Rituparno Ghosh’s untimely and sudden demise in 2013 took away a safe space, that one could fall back to through watching his films. Most of his viewers often speak of deep connection and comfort in watching his work. His films are mostly enriched with a certain sense of lyricism and poignant style of conversation, that delves into complex human relationships.

What makes Ghosh’s movies a beautiful revelation is his “true understanding of the female psyche” and his own queer-feminist position that is effortlessly spilt over in his storytelling.

From earliest works such as Hirar Angti (1992) to Chitrangada (2012) which marked the untimely end of the genius’s craft, issues of gender have been a central theme in his narrative style.

Source: Telegraph India

What makes Ghosh’s movies a beautiful revelation is his “true understanding of the female psyche” and his own queer-feminist position that is effortlessly spilt over in his storytelling. Sangeeta Datta and Rohit K Dasgupta argue that “In film after film, Ghosh attributes to his female protagonists an agency or reflects on the lack of it and makes them question their subordinate status. He vociferously challenges the accepted dynamics of power equations between men and women, parents and children, and straight and queer people.”

Passionate mothers and questioning daughters

Ghosh’s films dealt with issues of sexuality, oppression, desire, pain, and melancholy. The women protagonists in each of his films invited us into their middle-class urban lives, filled with challenges and longings, and their constant negotiations with the domestic. However, this piece does not intend to be a commentary on Ghosh’s filmography but instead looks back at a particular theme of mother-daughter relationships that is explored in two of his films Unishe April (1995) and Titli (2002), which perhaps urged me to think beyond the whitewashed imaginations of the mothers and daughters as entities.

Namely, the mother as a figure of selfless love and sacrifice, upholding the morals of society and ideal daughters as those who remain obedient and unquestioning. In Unishe April, a film set in a South Kolkata house on a gloomy day captures the emotional turmoil and dilemma between the mother, Sarojini (an awarded classical dancer) and her daughter, Aditi (a recent medical graduate).

Source: Indigenous Web

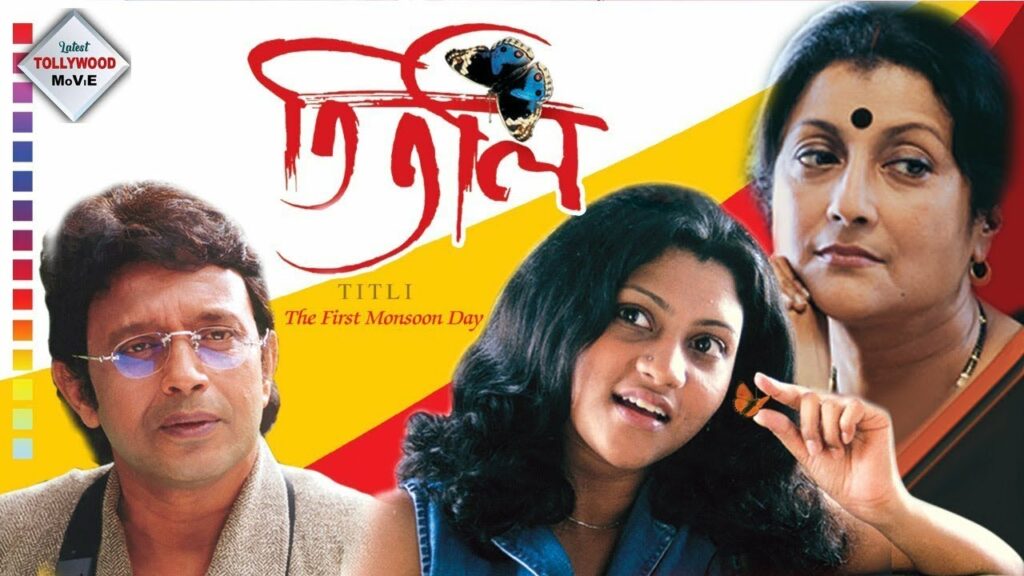

Titli on the other end is set in foggy Darjeeling and typically narrates the tensions between Urmila (a homemaker) and her 17-year-old daughter Titli, taking a car journey through the hilly roads to pick up the father from the airport, when they meet a popular movie star, who happens to have a past with Urmila. In both films, the mothers are played by Aparna Sen, and she essays the reticent spirit quite flawlessly.

While Sarojini and Urmila represent two ends of the spectrum, one as a professional dancer and the other as a successful homemaker, they are both unique in maintaining their passions. Sarojini derives her happiness from her work and wouldn’t compromise it and Urmila is tirelessly maintaining her home as we see in the beginning of the movie and finds her joy in knitting and cooking.

While Sarojini and Urmila represent two ends of the spectrum, one as a professional dancer and the other as a successful homemaker, they are both unique in maintaining their passions. Sarojini derives her happiness from her work and wouldn’t compromise it and Urmila is tirelessly maintaining her home as we see in the beginning of the movie and finds her joy in knitting and cooking.

Although far removed from one another’s world, both Sarojini and Urmila have more in common than different, they don’t smother their girls and they certainly don’t shy away from their pasts and passions, finally, they are unapologetic for their choices. In one scene in Unishe April, Aditi who is estranged from her mother bitterly complains to her during an outburst, that as a child her mother neglected her to keep up with her own work and never even baked a birthday cake for her.

