Trigger Warning: Mention of Rape and Gender-Based Violence

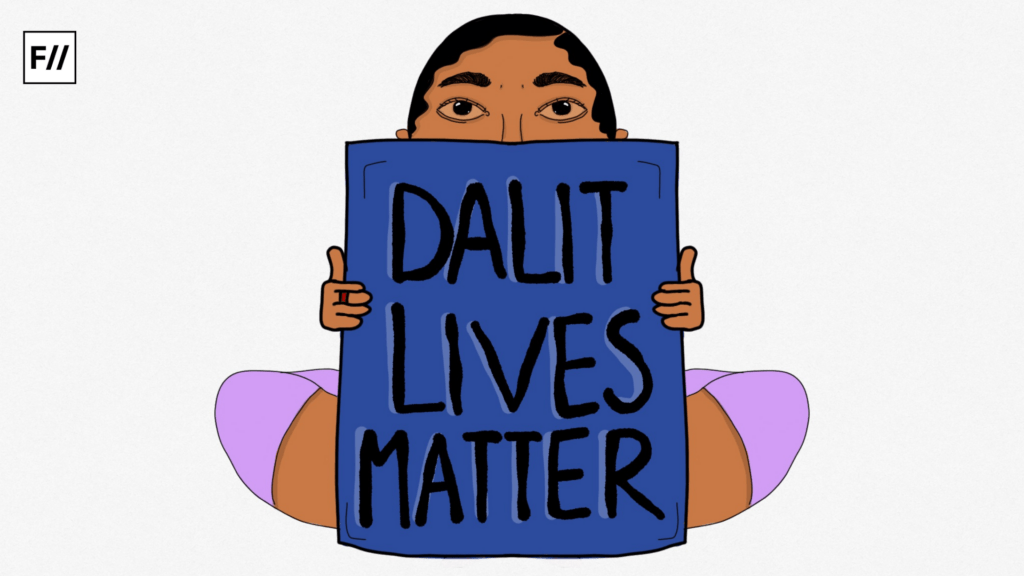

On 2 March 2023, in absolute shock to the nation, the UP court acquitted three of the four accused in the rape and murder of a 20-year-old Dalit woman in the Hathras district. It charged the main accused only for culpable homicide, the verdict revealing that he did not have the intention to kill. None of the upper caste men has been charged with rape as the traumatised victim had not mentioned the word rape or sexual assault in her last statements. The victim’s body was cremated by the police without the family present and was later claimed that she was not raped at all. The honourable justice system asked everything out of the dying victim – clarity in statements, clear identification of victims and the onus of proving that she was violated and yet asked nothing out of the police or the administrative systems surrounding it.

The construction of sexual violence divorced from the identities of the victims has become the norm to facilitate the indifference of the public and the cruelty of the power structures to victims from marginalised communities – tribals, Dalits, Muslims etc.

This verdict comes from a country that witnessed massive protest movements following the ‘Nirbhaya case‘. But this also comes from the country that celebrated the premature release of 11 men accused in the gang rape of Bilkis Bano in Gujarat. The survivor has to now forever live in the shadow of fear as the justice system of this country has proven that it is not supportive of her struggles. Even the Mathura rape case, which was a watershed moment for legal reforms in cases of sexual violence against women, saw the survivor – a tribal girl, 16 years at the time, being denied justice. The reasons were questions regarding her chastity and the fact that her non-consent was non-verbal.

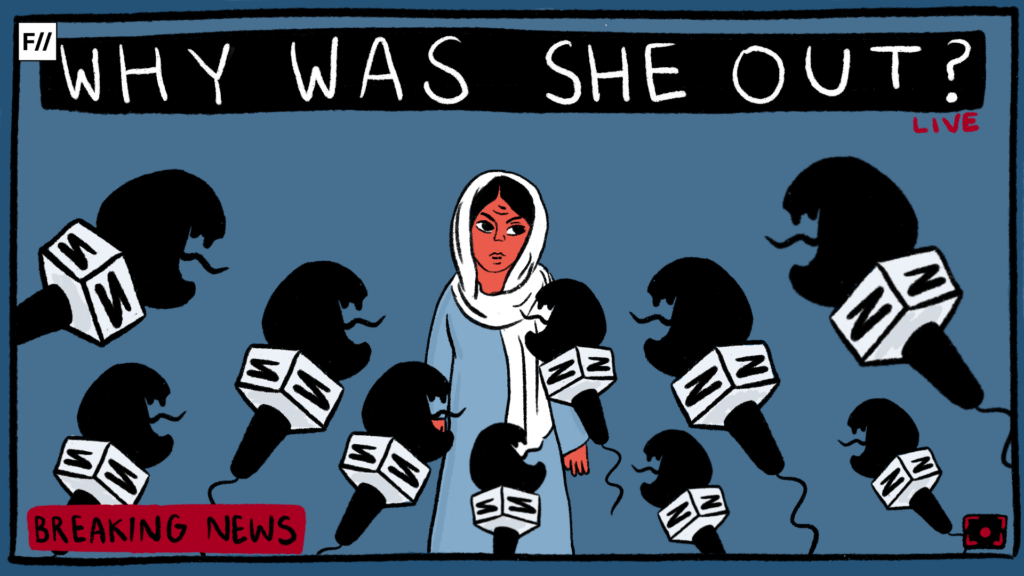

What was different about these cases? While the Nirbhaya case was reported as a blotch on India, the Hathras case was initially reported as a love affair gone wrong. The family of the victim from Hathras gives us the answer. Talking to India Today, they say that “they got the justice a Dalit deserves” and that “the verdict was according to their caste”. As the Caravan has reported, scholar Jayshree P. Mangubhai asserts in a chapter for the second volume of Fault Lines of History: The India Papers that the Nirbhaya case’s lone emphasis on gender “displaced attention from the differences among women in the country, flattening them into a single caste-less, religion-less, and class-less identity.” This construction of sexual violence divorced from the identities of the victims has become the norm to facilitate the indifference of the public and the cruelty of the power structures to victims from marginalised communities – tribals, Dalits, Muslims etc.

