Trigger Warning: This article discusses religion and caste-based segregation In India and mentions caste-based violence and rape.

A new study titled ‘Residential Segregation and Unequal Access to Local Public Services in India: Evidence from 1.5m Neighborhoods’ has found that Indian cities and villages have sharp segregation based on religious and caste-based lines. It is an ongoing study being conducted by Anjali Adukia of the University of Chicago, Sam Asher of Imperial College, London, Kritarth Jha of Development Data Lab, Paul Novosad of Dartmouth and Brandon Tan, an economist with the International Monetary Fund. The study used two Indian administrative censuses as their primary data- The Socioeconomic and Caste Census (SECC, 2012) and the Indian Economic Census.

The study focussed on both urban and rural areas, studying segregation and its impact on Scheduled Caste and Muslim neighbourhoods. The reason it picked these two groups is that they are both, in their own ways, historically oppressed minorities in the upper caste Hindu dominant society of India. Both groups are victims of generational deprivation, something this study has further proven. There have also been recent cases of violence against both.

Many studies have shown that caste and religious discrimination exists as much in the city as in the village, taking different forms. Moreover, it was found that neighbourhoods, where Schedule Caste people and Muslims were concentrated were located strategically away from public schools, hospitals and other facilities.

Just in the past two weeks, a Dalit man’s thumb was chopped off in Gujarat, a Dalit woman was gang-raped and murdered in Rajasthan, and a Dalit man was brutally attacked in Uttar Pradesh. Similarly, Muslim auto drivers are facing violence in Kolhapur, Maharashtra, a group of Muslims was forced to flee a small town in Uttarakhand, and a Hindutva leader called for violence against Muslims in Chhattisgarh. So the oppression of both these groups is evident.

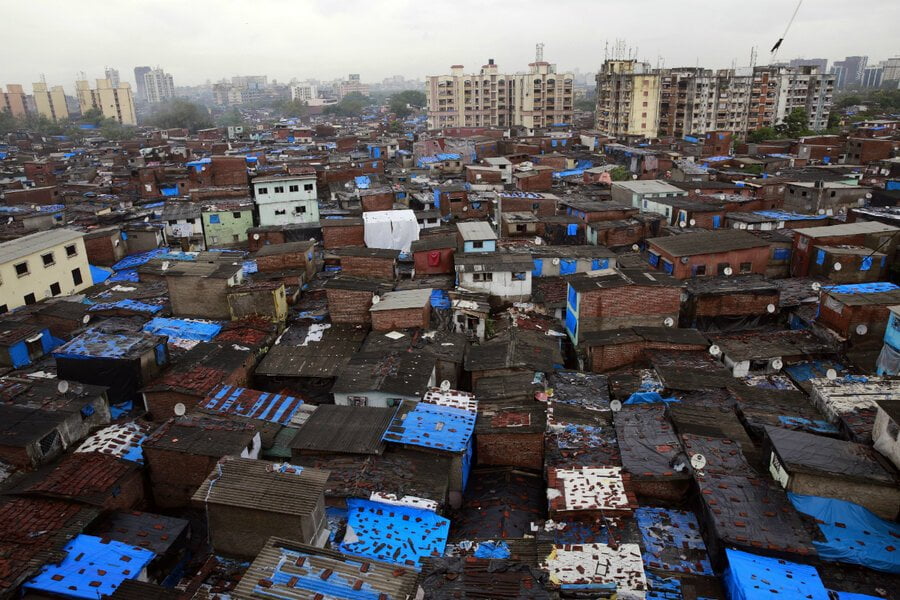

The study found that segregation in the cities on caste and religious lines replicated the patterns thought to have been left behind in ‘backward’ rural areas. Many studies have shown that caste and religious discrimination exists as much in the city as in the village, taking different forms. Moreover, it was found that neighbourhoods, where Schedule Caste people and Muslims were concentrated were located strategically away from public schools, hospitals and other facilities.

