Over the last two centuries, India has witnessed a myriad of battles fought against the deeply entrenched institution of caste, which has long defined its public life. These struggles are woven with narratives of both tragedy and humour, valour and deceit, bigotry and humanity. They have left their mark on the annals of history, meticulously recorded through the debates that unfolded in courts, legislative assemblies, and government chambers. Notably, while other communities in India were also affected by the caste system, the legal initiatives to reform it primarily involved Hindus, given its religious origins.

Paradoxically, despite the significance of these confrontations against the deeply ingrained prejudice in Indian society, they have, to a certain extent, been understudied or even disregarded within the existing body of literature. This omission is indeed perplexing, considering the transformative impact of resultant reforms, albeit imperfect, on all castes, affecting them to varying degrees and in diverse forms.

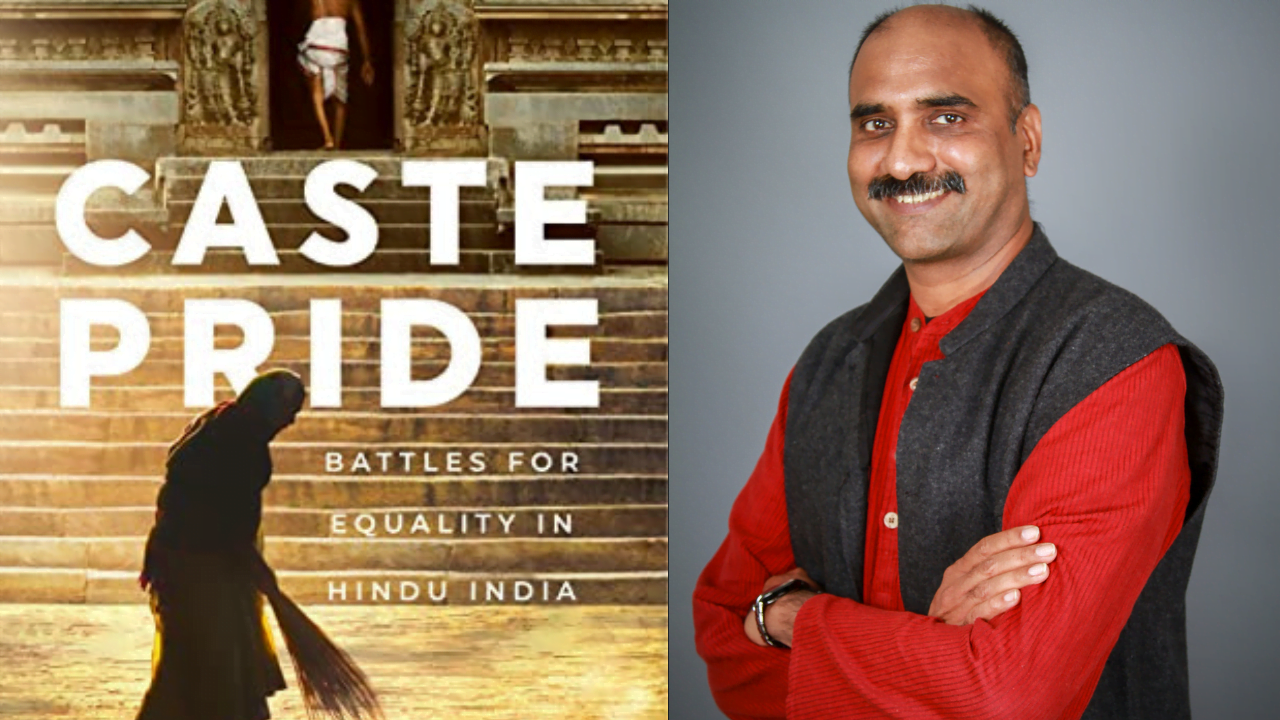

The book under review ‘Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India,’ by Manoj Mitta a senior Journalist and former editor captures such omissions and delves into the intricate interplay between caste and the legal system. This work elucidates how legal frameworks often bolstered the influence of caste, how constitutional law strived to mitigate its constraints, and how the enduring power of caste persistently tests and surpasses legal structures. It illuminates an ongoing struggle between the entrenched forces of caste and the ideals enshrined in the constitutional conception of law.

This book is organised thematically, tracing the evolution of socio-legal reforms intended to prioritise shared humanity over outdated notions of purity and pollution. Despite the challenges these measures faced, their impact has been limited, with some even proving counterproductive. The 1950 abolition of untouchability, despite its lofty rhetoric, ironically led to increased violence against those formally emancipated from erstwhile untouchability. This resulted in new forms of atrocities, particularly mass killings as a response from dominant castes.

