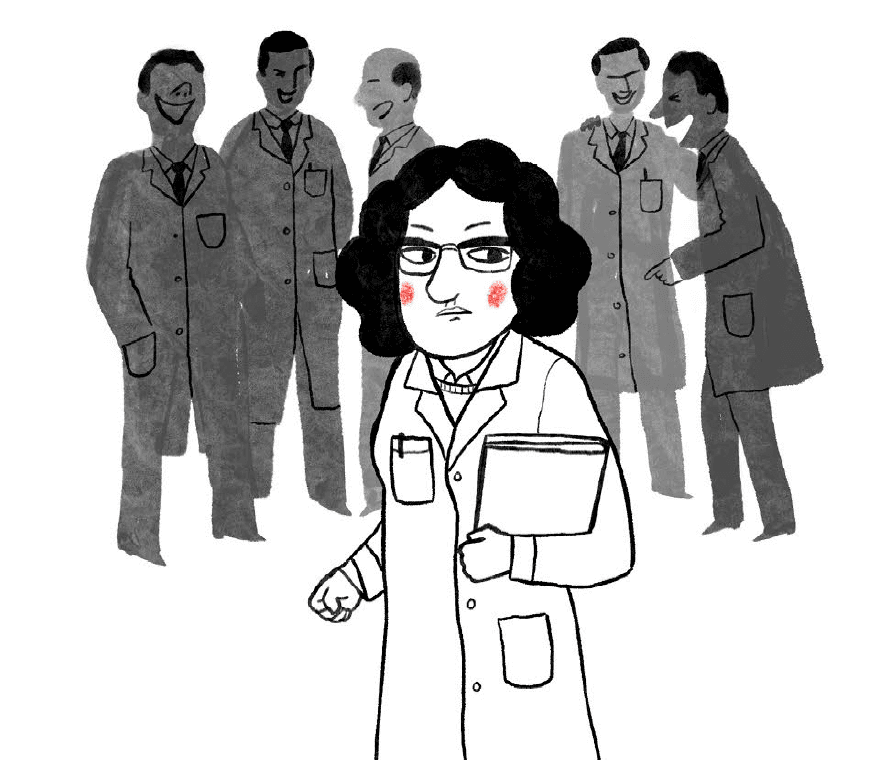

The sexual anatomy of anyone other than a cis male remains lesser understood or even misunderstood. Apart from the lack of enough research funding, this is largely also a result of the low number of female researchers exploring issues specific to their anatomy. There is a glaring dearth of female researchers attracted to, and retained in the field of women’s health.

The ones who sustain somehow in this hostile space have to fight many challenges. For some, their research topics are criticised with sexual innuendos, while for others, it is a bigger challenge to weed out the existing illusory perception about the female reproductive system than to conduct the whole research itself.

For instance, cramps have always been understood to be part and parcel of menstruation. Even doctors routinely shrugged off complaints about menstrual cramps. But such dismissal came at a cost of overlooking a condition as serious as endometriosis. The disease, in which tissues similar to the lining inside the uterus grow outside of it, is said to be found in one in ten women and also among trans and gender-diverse people. It is characterised by extreme pain and sometimes infertility.

A U.S 2020 study revealed that 75.2 percent of patients were misdiagnosed with another physical health (95.1 percent) and/or mental health problem (49.5 percent) instead of endometriosis. Even today, it is normal to take around 7-8 years to diagnose endometriosis and diagnosis does not guarantee full-proof treatment. There is still no cure for it.

Dr. Linda G. Griffith, a bioengineer, managed her severe period cramps until her graduation with 30 Advil tablets a day. It was only when she was sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as a post-doc that an accidental checkup diagnosed her with endometriosis. With no cure, she was given two options: either to use Danazol, a hormone-blocking drug, or get pregnant. She chose the former.

In 2007, after going through her eighth endometriosis surgery and helping her 30 years younger niece diagnose and deal with endometriosis, Graffiti decided to use her MacArthur genius grant for opening the Center for Gynepathology Research, the only engineering lab in the U.S that focuses on endometriosis.

In 2022, while exploring effective long-lasting, and reversible contraceptives for men beyond condoms and vasectomy, a non-hormonal contraception option was reported. It aims to avoid any side effects related to hormonal contraception including weight gain, depression and increased low-density lipoprotein (known as LDL) cholesterol levels. Ironically, these side effects have been a norm for women for decades who opt for birth control. In the face of possible pregnancy, these side effects haven’t posed a bigger risk

But she doesn’t just want to research endometriosis as a “women’s problem”. She wants to rebrand it as an “MIT issue”. Her research focuses on the uterus in its entirety, marveling at its ability to regenerate after shedding its lining every month. She is also exploring endometriosis as a gateway to understanding tissue regeneration.

