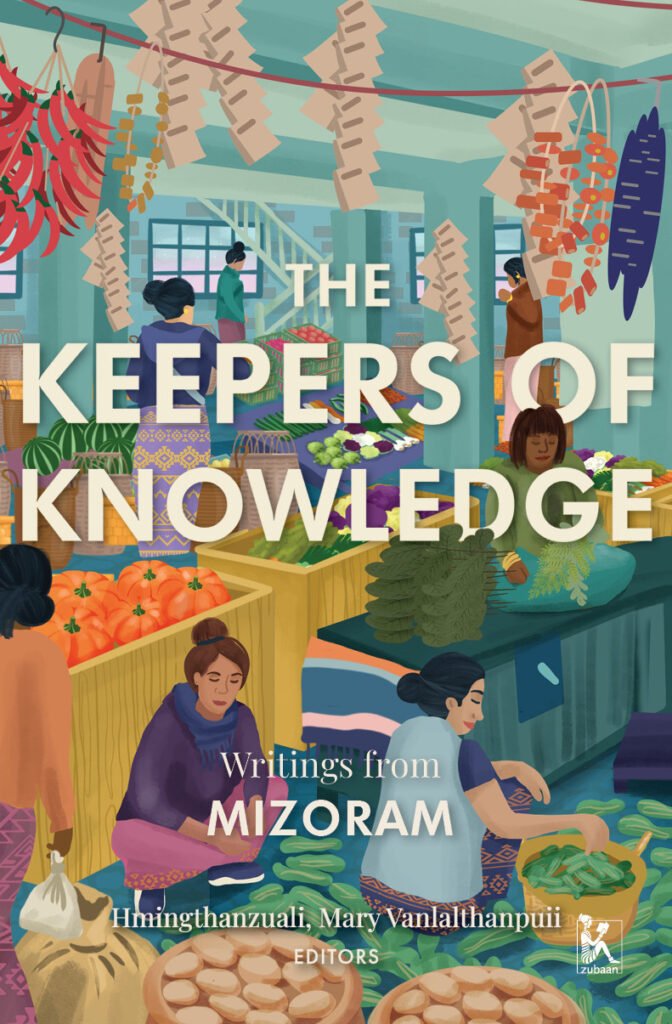

The riot of colours on the book cover of The Keepers Of Knowledge: Writings From Mizoram makes the reader pause at the precision with which Nori Norbhu illustrates a busy market scene, full of women. Evoking the familiar picture of the Ima market of Manipur, the book cover seems to proclaim the need to look into commonplace lives in order to understand how women have been consistently contributing towards the making of society- be it economically or in the domains of knowledge production.

The Keepers Of Knowledge: Writings From Mizoram by Hmingthanzuali and Mary Vanlalthanpuii begins with an introduction, that strikes at the patriarchal ideas reflected in proverbs or oral literature of the Mizo community to ponder on how patriarchal practices of knowledge production have dominated Mizo society through generations. As such women’s roles in such practices have been easily wiped out. Instead of focusing on women’s resistance against such invisibilsation, knowledge practices have handed down the complacent idea of Mizo women as social complaints.

The anthology, therefore, intends to defuse such narratives by unearthing women’s contribution to knowledge production that has often been left out of the bound of anthology-making considering women’s works as insignificant.

The book weaves essays, poems, stories and narratives, translations, research papers, and visual art by women writers and artists from Mizoram, with, essentially, women as the subject.

Section-I puts together critical essays which revolve around issues like the transition of fashion for women in the Mizo society, the development of the Mizo culture of songs, the social and cultural practices around food, the roles played by women in missionary activities across the region, all of which are intricately linked to the shaping of the social and cultural identity of Mizo women.

The articles also zoom into how Mizo folktales, a government-commissioned monograph by J. Shakespear, and the magazine Agape contributed in spreading the knowledge of Christianity among women within the church which led towards their emancipation. We come to know about personalities like Nuchchungi, who was the first Mizo to document folktales, curate Mizo games and songs from yesteryears, and also contribute towards the development of children’s literature and women’s empowerment in Mizoram.