The first acknowledged massacre of this kind occurred in 1968 at Kilvenmani, within what was then known as the Madras state. Subsequent courts consistently acquitted the accused of homicide charges, establishing a template for impunity. Even in cases where justice was served, such as the 2006 Khairlanji massacre in Maharashtra, courts hesitated to acknowledge the caste aspect. The dysfunction of legal safeguards is a clear reflection of the persistent violence ingrained in caste-based inequality. Impunity is just one facet of this systemic problem. Despite various disguises, the world’s largest democracy remains deeply entangled in caste-related issues.

In his extensively researched book, Mitta delves into the legislative debates of British India and the early years of independent India. By drawing from forgotten government orders, private papers of key figures, and ordinances, he provides a comprehensive account of the arguments surrounding various legal measures. This work sheds light on the pivotal role of British Indian officialdom, which often set limits on legislative reforms due to concerns about not incurring the disapproval of upper-caste Hindus or the fear of societal disruptions.

Mitta skillfully combines vivid descriptions of legal campaigns with eloquent summaries of court judgments. Notable figures in this narrative include Maneckji Byramji Dadabhoy, a Parsi member of the central legislature, who presented the first resolution in 1916 addressing Dalit grievances. Additionally, Dalit legislators such as R. Veeraian from Madras are highlighted for their unwavering pursuit of equality in public spaces, encompassing roads, markets, and wells.

The book underscores the diversity of individuals and groups advocating against caste-based inequities, encompassing Dalits, Gandhians, liberal Congress members, Hindu reformists, and even a notable Muslim leader, M.A. Jinnah, who advocated for Dalit rights. British official representatives both within and outside the legislature also played a role, each motivated by varying reasons.

Mitta dispels several myths and introduces us to unsung heroes in the caste reform movement. He reveals that even Mahatma Gandhi initially lagged behind his contemporaries and adversaries in recognising and addressing erstwhile untouchability.

In an intriguing twist, he describes how, in 1913, Motilal Nehru, at the peak of his legal career before the Allahabad High Court, defended Brahmins accused in a Sati case. B.R. Ambedkar, despite his brilliance in challenging caste, is shown to have had occasional lapses in understanding its legal aspects.

Prominent Indian National Congress leaders like G.K. Gokhale never directly tackled the issue of caste and untouchability. The likes of Surendra Nath Banerjee and Madan Mohan Malaviya, both former party presidents, opposed the formation of a committee to study erstwhile untouchability. Mitta emphasises that the decision to exclude social reforms from the Congress agenda significantly influenced the conduct of its members, even in their roles as legislators.

The book also pays tribute to lesser-known reformist figures, such as Vithalbhai Patel, B.V. Narasimha Ayyar, Kalicharan Nadagaoli, Hari Singh Gour, M.R. Jayakar, M.C. Rajah, R. Sreenivasan, R. Veerian, S.K. Bole, G.A. Gavai, and Thakur Das Bhargava. It is noted that these individuals remain unsung because they either were not affiliated with the Indian National Congress or if they were, their convictions diverged from the mainstream party consensus.

The author’s scrutiny of mass violence against Dalits, exemplified by cases in Kilvenmani, Tsundur, Bathani Tola, Laxmanpur Bathe, and the tragic “Khairlanji case,” exposes the court’s bias. These incidents reveal how Dalits faced profound hatred and prejudices from the ruling elites, with limited access to justice from the courts. Judicial proceedings in such cases were protracted, neglecting the Dalit victims’ claims while protecting the interests of social elite criminals.

Even in cases like Khairlanji, where Dalit family members were raped, murdered, and lynched, the police mishandled the investigation, caste angles were suppressed, and local media blamed the victims. Only after Dalit civil society protests did the case move to the CBI, resulting in convictions for murder but acquittals for sexual and caste offences. Recent incidents like Hathras demonstrate the continued denial of dignity to Dalit victims.

Mitta’s work critically exposes the historical limitations and deficiencies of modern institutions in delivering relief, security, and justice to the most marginalised social groups. By focusing on legislative debates and court proceedings, it underscores the way colonial and postcolonial elites grappled with the caste question. This starkly contrasts with the more robust anti-caste activism happening outside these institutional spaces, revealing the timidity of upper-caste ‘reformers,’ and the fierce resistance they encountered from conservative elements within their ranks.

This book artfully unravels the intricate interplay between the Hindu caste system and the legal framework, shedding light on the perpetual clash between the foundational principles of equality, fraternity, and liberty, and the deep-rooted social hierarchy of Hindu society. A valuable resource for legal practitioners, historians, and social activists and also an indispensable read for those dedicated to forging an equitable society in India, one that upholds the rights of women and Dalits.

About the author(s)

Aamir Raza is a dedicated researcher based in New Delhi, India. He holds a Master's degree in Political Science from Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi. He has been previously associated with Lokniti-CSDS and the Institute of Perception Studies as a Researcher. His areas of research interest include Electoral politics, representation, minority studies, ethnic politics and democratisation.