A surprising fact is that bioengineers are usually looking to study tissues that regenerate. But despite the uterus being an organ with the most regenerative tissues, it never became a prime area of study. When asked the reason behind this, Kathryn Clancy, a biological anthropologist from the University of Illinois succinctly puts, “Because none of the researchers had uteruses.”

Researchers without a uterus or limited understanding of it can sometimes instead, engage in counterproductive research. For example, the study Attractiveness of women with rectovaginal endometriosis: A case-control study, was published in a reputed journal after being peer-reviewed in 2013. Its conclusion that “Women with rectovaginal endometriosis were judged to be more attractive than those in the two control groups. Moreover, they had a leaner silhouette, larger breasts, and an earlier coitarche” drew considerable criticism and was withdrawn after 7 years.

Also read: Medical Misogyny As Understood From Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wall Paper’

Dr. Kate Young, a public health researcher at the Queensland University of Technology, whose work focused on endometriosis is quoted to have said, “That paper is a really good example of what happens when we do research about women but not for them. And that’s partly a reflection of the patriarchal society that we live in and also the way we’ve structured research and research funding.”

Such disastrous conclusions, however, are not new. Notably, it was Sigmund Freud who proposed that female pleasure and orgasm should center on the reproductive tract or vagina. Along with declaring orgasms through stimulation of the clitoris as “infantile”, Freud linked the inability to have a vaginal orgasm in women with “psychosexual immaturity”.

The emphasis placed on penile-vaginal intercourse also meant an emphasis on the use of the word “vagina”. So much so that it became an overarching word meant to denote the whole female reproductive system. But its use stems from a patriarchal mindset obsessed with heterosexual intercourse that only upholds vaginal-penile penetration. Anything outside of it (or outside of the vagina) did not fit into the definition of sex and was not important enough to explore.

Even the clitoris, which is a central organ for female pleasure was understood quite late. In 1998, urologist Helen E O’Connell published the first research raising curtains on the anatomical structure of the clitoris. O’Connell was inspired to do the research owing to her experience as a medical student, which required her to study pages about anatomical drawings of penises but those that treated the clitoris like an afterthought.

Limited research means that the female reproductive system is explored only in the footnotes of the school curriculum, or even in medical textbooks. The gaps in medical research perpetuate a social stigma and vice versa. To not be caught in this vicious cycle, we must ensure that researchers in the STEM laboratories are from diverse backgrounds, gender, and sexual orientations

But this was still not a breakthrough. The mention of this groundbreaking research in the next day’s newspaper was insignificant. Even in the moment of glory, the treatment of thhe clitoris was like how it had always been: downgraded and difficult to find. A literature review conducted 20 years after the publication of the research found only 11 articles on the anatomical dissection of the clitoris.

O’Connell, who is currently working on mapping the urethra, previously also helped to fight off the myth of G-spot by anatomically dissecting the vaginal walls.

Another aspect is related to birth control and contraception. Usually, the birth control burden falls squarely on women, with easy access to pills. Most birth control pills prevalent right now employ hormonal methods. But, Bhawana Shrestha a microbiologist at UNC-Chapel Hill is currently working to develop an antibody-based, non-hormonal form of contraception, different from the existing hormonal contraception. In an interview, Shrestha recounted how her own experience led her to research the issue.

“The majority of contraceptives available in the market are hormonal contraceptives, which are associated with a plethora of real and/or perceived side effects such as acne, pelvic pain, mood disorders, etc. Many women also have medical contraindications to the use of estrogen-based hormonal contraceptives. I, unfortunately, suffered those side effects with the use of a hormonal IUD and contraceptive pills, leading me to not only discontinue their use within a short period but abstain from all hormone-based contraceptives. This personal experience was one of the main reasons behind my interest in developing a safe, non-hormonal method of contraception,” Shrestha shared.

In 2022, while exploring effective long-lasting, and reversible contraceptives for men beyond condoms and vasectomy, a non-hormonal contraception option was reported. It aims to avoid any side effects related to hormonal contraception including weight gain, depression and increased low-density lipoprotein (known as LDL) cholesterol levels.

Ironically, these side effects have been a norm for women for decades who opt for birth control. In the face of possible pregnancy, these side effects haven’t posed a bigger risk.

Of course, this is not to burden female researchers to only research their issues, but their first-hand experience gives them better access to dealing with the matter. It also means exploring new avenues to understand age-old concerns better, like the above-cited study of the uterus to understand tissue regeneration better.

Limited research means that the female reproductive system is explored only in the footnotes of the school curriculum, or even in medical textbooks. The gaps in medical research perpetuate social stigma and vice versa. To not be caught in this vicious cycle, we must ensure that researchers in the STEM laboratories are from diverse backgrounds, gender, and sexual orientations. To reiterate O’Connell, “There are so many things young people can do to create good science, you create a better future.”

Also read: Technology And Reproductive Choices: Is Egg Freezing As Feminist As We Believe It To Be?

About the author(s)

Shuvangi is an independent writer and researcher based in Kathmandu, Nepal