Reflecting on how cancer-affected women’s bodies become sites of double suffering owing to the disease and the gendered stigma attached to the transformation of such bodies, and the need for the building up of an inclusive society that is constituted of people with different sexual orientations, the articles also try to abreast us with the everyday negotiations that such people undergo in Mizo society while suggesting some relevant way out.

Reflecting on how cancer-affected women’s bodies become sites of double suffering owing to the disease and the gendered stigma attached to the transformation of such bodies, and the need for the building up of an inclusive society that is constituted of people with different sexual orientations, the articles also try to abreast us with the everyday negotiations that such people undergo in Mizo society while suggesting some relevant way out.

Section-II curates poems by women poets of Mizoram on themes like the life of a Mizo urban girl who is unaware of the lives of rural women, the heart-rending experiences of the society during Covid lockdown, minor but significant resistances within the home space, confrontation of the Mizo community with the idea of the nation thrust upon them, and most importantly, negotiations with the self. The simple, commonplace language of the poems makes these compositions readable by anyone.

The everyday experiences of women depicted in the poems transform these into a medium of reflecting on the Mizo society in particular, while also making them relevant for the society at large. These thought-provoking pieces induce self-reflection in the reader who is unable to miss how the language, images, and metaphors in the poems, drawn from everyday life, stand as resistance against the elitist, masculinist language of poetry that is often targeted towards a limited readership.

The everyday experiences of women depicted in the poems transform these into a medium of reflecting on the Mizo society in particular, while also making them relevant for the society at large. These thought-provoking pieces induce self-reflection in the reader who is unable to miss how the language, images, and metaphors in the poems, drawn from everyday life, stand as resistance against the elitist, masculinist language of poetry that is often targeted towards a limited readership.

Section-III puts together stories and narratives that meander from personal accounts to imaginative depictions, or even meditative musings, often exuding the warmth of story-telling by the hearth. Moving between past and present, the pieces ponder on issues that affect the lives of women in the conservative, patriarchal Mizo society where the local vocabulary incorporates words and phrases, like ‘uire na’, ‘nuthlawi’, which are reflective of the volatile position of women in the society. The stories use the gendered lens to evoke the complicated meanings of social practices, whether in urban and rural Mizoram, that often make women stand at the edge.

As one of the most engrossing sections of the anthology, here readers will find stories that evoke the atrocities of the Rambuai period, fictionalise the historic tale of Pi Hmuaki, reflect on disrupted lives of women facing psychological, physical and societal abuse, and speak of the tussle between generations of women as they approach the vagaries of life and living. While older women accept the circumstances hurled at them by the society, contemporary women are faced with dilemma when they detect the contradictions inherent in the idea of progress in a society that does not do much to change itself.

However, these are stories of hope, that weave together various paths of resistance adopted by women to overcome the tiring situations, often resorting to the recognition of courage, compassion and love within themselves as a means of bringing about the necessary change in society.

Section-IV comprises of translations of stories, poems, and personal narratives which tell us about the life of Zopari who finds hope amidst the struggles of her life, the experiences of a woman volunteer during the Rambuai period, the outcry of the oppressed against those who soak up power to subdue their own brothers and ravage the land, and a song that glorifies the valour of the great chieftainess, Ropuliani, who resisted British colonial forces until her last breath. These works, flavoured with Mizo myths and cultural intricacies, contribute immensely to the larger framework of women’s contribution towards the making of Mizo culture and heritage.

One of the essays reads the memoirs of B. Vanlalzari, an underground volunteer of the Rambuan period, who was captured by the Indian army as an insurgent. It reflects on Zari’s vehement protest against the social and psychological atrocities of her own community that misrepresents women like herself as promiscuous in the history of the region, thereby making their struggles for the cause insignificant.