Also Read: One Year Since The Gangrape Of A Dalit Girl In Hathras

Estelle B Freedman in her analysis of sexual violence in American newspapers from 1870-1900, notes victimology as an important feature in studying the intersections of racial identity and gender, among other indicators. She notes that the most credible victim for the jury was the innocent white woman who fought off her attackers. She also talks about the unequal justice system under slavery, which did not consider the rape of black women by their masters as a crime. Freedman has also found that even for emancipated black women, biases regarding their chastity have made judgements in their favour, rare.

A quick look into the Hathras case as well as the case of Bilkis Bano is enough to show the similarities between the black victims in the US that Freedman studied and victims from marginalised communities in India. While pronouncing the judgment on the Hathras case, the court proclaimed that “a girl or a woman in the tradition-bound, non-permissive society of India would be extremely reluctant even to admit that any incident which is likely to reflect on her chastity had ever occurred.” The emphasis on chastity in the event of sexual assault is not only extremely regressive but also revealing of the court’s biases.

Flavia Agnes’ analysis of the two different victims of the Shakti Mills case, however, forces even the most identity-blind person to do a double take. The first victim, from an educated upper-class background, is given VVIP treatment and the state paid for her medical expenses. The second victim, from a scheduled caste background on the other hand, was forced to undertake the two-finger test and was made to travel to the police station multiple times. The second victim almost faded into the background, despite being assaulted a month prior and with the same brutality.

Not only are the marginalised groups more vulnerable to this kind of violence but even their access to a fair judgment is hindered by systems that trivialise their trauma. It would be a disservice to the multitude of discrimination that such communities face to suggest that it is only in courts that they have to face this apathy.The ignorance of the trauma of these marginalised communities is built into everyday systems like the police or medical centres that they have to visit following the harrowing ordeal. In addition, there are strong cultural markers of morality and honour. For instance, the upper-caste culture of the accused was cited in the Hathras case as a testament to their character and behaviour – that a man would not rape a woman if his relatives are around. Just like the racially discriminatory systems in America perpetuated the systematic blindness towards black victims, caste and communal systems operate as barriers for women from marginalized communities to even hope for justice, let alone dignity.

Also Read: ‘What Was She Wearing?’: Rape Culture And The Thriving Narrative Of Victim Shaming

It might sound easy to designate these cases as a few outliers of an otherwise perfect system. As in the case of many other things, for the privileged masses, it is easy to adopt the ‘identity-blind lenses’, even in crimes against women. After all, it was that straight-jacket formula that the Nirbhaya case offered to India. Flavia Agnes’ analysis of the two different victims of the Shakti Mills case, however, forces even the most identity-blind person to do a double take. The first victim, from an educated upper-class background, is given VVIP treatment and the state paid for her medical expenses. The second victim, from a scheduled caste background on the other hand, was forced to undertake the two-finger test and was made to travel to the police station multiple times. The second victim almost faded into the background, despite being assaulted a month prior and with the same brutality.

The criminal justice system in India fails to provide the victim of the crime and those close to them with any type of structural, financial, legal, or psychosocial support, further traumatising them and making their trauma invisible. Also, civil society interventions have a history of being disproportionately perpetrator-focused.

In today’s political climate where echoes of ‘bring back Manusmriti’ – the code of law that preserves caste inequality and ‘kill the Muslims’ gain more traction, violence against marginalised identities is slowly meeting banal normality. Indifference is not what Bilikis Bano or the Hathras victim or the countless women that cannot be named deserve; they deserve rage – rage not only against toxic masculinity that violated them but against systems of caste, class and religion that continue to violate their soul even after the violence is done.

The disproportionate persecution of people from marginalised groups by the justice system is challenged by some significant interventions, but they frequently fall short of addressing the many challenges survivors face, including the suffering brought on by isolation, the political and social pressures placed on family members to drop charges, and the lack of proper police protection.

Also Read: Victim Blaming, Love Jihad And Islamophobia: Is There A Room For Justice For Women In India?

Reading Anand Teltumbde’s work on caste atrocities becomes significant in this context. Whether it is the Khairlanji massacre or the Hathras case, Teltumbde shows us that the savagery, the destruction of evidence, or the outrageous, despicable press manoeuvres are not novel.

In today’s political climate where echoes of ‘bring back Manusmriti’ – the code of law that preserves caste inequality and ‘kill the Muslims’ gain more traction, violence against marginalised identities is slowly meeting banal normality. Indifference is not what Bilikis Bano or the Hathras victim or the countless women that cannot be named deserve; they deserve rage – rage not only against toxic masculinity that violated them but against systems of caste, class and religion that continue to violate their soul even after the violence is done.

About the author(s)

Stephy is a masters student in Jamia. Her interests revolve around issues of conflict and peace, gender and mental health. She hopes to shed her inherent biases daily and become a better ally each day