Although the term “Intersectionality,” was coined in 1989, by a Feminist Scholar, Kimberly W. Crenshaw, the discussions around intersectional oppression have been promoted in historical writings and are one of the foundations of third-wave feminism.

This article discusses how one of the first published documents about intersectionality, The Combahee River Collective Statement, by a group of black lesbian feminists in the 1970’s changed how feminists thought about social and political equality and freedom, which ultimately led to the third wave.

Intersectionality is defined as “the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalised individuals or groups.” It, therefore, allows us to assess marginalisation from every aspect of someone’s identity. For example, a South Asian abled woman would experience immigration differently than a South Asian woman with a disability.

The wave metaphor that is used in feminist theory gives us a compartmentalised view of how feminism and its definitions have shifted to encompass a larger demographic of marginalised populations throughout the past two centuries. The wave metaphor also allows us to see feminist thinking as a wave of progressive thoughts about women and other genders, not just socially and politically but also, within feminist groups.

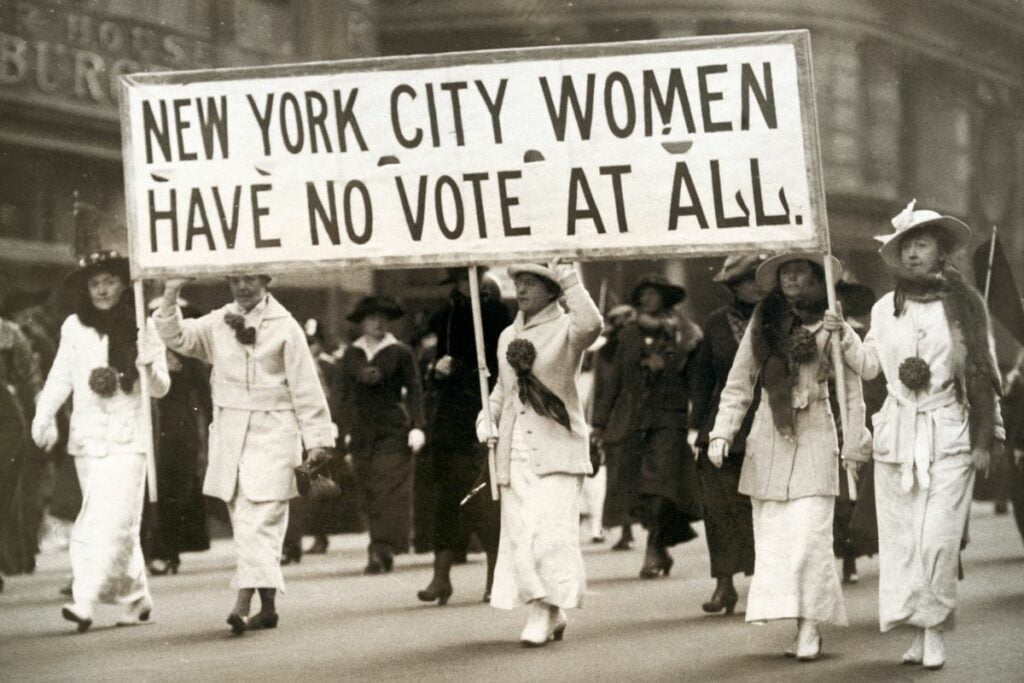

The first wave, although there is no concrete data documented as to when exactly it began, was believed to have begun in the mid-19th century. The goals of first-wave feminists were to attain equality politically. The limelight conversations concerned citizens’ basic rights, such as the right to vote and contributions to the economy. The focus was on the Suffragettes.

The first wave went on till the signing of the 19th Amendment in 1919 granting women the right to vote. Although it granted all women the right to vote, women of colour were still finding it difficult, socially, to do so.

The first wave is often critiqued as “white feminism,” being held accountable for a degree of solipsism regarding women’s rights. The second wave (the 1960s-1970s), however, kicked off with Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique addressing the issues of how women are perceived socially. The book, which resonated with millions of women focussed on the frustrations of middle-class American homemakers, asking for more opportunities economically, and targeting pay gaps.

“I thought there was something wrong with me because I didn’t have an orgasm waxing the kitchen floor,”(Betty Friedan,1970). These goals of social equality became the axis of the second wave.

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was one of the feminist groups during the second wave. Formed in 1974, it was composed of seven members who later drafted the Combahee River Collective Statement in 1977. The statement is still considered a landmark document in the way we think about intersectionality in feminism. It addressed the need for multicultural and multiracial perspectives in feminist theory. Demita Frazier, Beverly Smith, and Barbara Smith were the primary authors of the statement. These were the significant takes of the statement:

- Feminism should be seen as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all Black women face.

- Black Feminism should be recognised as human, ‘levelly human,’ amid concepts of sexual politics, patriarchal rule and white feminism.

- A combined anti-racist and anti-sexist position is necessary to acknowledge, to politically solve the issues of Black Women.

- Racial and Sexual oppression is often experienced simultaneously.

