not know what to do! In a relationship between women, one will not eat after the other has eaten, or get up early to do chores and go to sleep late finishing chores, or meekly obey the other without question, as it is in man-woman relationships.”

Of course, there are instances in which relationships between women take recourse to heterosexual imageries. Manjula and Meeta were often referred to by the phrase “miyan-bibi Jodi“. Meeta was clearly the dominant miyan in the relationship, riding a bike with Manjula in the carrier and watching over her like “a jealous lover”. Manjula reportedly never went to her village without consulting Meeta. Nevertheless, even in this relationship, there was a mutuality that rarely existed between man and woman.

Despite appearances, the author observed, “[I]t was clear that of the two, Manjula was the one who decided what, when and how much of their private life could be shared with an outsider.”

Through such observations, Maya Sharma’s book becomes a lesson in political lesbianism, lived and imparted beyond the world of academic debates, at the sites of intersecting dis-privilege.

This lesson exists not merely in the narratives of intimate sexual associations but even in the stories of courageous support and affection women extended to one another in unexpected ways. Guddi’s and Aasu’s story narrates how women’s groups themselves made a mockery of their relationship for being against the order of nature, society etc.

However, in the creation of the possibilities of their being together is the undeniable role of many women: Pushpa, who supported the idea of their independent existence outside of a heterosexual marriage and her readiness to pitch in material resources for the same; Guddi’s mother who did not violate her daughter’s wishes, even as she sought to ‘contain’ the situation through the route of ‘practical kinship’, and several others from the women’s organisation willing to support them in any manner possible, after initial hesitation.

The narrative of political lesbianism comes in an explicit way in the story of Juhi. Having gone through an abusive marriage, Juhi had gotten her daughters acquainted with the sexual alternative of being a lesbian and not merely supported but actively preached it. In her own words, “[A]ll my daughters are lesbians,” and in fact, “It is better and far wiser to be this way than to marry men”. She will support them, if they want to be with men, but “does not like the prospect much”.

In the course of talking about her life experiences, she remarks, “You know what? I think every woman is a lesbian at heart. What does it mean when women say, This is my best friend? Indirectly they are expressing their love for women. This is my personal opinion. Women love one another…”

Inter-sectionality in queer negotiations

Maya Sharma’s book goes beyond her observations on gender and sexuality. She goes on to capture a whole lot of other details from women’s lives which become essential components of their lived experience. A stark insight comes from the story of Vimalesh. Vimalesh consistently, throughout life, challenged the binary division of male and female imposed on different bodies and refused to feminise one’s appearance and to marry.

However, this struggle against dominant discourses didn’t extend to empathy with other marginalised groups. Being a Brahmin, Vimalesh exercises the prevalent “suspicion, scrutiny and phobia” towards the lower caste Harijans and chamars of her locality, thus choosing to hold on to power in one domain while resisting her powerlessness in the other.

Another set of difficulties came from the intersection between class and sexuality. Sharma writes of the deep ethical dilemma she experienced because of the deep class difference between her and her subjects, against which her class position gave her an automatic entitlement. However, she felt compelled to carry on the research because of two reasons: the company of working-class women who made her realise that her class position is precisely what enabled her to undertake the project of politicising and elucidating the intimacies of working-class women.

Secondly, the class-induced disparity in discourse, in fact, destroyed any sense of entitlement she unintentionally carried. As people from the lowest material position, the women interviewed didn’t have adequate access to terminologies and discourse of Queer movement. The usage of the term lesbian was also, in fact, fraught, since many of them didn’t use the term for themselves.

Only one woman, Juhi, openly used the term “lesbian. Many didn’t even acknowledge a sexual relationship, choosing to call their relationships “miyan-bibi Jodi”, “lived like husband and wife”, and very often, friendships. Sabo, when asked by her colleagues why she didn’t tell her of her same-sex love, retorted fiercely, “This was never a topic for conversation; no one made it an issue. How could I bring it up on my own? There was no forum for anyone to talk about women who loved women. Until I came into the single women’s group, and till I attended the Tirupati conference on women’s rights, I had not heard the word ‘lesbian’.”

The use of the word “lesbian” in the title despite its non-acknowledgement of the identity by the respondents themselves came from the broader goal of politicising the identity, which is so often “loaded with fear and embarrassment and prejudice…shrouded in silence”. It, however, is also laced with an important and instructive qualification. It shows how the lived experiences of same-sex intimacies often run into difficulty when juxtaposed against the single dominant trope of what it means to be queer.

Following the heterosexual/ homosexual divide that, according to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick fragments the western ontology, are several other binaries of secrecy/ disclosure; closet/ coming out; passing/ queering. As Neville Hoad mentions, this only reproduces the idea of a western enlightened queer subject whose primary identity comes from her sexuality. The reality often and more in some structural locations is more complex.

Steve Seidman has written in his book Beyond the Closet that queer subjects who belong to marginalised communities pertaining to race, class and gender experience their sexuality in very complex ways and much less in independence from their other form of identities. The tussle of living one’s sexuality takes on an even more difficult form since it necessarily proceeds as an inter-subjective process, occurring between different subjects we are related to, including family, as well between the different subjectivities that the subject herself embodies.

Maya Sharma’s account is an attempt to capture this complexity in her respondents’ “lives, aspirations, pathologies, and struggles, their visions, their coping strategies, their compromises, and modes of resistance”. And for this reason, they need to be told and re-told. But just as the tradition of story-telling goes, no re-telling of the story is the same. Their narration and reception, each time, is imbued with a different significance emanating from the personal and societal context of the narrator and the reader.

Also read: Revisiting The Questions Around Queer Women In India

For the reviewer, the use of the lenses of class and sexuality to capture the ‘life stories’ of same-sex love push us to critically reflect on how we do Queer studies in India, who is deemed as an ideal queer subject, and more fundamentally, how we understand the boundaries of queerness contextually.

Also read: Queer Politics In India: Towards Sexual Subaltern Subjects By Shraddha Chatterjee | Book Review

Akanksha Pathak is an M.Phil. student from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

Featured image source: kobo.com, Vibes of India

“capture this complexity in her respondents’ “lives, aspirations, pathologies, and struggles, their visions, their coping strategies, their compromises, and modes of resistance”. And for this reason, they need to be told and re-told. But just as the tradition of story-telling goes, no re-telling of the story is the same”

Refreshing read capturing the nuances of queer affinities so beautifully. Best Wishes! Please keep writing

Love,

A