Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for July 2022 is Gender and Environment. We invite submissions on the many layers of this theme throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly refer to our submission guidelines and email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

In a single Google search, one can find various lists naming young environmental activists from all around the world. Climate strikes started by then 15 year old Greta Thunberg have snowballed to different countries, inspiring young people to take climate action. These young minds are now not only attending international conferences, but also protesting against such orchestrated drama with no visible effect.

A landmark survey done amongst 10,000 young people in 10 countries found that most respondents were concerned about climate change. Nearly 60 percent said they felt ‘very worried’ or ‘extremely worried’. This fear is usually interlinked with the feelings of betrayal and abandonment by governments and adults.

In a country like Nepal, environmental protests are a relatively new phenomenon. In 2003, research was done on social movements in Nepal among 800 activists from Pokhara, Janakpur, and Kathmandu about their goals and motivation. Out of 14 categories of protests, environment or climate simply wasn’t a reason for social activism at that point.

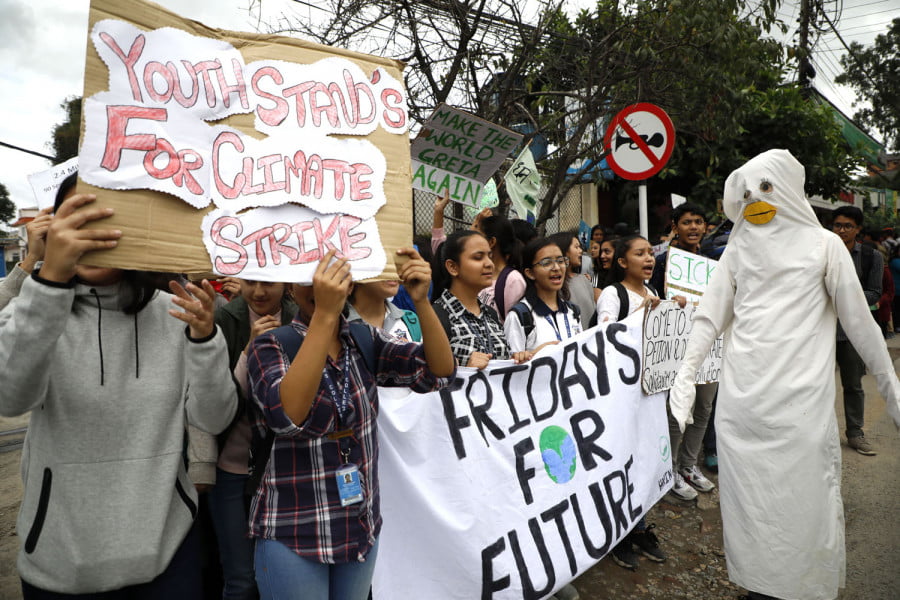

But things have changed in the last few years. Marches and rallies are increasingly being held demanding climate justice. In 2019, inspired by the international movement Fridays for Future, Nepali youths hit the streets, contributing to the climate movement. Many of such protests were organised by a young organization, Harin Nepal, founded in 2018.

Harin Nepal came into existence when one of its co-founders, Tanuja Pandey, 21 year old hailing from Terai region found out about the Nepal government’s plan to clear out a forest area of 2.4 million trees in Nijgadh of Terai. This was to build a second international airport in Nepal. If built, this would be the largest airport in South Asia in terms of area. But it came at a huge cost.

“People advocating against it at that time were mostly from elite groups. They were concerned about the animals and trees. But for the Terai, it is important for basic food and water. We didn’t want to focus just on environmental impacts but also on social and economic impacts, especially on gender. This was a threat multiplier for women and especially Madhesi women so we wanted this issue to be addressed in a multi-disciplinary approach.” Tanuja recalls.

A writ against the government’s plan had already been filed in the highest court of Nepal. But the group worked on the streets to exert public pressure on the judiciary. “We would send letters to different schools and ask them to send their students to participate in demonstrations” Subigya Poudel, 21, co-founder of Harin Nepal talks about the past days. “In the beginning only the group members of 3-4 would be present. But slowly the number increased to hundreds.” she says.

Also read: The Attribution Of ‘Backwardness’ To Indigenous Communities And Environmentalism

It is never easy to mobilise and build movements. But another loose network of youths have been doing it relentlessly for almost 14 years now. Laxmi Sapkota, 23, who is a current core team member of Nepalese Youth for Climate Action (NYCA) speaks with pride about how they have been managing with zero budget for years, whether facilitating workshops or holding discussions.

After 14 years, do the members still fall in the “youth” category? Laxmi smiles and assures, “The age group of people involved is 18-29. Mostly we in the core team work for a few years and then hand over our responsibilities to younger generations.” She says it can also be understood as a female led network as the majority of women in the core team are females.

The work is not without danger or apprehension. Along with people undermining female leadership and voices, protests are never a favorable site for marginalised populations. “Usually there are no female police so police can just grab you anywhere if (when) you get arrested.” Tanuja shares. Activism can also be tiring and demanding. But sometimes a glimmer of hope appears when the people with power actually take notice

Laxmi came to Kathmandu from Dhangadhi for her higher studies. She was shocked at the first sight of the city. Coming from a region where she had basically lived in the laps of forests, to see a city bare of any greenery. Laxmi who had come here to study MBBS changed her subject to forestry. Then she was introduced to NYCA.

