Caste as Social Capital: The Complex Place of Caste in Indian Society (published by Penguin Random House India, 2023) is a research-based book packed with statistical data on caste compositions in India across various sectors, primarily – education, entrepreneurship, and services. The author R. Vaidyanathan aims to bring forth the merit of perceiving the “age-old institution” of caste as “social capital” and thereby shining a “positive” light on the role caste can play in the economic sphere comprising markets and workforce.

The author’s attempt to prove how caste communities have been moving up the economic ladder through the years and, across industries, be it agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and services is well-intentioned. However, greater numbers do not necessarily always translate into or automatically mean greater social justice and lesser discrimination or exploitation.

‘Vaishyavization’ of India

While endorsing the need to move toward the concept of Vaishyavization of India, Vaidyanathan argues, “…the time has come for the government to perform mainly the task of a Kshatriya (internal and external security) and encourage large segments of our society to become Vaishyas through instrumentalities of credit delivery, taxation, social security and development of regional and community-based clusters.”

Within the paradigm of caste communities, the author appears selective in underlining the merits of the Indian “commercial castes”, namely – the Marwaris, Jains, Bohras, Chettiars, and so on. Unfortunately, the book does little to investigate the socio-economic status of Dalits, Bahujans, and Adivasis.

This is how the social status of minorities can “enhance”, or so, believes the author. Well-intentioned, albeit wishful, such an argument relies heavily on the strength of credit, capital, and upward financial mobility in erasing the ills of social ostracism and stigma based on caste identity. Second, it seems that the author is primarily dealing with the potential of what he terms “white-collar castes” and how the rest of India must strive to emulate the rigour and promise shown by the SC, ST, and OBC communities in the white-collar job market.

Within the paradigm of caste communities, the author appears selective in underlining the merits of the Indian “commercial castes”, namely – the Marwaris, Jains, Bohras, Chettiars, and so on. Unfortunately, the book does little to investigate the socio-economic status of Dalits, Bahujans, and Adivasis.

Caste through the lens of economics

While giving a lowdown on how the first census of 1881, conducted by British officials led to hierarchies and unfair gradation in caste, and later, the Mandal Commission of the 1980s somehow “overestimated” the OBC population (based on the 1931 census), resulting in elevated percentages in reservation ceiling, the author makes a valid plea for a detailed “caste-wise census” so that accurate steps can be taken and affirmative action policies designed in the sectors of education and employment.

The author makes it clear that in his book, caste would be examined through the lens of business, economics, and entrepreneurship, and that he would deliberately keep away from the religious, social, and political perspectives since these have been studied amply. And this is where the research agenda seems a bit misleading and misplaced. Why so? Because hierarchies present in the caste compositions do not operate in isolation.

To understand caste strictly from the prism of economy and business is limiting, and somewhere fails to take into account the influence of religious, social, and political equations and dynamics. These are overlapping categories that intersect according to particular socio-cultural contexts.

To understand caste strictly from the prism of economy and business is limiting, and somewhere fails to take into account the influence of religious, social, and political equations and dynamics. These are overlapping categories that intersect according to particular socio-cultural contexts.

Let us take the example of manual scavenging. According to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, 58,098 manual scavengers were identified and caste-related (category-wise) data were available with reference to 43,797 manual scavengers (PIB, 2021). The report ends with this statement: “There is no proposal to provide educational and professional reservation for their rehabilitation.”

