The representation of caste identities, biases, and storylines that reflect the predominant socioeconomic system has a long history in Indian cinema. Characters from lowered castes are typically depicted as victims and subhumans. Whereas gender norms and stereotypes have been constructed and reinforced in large part because of the cinema.

Traditional gender norms, objectification, and a lack of agency are frequently traits of women’s roles in Indian cinema. Hence the caste and gender interaction further complicates the representation in cinema. The representation of the bar dancer/item girls is an illustration of this complexity.

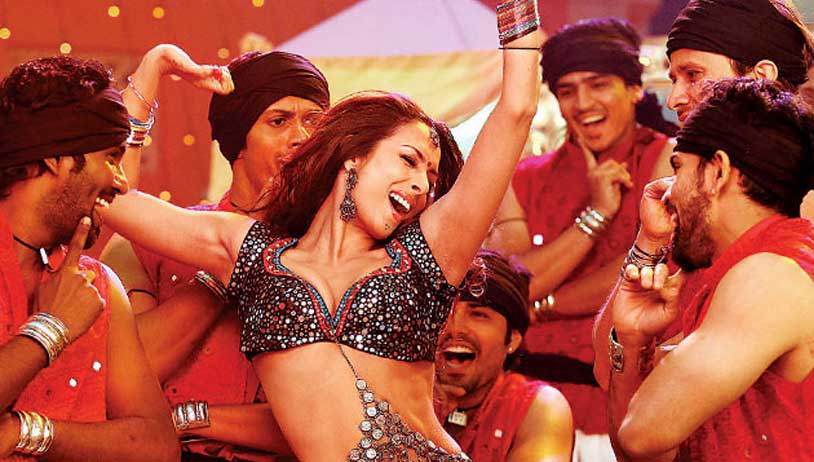

It is customary in Indian cinema to have item songs performed by female actors. The term “item” itself demonstrates that the “object” is being displayed on the screen. The item songs that are frequently put into films between scenes or at the end of the film don’t make any sense in terms of the main narrative, these item songs are designed purely for the male gaze.

Item song dancer is extremely objectified through the layered lyrics and seductive dance moves to placate men or groups of men, and even the projection of the camera is exceedingly sexualised. The question is, who are these women, where are they from, and where are they in society? Many academics have suggested that in real-time Bar dancers and prostitutes come from certain castes and have been forced to do sexual labour based on caste.

These interlocking power relations can be reflected in and challenged by cinema. It can act as a forum for discussing caste-based violence and discrimination, highlighting the experiences of Dalit women, and adding to a larger social conversation on caste and gender equality. But the issue is, to what extent does Indian cinema succeed in highlighting the way that caste and gender interact to generate various forms of dominance, or does cinema just reinforce these stereotypes and preconceptions?

Who are these bar dancers?

The societal background of these women, who act as bar and tamasha dancers in real life, was not well portrayed in Indian films. The circumstance that forced the reel bar dancer to enter this profession induced by her socioeconomic status is depicted in Indian cinema in a way that inherits the Brahminical patriarchy.

Only the contingency’s plot will be significant to be aired if the star actress in the film plays the part. For instance, the role of bar dancer “Mohini Joshi,” played by Deepika Padukone in the film Happy New Year falls in love with a male lead actor named Charli, who asked her to be the dance teacher and ends up leading a happy ending. Raveena Tandon’s role as “Jaya, the Bar Dancer” in Ziddi and Karishma Kapoor’s bar dancer character in the film Khuddar both decided to become bar dancers to support their families and orphaned children, respectively.

This demonstrates that these women are morally upright and uphold their obligations as good daughters and women who sacrifice their dignity for the well-being of others. However, once the hero has fixed all of her difficulties with his patronising behaviour, she is ready to become a decent wife.

Gender and class are shown in Indian films as the reasons for their miserable situation. While the dancers who don’t play the lead actress aren’t necessary for their backstory to be shown, they are frequently portrayed as vamps and gold-diggers.

Caste and the bar dancers

Indian film has a long history of presenting caste identities, prejudices, and stories that represent the dominant socioeconomic structure. This includes portrayals of people from higher castes as heroes or heroines, whilst characters from lowered castes are frequently put in clichéd or marginalised positions. The way that caste influences a bar dancer’s status is completely overlooked in this image of bar dancers which is caste oblivious.

As Paik argues that ‘Tamasha‘ is practised predominantly by Dalits for a long time and The Dalit Tamasha women played a central role in these performances, representing both the desire and disgust of a patriarchal society. According to upper castes’ norms and values, Dalit women were already in the public gaze and did not need to concern themselves with issues of dignity and honour.

Meena Gopal demonstrates the problematic relationship between caste, sexuality, and labour in her paper “Caste, Sexuality, and Labor.” According to her, women who participate in Tamasha, bar dancing, prostitution, and nautanki for men’s amusement are members of particular caste communities like the Kohlati and Bedia communities. Women from the marginalised castes of the Bedia, Kohlati, Nat, and Dedar from north India were employed as bar dancers, tamasha, and nautanki and Lavani performers for the family livelihood.

