Natasha Behl’s Gendered Citizenship: Unveiling the Enigma of Gender-Based Discrimination, Exclusion, and Violence in India, delves into the perplexing paradox surrounding the prevalence of such societal ills despite the Indian constitution’s foundation of an all-embracing democracy dedicated to upholding gender equality. Published by Oxford University Press in 2019, this work seeks to unravel the enigmatic forces that fuel gendered violence within the democratic fabric of India.

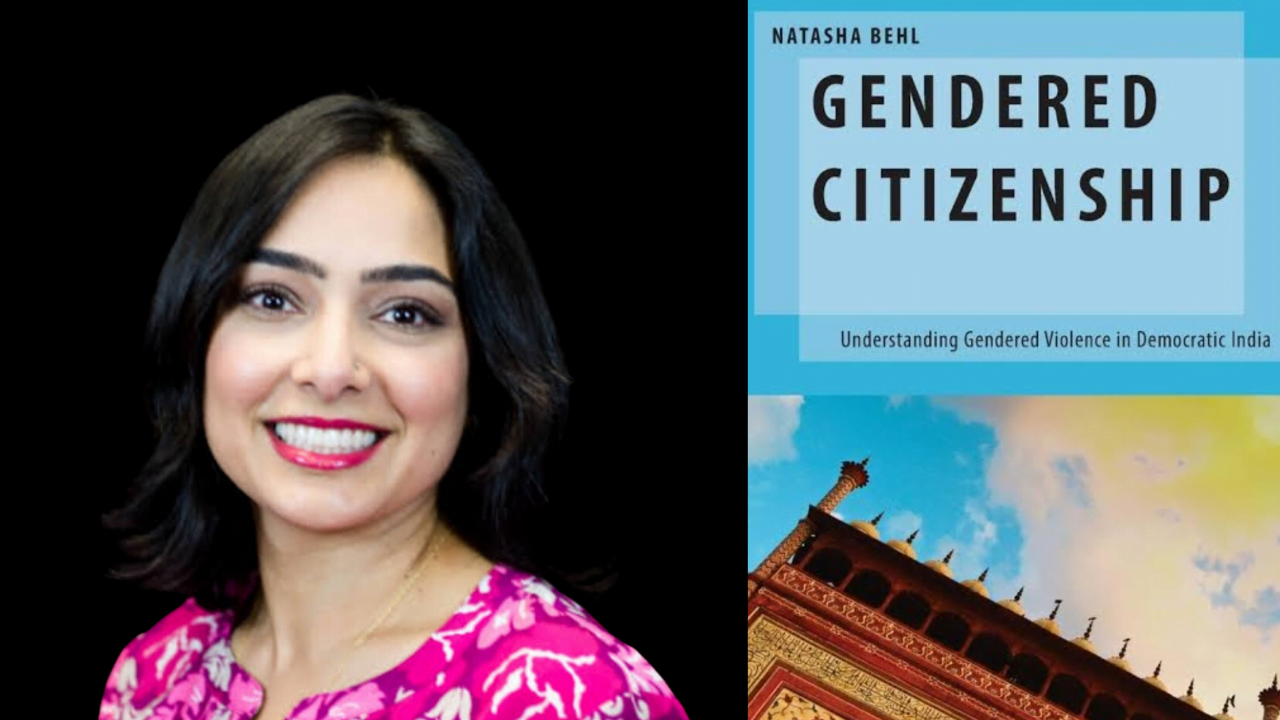

Natasha Behl is the Associate Professor in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University. Dr. Behl completed her doctorate in political science at the University of California, Los Angeles, where her training focused on race, ethnicity, politics and comparative politics. In this book, Behl employs an ethnographic methodology to delve into the lived experiences of women within the public spheres of the country.

By critically examining the purported liberal ideals of Indian democracy, Behl sheds light on the pervasive gender-based violence and exclusion that persist within society. She highlights the paradoxical situation faced by Indian women, who may be visible in various public forums and institutions, yet are perpetually caught in a complex web of inclusion and exclusion.

Through this approach, she unveils the intricate processes of meaning-making and self-reflexivity that these women engage in. By critically examining the purported liberal ideals of Indian democracy, Behl sheds light on the pervasive gender-based violence and exclusion that persist within society. She highlights the paradoxical situation faced by Indian women, who may be visible in various public forums and institutions, yet are perpetually caught in a complex web of inclusion and exclusion.

In Gendered Citizenship, Behl presents a comprehensive exploration of how citizenship is constructed and experienced differently based on gender. She challenges the notion of citizenship as a neutral and universal concept, arguing that it is deeply entangled with gender hierarchies and power dynamics. The book goes beyond a simplistic understanding of gender and citizenship by emphasising the importance of intersectionality.

She convincingly argues that gender intersects with other social categories, such as race, class, and sexuality, shaping individuals’ experiences in complex and interconnected ways. By acknowledging these multiple dimensions of identity, Behl exposes the intersecting systems of power and privilege that influence citizenship. This nuanced approach challenges essentialist notions of gender and highlights the need for an inclusive and intersectional understanding of citizenship.