Section V has two essays that are shortened versions of research papers originally written as part of the Zubaan-Sasakawa Peace Foundation fellowship. One of the essays reads the memoirs of B. Vanlalzari, an underground volunteer of the Rambuan period, who was captured by the Indian army as an insurgent. It reflects on Zari’s vehement protest against the social and psychological atrocities of her own community that misrepresents women like herself as promiscuous in the history of the region, thereby making their struggles for the cause insignificant. Another essay is based on personal interviews with ten surviving women volunteers of the MNF underground movement which maps the often invisibilised experiences, inspirations and hardships of women during the movement and also how the movement transformed them as individuals.

As a befitting conclusion to this anthology, section VI uses paintings by women artists of Mizoram to depict women’s lives in Mizo folk traditions like that of the lake Rihdil, the atrocities on women during the troubled times of Rambuai, Mizo history that has seen the rise of the chieftainess like Ropuiliani, women involved in the preservation of Mizo heritage like weaving the traditional cloth, Puanchei, besides depicting how contemporary women search for emancipation despite the constraints gripping her like heavy metal bars, like clouds of doubts, like dissipating dreams. The hills, that embrace the land, are where she might find her happiness, as she has in her the mettle of the hills.

This anthology, edited by Hmingthanzuali and Mary Vanlalthanpuii, is a well-woven tapestry of women, as keepers of knowledge thereby fulfilling its objective in resisting the male-dominated practices of anthologising which often invisibilise the contribution of women in canon formation.

This anthology, edited by Hmingthanzuali and Mary Vanlalthanpuii, is a well-woven tapestry of women, as keepers of knowledge thereby fulfilling its objective in resisting the male-dominated practices of anthologising which often invisibilise the contribution of women in canon formation. Although writing is an act of privilege and trying to uphold women’s world through writing already begins with its own limitations, the editors deserve credit in the way they have chosen their contributors who identify themselves as mothers, restauranters, daughters, super-cool aunts, avid gardeners, jewellery makers besides also being active in academia.

This diversity in women contributors is a resistance against the exclusiveness that academia inheres to. Again, the selection also rules out the new form of elitism that has cropped up nowadays that sneers at academia as a space that should be avoided. Academia provides the much-needed social, cultural and economic capital for many women to create a space to voice their concerns, who would otherwise have to remain silent allowing the enterprise of women’s writing to grow within only a few women having inherited resources.

The upkeep of knowledge is safe in the hands of such keepers who embrace themselves unapologetically. Despite being the first of its kind, the anthology thus brings forward a new feminist idiom, where resistance is wrapped in care and compassion, from a land steeped in patriarchy and having a history of armed conflict. The pieces can attract both an investment and a casual reader interested in the life and living of women in Mizoram, thereby targeting an inclusive readership. This anthology befittingly sits with similar works complied on Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Manipur by Zubaan, thus forwarding the vision of this independent feminist publishing house towards unearthing the less-heard voices of women from the peripheries.

About the author(s)

Priyanka Chatterjee is a mother, researcher, and academic. She lives and writes from Siliguri. Her articles have appeared in Feminism in India, LiveWire, Himal Southasian, Sikkim Express, among others. She can be reached at site.surferpc@gmail.com and is on Instagram @priz_chatt

Wonderful to read this, thank you for writing the review. I want to leave 2 suggestions though. 1) I’m not sure if you intentionally put the photos from across the North East states in your article, but if not, only two photos are actually those of MIzos in Mizoram. 2) The 20 years of conflict in Mizoram is called ‘Rambuai’, rather then ‘Rambuan’, small typo but it changed a whole lot of meaning. Thanks

Thank you for your suggestions. Firstly, as you know writers are not responsible for the pictures the magazine uses in the articles, until writers claim credit for the same. So, I hope the magazine will surely take your suggestion into account the next time. Secondly, yes, the spelling of ‘Rambuai’ is a slip not intentionally caused as you might have noticed the proper spelling in the rest of the article. I hope the slip may be seen as a human error and not lightness of intention and research behind the piece. Thank you for your engagement and for reading the review. Means a lot.