As Paik argues that ‘Tamasha‘ is practised predominantly by Dalits for a long time and The Dalit Tamasha women played a central role in these performances, representing both the desire and disgust of a patriarchal society. According to upper castes’ norms and values, Dalit women were already in the public gaze and did not need to concern themselves with issues of dignity and honour.

Dalit women carry the stigma of being untouchable and pose a challenge to the established order since their bodies are ‘polluted‘ and are not intended to be touched openly in public as doing so would taint society. Ironically, the same body turns into a consumable body that can be controlled and imprisoned by the same hierarchical society that usually criticises the bodies. Thus, Dalit corpses are shown on the screen as examples of abstract labour.

Paradoxically, while their “femininity” made them sexually vulnerable to racist and casteist domination, their Blackness and Dailtness effectively denied them any protection (Paik, 2014.) The women of the higher caste, in contrast, usually appeared dignified and respected and were instructed to keep their sexuality tidy and confined to the home. For respectable women, being at home is a symbol of dignity, but Dalit women are viewed as being sexually accessible since they left the home to go to work, which goes against who they are supposed to be as deviant women (Chakravarty, 1993.)

Dalit women carry the stigma of being untouchable and pose a challenge to the established order since their bodies are ‘polluted‘ and are not intended to be touched openly in public as doing so would taint society. Ironically, the same body turns into a consumable body that can be controlled and imprisoned by the same hierarchical society that usually criticises the bodies. Thus, Dalit corpses are shown on the screen as examples of abstract labour.

In addition to being governed by upper caste norms and laws, the state’s policies discriminate against Dalit women and are controlling their sexuality. The ban on bar dancers in Maharashtra was enacted in the name of “good governance” which claims that bar dancers are immoral and just want money from the young men they dance for.

As a consequence, these women are responsible for breaking up families and the agony of good wives. This reveals the underlying prejudice of the state’s concept that lowered caste women’s sexuality is dangerous to “Hindu familial Ideology” which is inherently biased towards upper caste people (Dalwai, 2013.)

Here, the government is not outlawing bar dancers due to the extent to which this industry relies on caste-based women labour who are subject to oppression, brutality, and stigma by upper caste men rather, the government is outlawing bar dancers due to the same caste bias to protect the defenceless youth who harass and exploit these women in bars.

The Maharashtra government makes an effort to reproduce the caste-based hierarchy between males from upper and lowered caste women. Here, the state perpetuates discrimination against Dalit women in the labour force based on their caste. The same state forced these women into prostitution and employed them as orchestra dancers to woo male votes for the political parties during the election campaign.

Cinematic mystification of Dalit women’s vulnerability

Hence the weight of caste-based sexual labour falls on Dalit women, leading to vulnerabilities arising from the confluence of caste, labour, and gender that are not sufficiently shown in Indian cinema. Contrary to what is shown in Indian films, the challenges and persecution faced by bar dancers are miserable, and their lives end in the same way. Even laws restricting bar dancers to Dalit women alone do not prohibit the sexualisation of bar dancers in films and item songs.

Actresses who portrayed bar dancers in songs were praised for their acts and made judges on several reality dance competition series, like Malaika Arora and Nora Fatehi. Whereas in real performers, women are exposed to shame and disgrace, their artistic ability to dance makes them the target of lust and desire for males. Here, Dalit women are portrayed as morally corrupt and rebellious individuals whose sexuality is both stigmatised and devoured. Dalit women’s experiences of caste exploitation and oppression are reproduced and mystified at the same time.

Indian Cinema plays central in obscuring the struggle of Dalit women in the guise of class and economic contingency and overlooks the structural systematic penetration of caste prejudices in making Dalit women Bar/ Lavani/ Orchestra dancers and prostitution. As a result, the insufficient representation of bar dancers in Indian films concealed the practices of exploitation and caste-based prejudice against them.

References

1. Dalwai, Sameena. (2013). Cate and Bar Dancer. Economically and Politically Weekly.

2. Gopal, Meena. (2012). Caste, sexuality, and labour: The troubled connection. Current Sociology – CURR SOCIAL. 60. 222-238. 10.1177/0011392111429223.

3. Pal, Bidisha; Bhattacharjee, Partha; and Tripathi, Priyanka (2021). Gendered and Casteist Body: Cast(e)ing and Castigating the Female Body in select Bollywood Films. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 22(10), 57-67.

4. Chakravarti, U. (1993). Conceptualising Brahmanical Patriarchy in Early India: Gender, Caste, Class, and State. Economic and Political Weekly, 28(14), 579–585.

5. Pail, Shailaja, (2022). The Vulgarity of Caste: Dalits, Sexuality, and Humanity in Modern India. Stanford University Press