Source: Hoichoi TV

A disturbed Sarojini retorts after a while, “Would you have preferred your mother be an economist or a professor, rather than a dancer?” Of the many brilliant moments in the film, Sarojini’s response particularly strikes out as an uncanny reminder of the question of respectability and certain jobs, in which artists are cordoned off as precarious. It perhaps even goes on reveal Sarojini’s own insecurities about pursuing a career.

Source: Youtube

However, the brilliance of Ghosh stems from the fact that Aditi the daughter steps in even amidst the bitter argument to console her mother that her identity as a dancer was never the issue but rather her lack of time as a parent. Similarly, in Titli, towards the end, when Urmila receives a letter from her old friend and lover, Rana (now a movie star and also her teenage daughter’s crush), she sits quietly by the window, perhaps experiencing an inexplicable sadness, her teenage daughter sits down beside her and asks her “ma tomar koshto hocche?” (Do you feel sad?) and the two share a quiet moment of comfort and friendship, which seems like their own personal moment of secrecy and bonding, hidden from the rest of the world.

Forging friendships through healing

Both Sarojini and Urmila are not picture perfect for their daughters, while in Unishe April, the turmoil between the mother and the daughter stems from the daughter’s unprocessed grief of losing her father as a child and the subsequent vilification of her mother. Titli is much younger and adores Urmila until she learns during the car ride that her movie star crush (Rana) is her mother’s college sweetheart.

Titli feels betrayed and blames her mother for not sharing her past. She bursts out crying in a confrontation and Urmila first scolds her and then consoles her that such feelings of rivalry she is experiencing towards her mother are quite baseless and childish. Both Titli and Aditi at some point even portray a certain sense of muted jealousy towards their mothers, for they are everything that the daughters are not, desirable, passionate, and stronger women.

Titli feels betrayed and blames her mother for not sharing her past. She bursts out crying in a confrontation and Urmila first scolds her and then consoles her that such feelings of rivalry she is experiencing towards her mother are quite baseless and childish. Both Titli and Aditi at some point even portray a certain sense of muted jealousy towards their mothers, for they are everything that the daughters are not, desirable, passionate, and stronger women.

Source: The Citizen

Such layering of emotions is what humanises these relationships and takes them away from other stereotypical portrayals. Emotions such as grief, jealousy, and abandonment that purport vilification in these stories urge us to think of our own limitations of imaging parents as flawless entities and perhaps that is when Ghosh’s storytelling drives us to question and introspect.

Even though their journeys start from a point of conflict, where the indoors of the house in Unishe April and the cramped-up space of the car in Titli, serve the purpose of enhancing tensions between the mother and daughter, ultimately the individual stories take us to a climactic point of resolve and appeasement.

Even though their journeys start from a point of conflict, where the indoors of the house in Unishe April and the cramped-up space of the car in Titli, serve the purpose of enhancing tensions between the mother and daughter, ultimately the individual stories take us to a climactic point of resolve and appeasement. The characters have had their outbursts and expressed their resentments and healed each other in the process. As a viewer, I felt the healing was achieved through both Sarojini and Urmila speaking about their romantic pasts and choices to their respective daughters.

Sarojini admits that even though she had fallen in love with her deceased husband (Aditi’s father), she rarely felt appreciated or understood in the marriage, which ultimately led to the couple’s estrangement. She explains to her daughter that perhaps she was not meant for a marriage, she felt as if her artistic sensibilities were not designed to be domesticated. Aditi in understanding her mother learns to forgive her and, in the process, heal her own feeling of abandonment.

Source: NCPA

Similarly, Urmila in one of the final scenes explains to Titli, how it was essential for her to move on from her previous relationship with Rana and marry her husband (Titli’s father), as she desired a well-settled domestic life, that Rana as a struggling actor could never provide back in the day. Titli learns to respect her mother’s choice, as well as through this revelation soothes her own teenage heartbreak (having had a crush on the movie star previously).

Like most of other Ghosh’s films both Unishe April and Titli are primarily invested in exploring tumultuous interpersonal relationships and complex human emotions, but what sets them apart for me is the very fact that they choose to explore the much-overlooked bond of a parent and child, more significantly a mother and daughter. In common sensical understanding, parent and child relationships follow a strict black-and-white narrative, either filled with an abundance of love or estrangement.

Both stories take us through this journey of turmoil and resentment to an ultimate friendship that the mothers and daughters have achieved. Their flawed relationships emerge as a stronger bond of being understood and forgiven, allowing the viewer a sense of hope for these characters.

Source: The Indian Express

Like most of Rituparno Ghosh’s films both Unishe April and Titli are primarily invested in exploring tumultuous interpersonal relationships and complex human emotions, but what sets them apart for me is the fact that they choose to explore the much-overlooked bond of a parent and child, more significantly a mother and daughter. In common sensical understanding, parent and child relationships follow a strict black-and-white narrative, either filled with an abundance of love or estrangement.

Ghosh offers us a nuanced storyline, where the characters struggle with a multitude of emotions, often pent up and misunderstood. In doing so, the stories offer us many new lenses to see motherhood, namely, mothers with pasts and mothers with desires. The daughters on the other hand are fearless and rebellious in addressing their difficult emotions, even if it leads to confrontations. Thus, breaking societal notions of “obedient and good” children are those who rarely challenge their parents.