NYCA has 17 regional chapters working throughout Nepal. This allows local activists to take up issues specific to their region. For e.g., currently NYCA Baitadi chapter is running climate smart farms in agriculture. Harin Nepal, which targets today’s youth focuses on digital awareness, but at the same time, understands the importance of working at the ground level. Tanuja and her friends like to call themselves grassroot activists. Even though advocating against the Nijgadh airport garnered them considerable public exposure, Harin Nepal works at the ground level going into communities of Tharu, Dhimal and other indigenous groups mainly located in Terai.

“Sometimes I think my work is nothing compared to activists who have worked and sacrificed so much,” her friends agree with Tanuja. She speaks about Omprakash (Dilip) Mahato, an activist who was killed for speaking against illegal excavation of sand and stone. “His sisters are still raising their voice against it. But such people rarely get space,” she says.

They also claim almost all the activists they have met in the grassroot level are women. “But after all the work has been done and when it’s time to take credit, somehow a man appears,” Subigya says. Working with communities facing real impact comes with a set of challenges. They range from issues of literacy, level of understanding to use of language and culture. Over a phone call with Azeena Adhikari, 22, network co-ordinator of NYCA Baitadi regional chapter, she talks about challenges working with the local community there.

“Most of them are dependent on forests. So, we cannot tell them not to cut down trees directly just because it will impact the environment. Because their main source is forest. It is easy to talk about those alternatives in Kathmandu. But while working here, we need to provide alternatives for them that are affordable. Along with climate change we have to think about their survival and livelihood management. It is difficult for them to buy gas instead of using wood. So it is a little difficult to work here“, she says.

NYCA aspires to be ambitious in its approach to include people from diverse backgrounds. But Laxmi admits they haven’t been fully able to include people with disabilities or those from LGBTQIA+ community. “We are trying to explore and find more about specific issues they face due to climate change”, she says.

Bipana Adhikari, 22, another co-founder of Harin Nepal who belongs to the LGBTQIA+ community echoes the sentiment. For her, it is important what people perceived of the Pride walk organised just last week. “People think it’s only about freedom of the LGBTQIA+ community. But during my conversation with them, I realised that even they want to engage in work related to climate change. They feel that they are mostly outcasted.”

Shilshila Acharya, director of Avni Center for Sustainability (ACS) who started out as an activist around 10 years ago, still feels that the climate movement in Nepal has not been as inclusive as the diversity the country boasts. “In the city, people think of climate change as a lucrative, money making thing. While it is still difficult to engage youths from rural areas, who have the actual field experience. It is especially difficult because people who are working there may not be even using the word “climate change” but they are the ones most affected and vulnerable due to climate change”, she shares.

The presence and experiences of these activists and advocates show that there are more women on the ground when it comes to environmental activism, whether it be the ones who take the brunt of climate change or the ones who advocate for it. What is now necessary is for effects to trickle down to the ground level to achieve the objectives of environmental justice

Initially she started her advocacy by calling out for reduced use of plastics. “After a few years of protest, the government did bring a policy to prohibit single use plastic in Kathmandu valley but somehow implementation fizzled out. Now after 10 years, this issue has come to their priority list.” The World Bank is funding to implement the policy of banning single use plastic throughout Nepal. “Now they are thinking about single-use plastic when we have bigger problems related to garbage and e-waste,” Shilshila says.

Something that inspired Shilshila to venture out was reflecting on the role of activist once advocacy issues made it to the policy level. “After it has become a policy, it is upto government to ensure its implementation. But I figured through business type solutions we can keep the momentum going.” For the past 3 years Shilshila has been working in waste management, segregating and recycling the waste through her company, Avni ventures.

Shilshila reflects over her decade long experience in advocacy. “Years ago, in plastic banning demonstrations among 3000-4000 youths, there would be 70-80% of females. In our classes where we teach about sustainability, more than 60% are females in every batch. When we called for fellows to record indigenous knowledge within their communities, even then the number of applications from females was quite high.” She further shares that in her experience many women are retained in the field for longer as compared to men. “Look at myself, I have been here for more than 10 years now,” she says with a smile.

She attributes this to empathetic and sensible leadership qualities among females. “The long-term values that we need, like thinking for others, working together, and being empathetic about others are traits that mostly females possess. I feel that women in leadership positions usually don’t make rash or power hungry decisions as they think about children and families,” Shilshila says.

Also read: Sugathakumari: Poet And Environmental Conservationist Who Fought To Save Kerala’s Silent Valley

dfadf.jpg)

The work is not without danger or apprehension. Along with people undermining female leadership and voices, protests are never a favorable site for marginalised populations. “Usually there are no female police so police can just grab you anywhere if (when) you get arrested.” Tanuja shares. Activism can also be tiring and demanding. But sometimes a glimmer of hope appears when the people with power actually take notice.

After a huge public debate spanning 5 years, regarding the construction of the Nijgadh airport, in May 2022, the Supreme Court of Nepal made a landmark judgment directing the Nepal government to quash all decisions regarding the construction of the Nijgadh airport. The young minds from Harin Nepal however, are still not convinced. “You never know until you get the full judgment,” Tanuja says. Recently they also handed their 6-point road map to the Ministry of Environment, which calls for relocation of indgenous group of Tangiya Basti and reforestation among other things.

The presence and experiences of these activists and advocates show that there are more women on the ground when it comes to environmental activism, whether it be the ones who take the brunt of climate change or the ones who advocate for it. What is now necessary is for effects to trickle down to the ground level to achieve the objectives of environmental justice.

Featured Image Source: The Kathmandu Post

About the author(s)

Shuvangi is an independent writer and researcher based in Kathmandu, Nepal