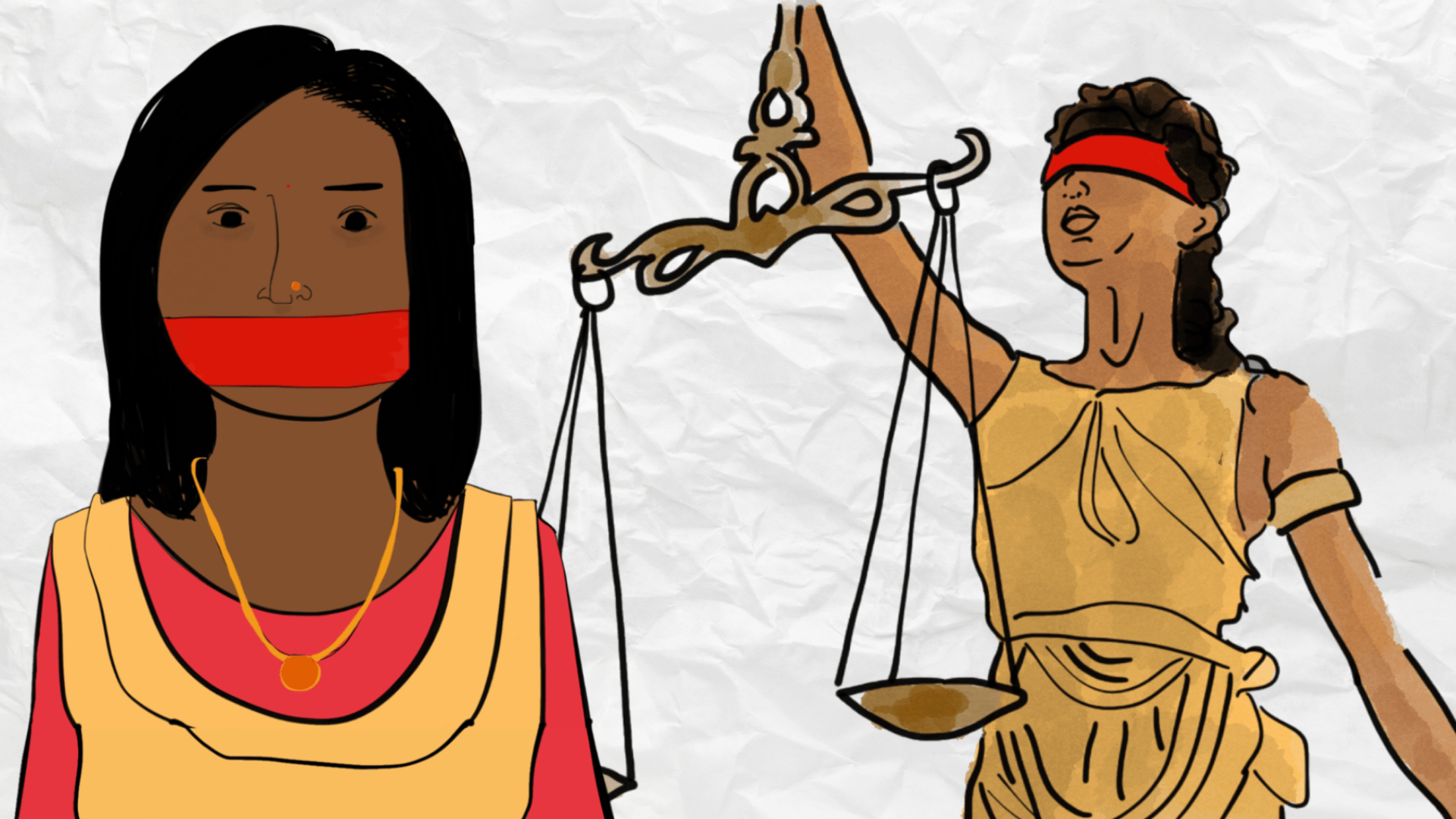

The Indian constitution guarantees in Article 14 the right to equality and non-discrimination. However, the legal landscape is far from effectuating this constitutional promise. Particularly, the present constitutional and legal framework does not address intersectional and horizontal discrimination because discrimination law statutes are scattered and cumbersome.