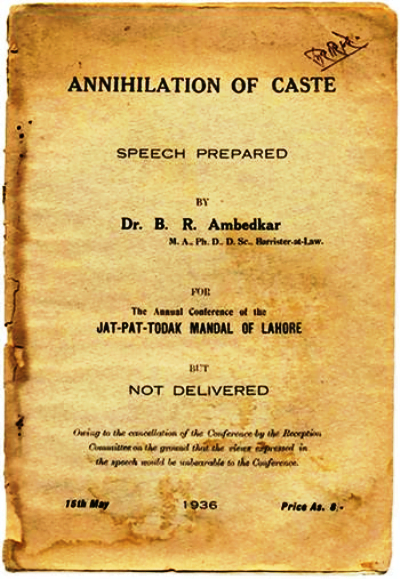

If “the duties of a Brahmin and a Dalit” had “equal merit before God”, as explained by Mahatma Gandhi on how the ‘varna’ system is premised on a ‘just system of equal duties’ – why is it that the most lowly, menial, dirty, even life-threatening jobs are reserved for the lower strata of society? This is precisely what Dr. B.R. Ambedkar critiques while foregrounding the dehumanising aspects of the hierarchical caste system in The Annihilation of Caste (1936). Ambedkar envisions a society where the undisputed and absolute “sanctity” (Mclaughlan, 2022) and ‘authority’ of the Shastras would be challenged and demystified so that a progressive, morally strong, and modern nation could emerge.

So, how and where can the model of ‘Vaishyavization’ be incorporated into the socio-economic uplift of the community of manual scavengers, sanitation workers, garbage collectors, cleaners and sweepers? For a Dalit woman, the oppression would be twice- or thrice-fold because of her gender and caste status. For Dalit Muslims, the barriers of subjugation and structural inequality are layered and more complex.

The author quotes sociologist Dipankar Gupta when he argues, “there are probably as many hierarchies as there are castes in India,” but the caste order that he ends up investigating himself belongs to the upper echelons even within the lower castes and consequent sub-castes.

Social capital, intersectionality, and empowerment

Intersectionality, therefore, is a crucial tool with which one must attempt to understand the caste ecosystem. ‘One-size-fits-all’ is not a framework that would ensure the empowerment of the minorities and the marginalised. The empowerment ethic must consider the aspects of both strategic (long-term) and practical (immediate) needs, which essentially means, there should be a balance between material growth and socio-cultural and psychological progress.

Even the narrative of social capital is woven around the “commercial castes” in this book, thereby neglecting the most invisible and vulnerable castes in our society. There is a selective inclusion of some castes and a deliberate exclusion of others.

The development model cannot rely on numbers alone. Social capital (networks of relationships built on shared values of trust, faith, knowledge, emotion, and morality), as argued by the author too, is a necessary precondition to the economic well-being of a community. However, even the narrative of social capital is woven around the “commercial castes” in this book, thereby neglecting the most invisible and vulnerable castes in our society. There is a selective inclusion of some castes and a deliberate exclusion of others.

The ‘merit myth’

Another argument that this book presents is how the caste system was never about the privilege of birth but ‘merit’. According to the Cover Story titled, ‘The Merit Myth: An Examination of Casteism in IITs’, published on March 28, 2023, by Watch Out!, the official student media body of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Roorkee, points out that even though the upper caste population is only about 20% on campus, if one looks around, “in campus groups, in student bodies, and in the administration, (one will) hardly find any individuals from the Dalit, Bahujan or Adivasi communities.”

Source: Forward Press

Secondly, the ‘meritocratic’ system has perpetuated forms of discrimination against students belonging to the marginalised social groups, especially, first-generation learners.

A critical understanding and deeper reflection of affirmative action, transformative change, and social justice are required before being quickly judgmental about that one Dalit student who could afford to go to the same school or college as an upper caste student. It does not mean Dalits have the same privilege and are “only pretending to be oppressed so as to benefit from reservations”. Equality is about the redistribution of privilege/power while minimising structural inequities.

Merit as a category is dependent on both economic and cultural resources and therefore cannot be treated as ‘neutral’. Unequal social structures feed into the so-called ‘neutrality’ of merit. As pertinently raised in the article, “It does not take into consideration how the upper castes are transforming their caste capital into modern-day ‘merit’. As the Supreme Court explains, “a ‘meritorious’ candidate is not merely one who is ‘talented’ or ‘successful’ but also one whose appointment fulfils the constitutional goals of uplifting members of the SCs and STs and ensuring a diverse and representative administration”.