As the study stated, “The concentration of marginalised social groups into poorer neighbourhoods is understood to be a major driver of the intergenerational persistence of cross-group inequality in many contexts.” Neighbourhoods are generally viewed as the starting point to access employment and resources and form connections for educational opportunities.

When a neighbourhood lacks these facilities, it can deprive the residents of these opportunities. Moreover, residential patterns are highly persistent, which makes these inequalities challenging to address. The study said, “Indian cities are replicating the social group settlement patterns that have been in place for hundreds of years in villages.”

The study found that, on average, SCs are similarly segregated to Black people in the United States, while Muslims are less segregated. However, even though Muslims are less segregated than SCs on average, Muslim neighbourhoods are more highly segregated- that is, Muslim neighbourhoods are more likely to be entirely Muslim. It was also found that Muslims were more segregated in urban areas, while SCs were more segregated in rural areas.

Another discovery was that access to public facilities such as schools, hospitals, and sanitation facilities was universally worse for Muslim neighbourhoods than SC neighbourhoods. All people growing up in marginalised group neighbourhoods, whether they belong to that group or not, were found to have worse educational incomes.

Segregated cities, on average, were found to be poorer than non-segregated cities. It was found that the north and south of India were about equally segregated. The study found that “An individual in a Muslim enclave is predicted to obtain about 0.1 fewer years of education than an individual in an integrated neighbourhood.”

Segregated cities, on average, were found to be poorer than non-segregated cities. It was found that the north and south of India were about equally segregated. The study found that “An individual in a Muslim enclave is predicted to obtain about 0.1 fewer years of education than an individual in an integrated neighbourhood.”

The study also says that “raising the Muslim share of a neighbourhood by 50 percentage points is associated with a 28% lower likelihood of the neighbourhood having a public secondary school”. Another fact is that “A 100% Muslim neighbourhood is estimated to have 2.2 fewer primary schools per 100,000 people than a 0% Muslim neighbourhood”. This clearly shows the adversely negative impact of having segregated neighbourhoods. Then how has this gone unnoticed?

This is because policymakers usually analyse accessibility through a larger lens, such as the district. Allocations of schools and hospitals are more or less even across districts. But within towns and villages, the distribution of schools and hospitals across neighbourhoods is highly unequal, undoing the work of policies created at higher levels of government. So when analysed by district, these inequalities do not show up. It is only when we zoom in on the neighbourhood that these patterns of segregation become visible.

One of the reasons it is so alarming that the segregation in India is comparable to the USA is that the USA has had an official policy of redlining. Redlining was an American policy that outlined neighbourhoods majorly occupied by African-American citizens and denied home loans to people living there, forcing them to stay within the “red lines.” The segregation resulting from those policies is visible even today.

One of the reasons it is so alarming that the segregation in India is comparable to the USA is that the USA has had an official policy of redlining. Redlining was an American policy that outlined neighbourhoods majorly occupied by African-American citizens and denied home loans to people living there, forcing them to stay within the “red lines.” The segregation resulting from those policies is visible even today. However, modern India has never had the government regulations such as redlining, yet segregation has persisted at similar levels- which is a cause for concern.

In India, segregation is not a policy issue. Segregation in India is more because of discrimination in both public and private housing, which the judiciary has explicitly ignored. However, we can still refer to American history to understand why segregated neighbourhoods face adversity. As the study said, “The most obvious explanation for both of these phenomena is that suggested by the U.S. literature: that state and private discrimination drives minorities into segregated neighbourhoods, which are then under-serviced with public facilities.”

Towards the end of the study was a horrifying prediction made by the researchers. “Younger cities in our sample are less segregated than older cities, but the pace of change is glacial; at this rate, India’s Muslims and Scheduled Castes will not be integrated into cities for another 500 years.” Considering the impact that segregation has, and the dystopia it signals, this study should get the attention it needs.

About the author(s)

Jyni Verma is a writer with a focus on gender, intersectionality, social justice issues and cultural analysis. They are currently pursuing their masters in sociology at Jamia Millia Islamia.