Unaddressed Intersectional Discrimination

Multiple marginalising identities can intensify disadvantages for those who belong to more than one disadvantaged group, understood as intersectional discrimination. Article 15 of the Indian constitution does not account for intersectional discrimination. It prohibits discrimination only on the grounds of race, religion, class, sex and place of birth.

In the case of Anjali Roy v State of West Bengal where the policy of a college to not grant admission to women was challenged. The court held as follows,

“….the discrimination which is forbidden [in Article 15(1)] is only such discrimination as is based solely on the ground that a person belongs to a particular race or caste or professes a particular religion or was born at a particular place or is of a particular sex and on no other ground. Discrimination based on one or more of these grounds and also on other grounds is not hit by the Article.“

This reasoning was further cemented in the case of AIR India v. Nargesh Mirza where the constitutional validity of Air India Employees Service Regulations was challenged. The court stated,

“What Articles 15(1) and 16(2) prohibit is that discrimination should not be made only and only on the ground of sex. These Articles of the Constitution do not prohibit the State from making discrimination on the ground of sex coupled with other considerations.”

Also Read: Abortion Decision: Why Does Legislation Override The Choice Of Women?

Legislations like the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016, The Schedule Castes and Schedule Tribes Prevention of Atrocities Act, 1989, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 protect different characteristics and operate in silos, thereby eliminating the possibility of raising a claim of intersectional discrimination. Multiple sections are applied for jurisprudence, but it makes the law difficult to comprehend and inaccessible.

For instance, section 3 (2) (v) of the SCST act states that “whoever commits any offence under the Indian Penal Code is punishable with imprisonment for a term of ten years or more against a person or property on the ground that such person is a member of a Scheduled Caste or a Scheduled Tribe, shall be punished with imprisonment for life or fine.“

The courts have often interpreted “on the grounds of”, which means only on the grounds of caste. Such interpretations have ruled out the possibility of any intersectional analysis.

Unaddressed Horizontal Discrimination

Most of the fundamental rights in the Indian Constitution including Article 15 are enforceable against the state and not against private entities. The only exceptions are Article 15 (2) and Article 17 which are also enforceable against private entities.

However, the scope of these two articles is limited. Article 15 (2) states,

“No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and palaces of public entertainment.”

In Zoroastrian Cooperative Housing Society vs District Registrar Co-operative Societies (Urban) and Others, the Supreme Court endorsed one such restrictive bond, and it upheld a bye-law of a Parsi housing society that prohibited the sale of the property to non-Parsis. The court held that this bar on sale was intrinsic to the Parsi communities’ right to associate with one another. The court further held that the transaction was contractual in nature and was not hit by Article 15, as the parties had the freedom to contract.

Scattered statutes do not do much to counteract horizontal discrimination. SC/ST act is enforceable against private individuals, but it only talks of caste and not any other protective marker. RPWD act provides that private entities should notify equal opportunity policies. But these obligations are not mandatory. Similarly, the POSH act has a number of implementational challenges due to the power dynamic between the employer and the employee.

These legislations at best, provide for a half-baked mechanism for imposing penalties on the entity that discriminates against the specific markers covered under them. Still, none of these legislations talk about a positive duty to ensure equality and diversity.

Legal Jurisprudence

Having a full-fledged Equality Act can be useful in addressing these two major pitfalls for jurisprudence in India. It is important to recognise the complexities of discrimination. Two bills have been drafted by Professor Tarunabh Khaitan and Center for Legal Policy. The former had been tabled before the parliament by MP Shashi Tharoor but it lapsed.

Neither of the bills in entirety can claim the end of discrimination, but they call for a better response from the State. These drafts had many more protective grounds beside the ones mentioned in the constitution. They provide more concrete mechanisms for enforcement, compensation and penalties and also cover intersectional, horizontal and indirect discrimination. Thus, an alternate policy is available and accessible but popular support and political support remain amiss.

About the author(s)

Anchal is a second year student at national Law school of India University, Bangalore.