The book begins by establishing a theoretical framework for understanding gendered citizenship. Behl draws on feminist theory and concepts such as intersectionality to analyse how gender intersects with other social categories like race, class, and sexuality. She emphasises the importance of recognising the multiple dimensions of identity and how they shape individuals’ experiences of citizenship.

The book begins by establishing a theoretical framework for understanding gendered citizenship. Behl draws on feminist theory and concepts such as intersectionality to analyse how gender intersects with other social categories like race, class, and sexuality. She emphasises the importance of recognising the multiple dimensions of identity and how they shape individuals’ experiences of citizenship.

The book presents a captivating exploration of democracy, citizenship, religion, and gender in the context of Indian democracy, challenging long-held academic assumptions. Behl addresses a gap in the existing literature on citizenship by introducing the concept of situated citizenship, which enables empirical analysis of exclusionary inclusion across various contexts. By emphasising that citizenship encompasses not only a fixed legal status but also a social relationship shaped by specific circumstances, Behl highlights how disparate and unequal experiences are perpetuated, questioned, and resisted in both public and private spheres.

These experiences are often compounded by factors such as gender, caste, class, religion, and nationality. Behl asserts that the framework of situated citizenship and exclusionary inclusion has broader applicability in understanding the realities of unequal democracy in any part of the world, but it particularly sheds light on the gender-based inequities experienced in India.

Behl explores the structural barriers and societal norms that hinder the translation of constitutional provisions into meaningful change. She examines the ways in which patriarchal power structures and cultural norms continue to shape gendered experiences within the public sphere, despite legal guarantees of equality.

The book highlights the complexities and challenges that hinder the realisation of true gender equality, despite constitutional provisions for gendered equality. One aspect that Behl addresses is the gap between constitutional provisions and their effective implementation. While the Indian Constitution guarantees gender equality, the actual realisation of these rights and protections remains a challenge. Behl explores the structural barriers and societal norms that hinder the translation of constitutional provisions into meaningful change. She examines the ways in which patriarchal power structures and cultural norms continue to shape gendered experiences within the public sphere, despite legal guarantees of equality.

One of Behl’s key arguments is that a focus solely on increasing women’s representation in politics fails to address the underlying power structures and systemic barriers that perpetuate gender inequality. While having more women in political positions can bring diverse perspectives and experiences to the decision-making process, it does not guarantee that these women will challenge or change the existing gender norms and power dynamics.

Behl argues that simply having women in political positions does not automatically lead to gender-sensitive policies or a transformative impact on gendered citizenship. She highlights the limitations of representation within existing political systems and argues that women who attain political positions often have to navigate male-dominated spaces and adhere to existing norms and practices to maintain their positions. This can restrict their ability to advocate for feminist agendas or challenge existing power structures. Furthermore, the focus on increasing women’s representation can sometimes reinforce the notion that women’s issues are separate from broader social and political issues, relegating them to a narrow gendered lens rather than integrating gender perspectives into all policy areas.

Instead of solely focusing on increasing women’s representation, Behl calls for a more comprehensive approach to gendered equality. This includes challenging and transforming the underlying power structures and norms that perpetuate gender inequality, fostering an inclusive and intersectional understanding of gendered citizenship, and working towards systemic changes that address the multiple dimensions of discrimination. Behl advocates for a holistic approach that integrates gender perspectives into all policy areas, promotes gender-sensitive education, and supports broader social movements for gender equality.

Behl’s argument acknowledges that religious institutions often uphold patriarchal norms and practices that limit women’s rights and participation. However, the author also explores instances where women have found spaces for empowerment and agency within religious institutions. She recognises that religious practices and beliefs are multifaceted and can be interpreted and implemented in diverse ways.

Behl’s argument acknowledges that religious institutions often uphold patriarchal norms and practices that limit women’s rights and participation. However, the author also explores instances where women have found spaces for empowerment and agency within religious institutions. She recognises that religious practices and beliefs are multifaceted and can be interpreted and implemented in diverse ways. In some cases such as Sikh women, they have been able to challenge traditional gender roles and norms within religious contexts and negotiate for greater equality and rights.

The examination and study of Sikh women’s experiences within gendered citizenship underscore the complexities and nuances of their agency and resistance. The book recognizes the importance of both religious and cultural frameworks in shaping Sikh women’s lives and acknowledges the ways in which Sikh women challenge and negotiate gender inequalities within these contexts.

Throughout the book, Behl challenges conventional notions of citizenship and invites readers to critically examine the inherent gender biases within existing political systems. She challenges the narrow and exclusionary notion of citizenship often prompted by majoritarian politics and emphasises the importance of recognising diverse forms of citizenship that go beyond legal frameworks which invoke the readers to rethink the boundaries of citizenship. The book is an essential read for anyone seeking a comprehensive understanding of gender, identity, and power within the context of citizenship.

About the author(s)

Aamir Raza is a dedicated researcher based in New Delhi, India. He holds a Master's degree in Political Science from Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi. He has been previously associated with Lokniti-CSDS and the Institute of Perception Studies as a Researcher. His areas of research interest include Electoral politics, representation, minority studies, ethnic politics and democratisation.