- “Although we are feminists and Lesbians, we feel solidarity with progressive Black men and do not advocate the fractionalisation that white women who are separatists demand.”

- Personal is Political. The experiences faced individually by many women of colour, should not be confused for something domestic and “their own business.” Until all are free of these marginal oppressions, it better be all of our business.

- Through a socialist approach, the work may be organised for the collective benefit of the labour force, and not for the profit of the bosses. However, it was not sure whether a socialist approach would work.

- The real class situation is of the persons for whom racial and sexual oppression are significant determinants in their working/economic lives.

- The difference between sex and gender is that sex is something biological whereas gender is socially constructed. This gives an insight into how gender roles come about and with it, a great deal of separatism. Gender roles and the concrete expectations of them, have socialised us into believing and actively internalising these divides.

- “We do not have racial, sexual, heterosexual, or class privilege to rely upon, nor do we have even the minimal access to resources and power that groups who possess anyone of these types of privilege have.”

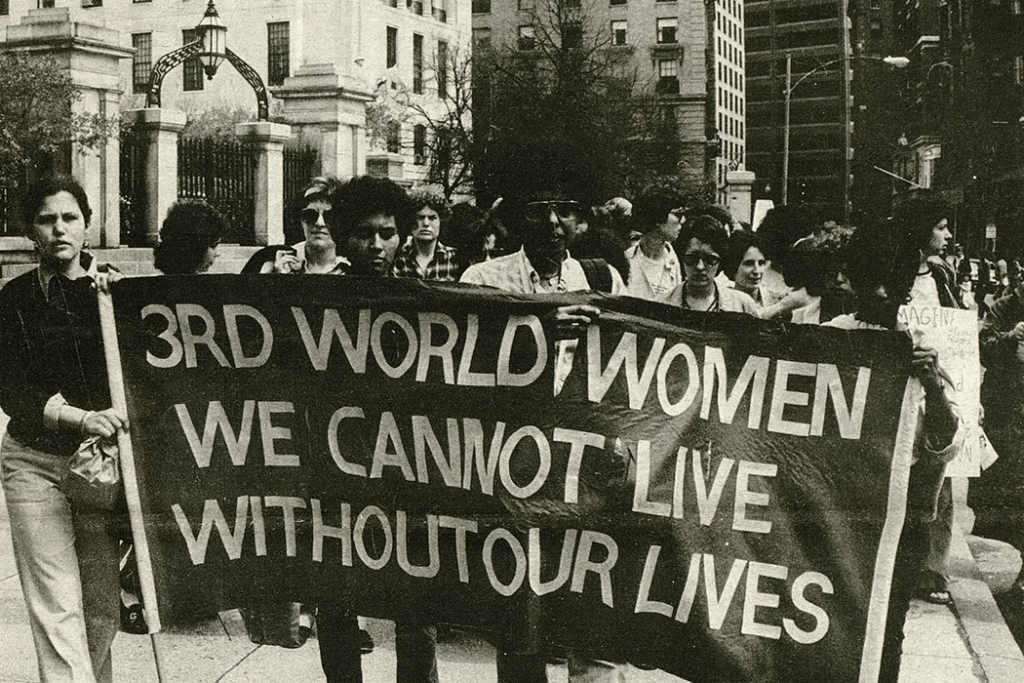

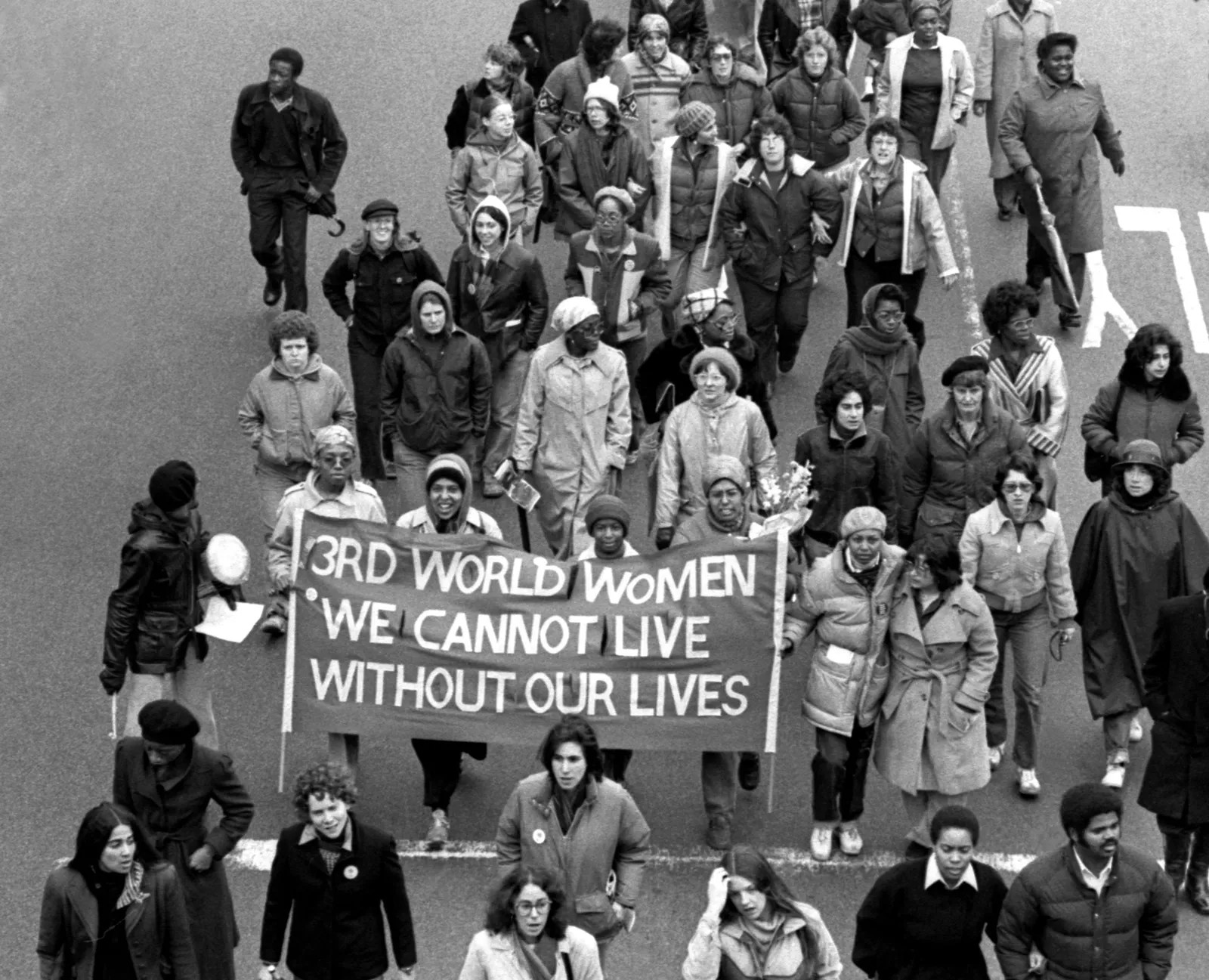

These implications and demands were the core concepts of “Black Feminism,” which later translated into feminism for all women of colour. The analysis of this statement tells us that the second wave was progressively theoretical, based on a nexus of neo-Marxism and Freud’s psycho-analytical theory, and began to associate the subjugation of women with broader levels of patriarchy, capitalism, normative heterosexuality, and the woman’s role as wife and mother. The acknowledgement of these ideas helped change the way we define feminism in the first place.

Feminism is not about the rights of just women, it is a political movement that strives to understand the social structures that separate us and fight against the weight of that social structure, for an equal middle ground, where everyone gets what they inherently deserve, the rights and opportunities that were stripped off of people due to these structures.

The third wave of feminism (1990s – 2010s) largely focussed on multicultural feminism. Multicultural feminism, as central to the CRC Statement, included a diversity of women’s voices and their cultural dogmas. We are currently in the fourth wave. The tool that’s central to this wave is the digitalisation of media.

Feminism is not about the rights of just women, it is a political movement that strives to understand the social structures that separate us and fight against the weight of that social structure, for an equal middle ground, where everyone gets what they inherently deserve, the rights and opportunities that were stripped off of people due to these structures.

With the amplification of issues of assault, sexual violence, sexism, trans-violence, and constricted gender expression, this wave largely encourages the idea of an individualistic sense of self rather than a communal sense of self. Holding ourselves and others accountable is an achievement that digitalisation has helped us with.

With the onset of Pride month this year, lately, the voices of queer people of colour have been largely heard by society, however, many of them remain subdued. The recognition of queer people in ongoing political revolutions like feminism is necessary.

Their deviance from normativity, and hegemonic identities is what helped the Combahee River Collective to discern these manifold issues. Something to take away from that is that the first step to breaking gendered norms is recognising those norms within.

Once we get past the presumptions of our expectations and roles, we can break down our intersecting identities and allow ourselves to be socially decoded because rebellion comes from a strong sense of what is right and how would we know what is right if we don’t know/allow ourselves to be what we are?

About the author(s)

Shivani (she/her) is a student at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. She spends most of her time writing, reading, jamming on her guitar, or exploring new places. She loves documenting small events of her life through any of these mediums. She advocates for LGBTQIA+ rights, domestic and sexual violence, trafficking, gender and race equality and mental health.

This is a very insightful and well written article. Thank you so much Shivani Singh. I am one of the co-authors of the “Combahee River Collective Statement.” There are a couple of points of information I would like to share. There were more than seven members of the Collective. Dozens of women were involved during the life of the collective including those who participated in Black feminist consciousness raising sessions held at the Cambridge Women’s Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Demita Frazier, Beverly Smith, and I were the only co-authors of the statement. I am aware that other sources have described us as the primary writers. The First Wave of the U. S. feminist movement is often considered to have begun with the women’s rights convention held in Seneca Falls, New York on July 19th and 20th,1848.

In solidarity.

Barbara Smith