Therefore, a critical understanding and deeper reflection of affirmative action, transformative change, and social justice are required before being quickly judgmental about that one Dalit student who could afford to go to the same school or college as an upper caste student. It does not mean Dalits have the same privilege and are “only pretending to be oppressed so as to benefit from reservations”. Equality is about the redistribution of privilege/power while minimising structural inequities.

For a democracy to sustain itself, it is important to recognise and reverse the effects of long-term systemic oppression and suppression that the subordinate castes have faced and struggled with for generations. Reservation, therefore, comes as an act of atonement; “to make up for all the times that their communities were denied basic human decency”.

Reservation and Representation

Reservation is not “charity”, it is an act of acknowledging the injustice that people belonging to an inferior caste have been fighting against (and still are) for years. It is about creating a level-playing field by ensuring social mobility for those who have been questioning their self-worth due to their inferior birth. We also need to examine whether the tool of reservation alone can ensure agency and selfhood to a lower caste individual.

This is exactly what we need to question while looking at the phenomenal statistical representation of caste communities across sectors based on NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) or NFHS (National Family Health Survey) data – what about the agency and decision-making power? Has the numerical growth achieved escalated levels of dignity and self-worth among those who are exploited and discriminated against by virtue of their caste?

During the 13th B.R. Ambedkar Memorial Lecture, while speaking on the fundamental right to equality, Dr Justice DY Chandrachud asked, “…are constitutional and legal mandates sufficient to protect the personhood of an individual belonging to a marginalised group? Marginalisation embodies a principle of graded inequality. It is important to remember that humiliation is an integral part of an inherently dominant society that perpetuates marginalisation (India Today, 2021).”

This is exactly what we need to question while looking at the phenomenal statistical representation of caste communities across sectors based on NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) or NFHS (National Family Health Survey) data – what about the agency and decision-making power? Has the numerical growth achieved escalated levels of dignity and self-worth among those who are exploited and discriminated against by virtue of their caste? Can values of dignity, self-esteem, and self-worth, after all, be measured?

Consciousness-raising, as argued by Paulo Freire, is something that must be embedded in public policy discourses and welfare schemes. Empowerment is a cyclical rather than a linear process, argues Freire. To illustrate this, let us consider what happened earlier this month. According to media reports, a Dalit man and his mother were allegedly assaulted by a group of upper-caste individuals (with Rajput surnames) in Gujarat’s Mota village, Banaskantha district. The victim was questioned on his “choice of clothing and sunglasses” and punished by the accused who expressed their “dissatisfaction with his ‘elevated status’ (Outlook, 2023).”

Here, consciousness plays a pivotal role in ascertaining the attitude of people. Why is it hard to imagine a Dalit man dressed in fashionable clothes? The mindset is such that it is inconceivable and somewhere even discomforting to reconcile to the development and advancement of a community which has been historically, culturally, and sociologically relegated to an existence of invisibility. As members of civil society, it is our collective responsibility to alter such behaviour and be human and humane.

Annihilation of caste

When Vaidyanathan talks about healthy competitiveness and the spirit of caste clusters that can eventually work toward their upward mobility in economic registers, what is not taken into account is the fact that in their struggle to formulate close-knit groups and units, they have not received any support or assistance from the upper caste communities. Additionally, the predominance of these caste clusters is invariably in the non-corporate, unorganised “service” sector – they are meant to ‘serve’.

Abolishing caste, writes Vaidyanathan, “is to homogenise Indian society”, and reformers and activists have not really succeeded in doing so. True, heterogeneity and diversity lend character to a democratic India but the question remains, are we, as a society ready to embrace and practice (as a moral duty) tolerance, harmonious co-existence, inclusion, and empathy so that we can be leaders in the path to achieving sustainable and substantive equality?

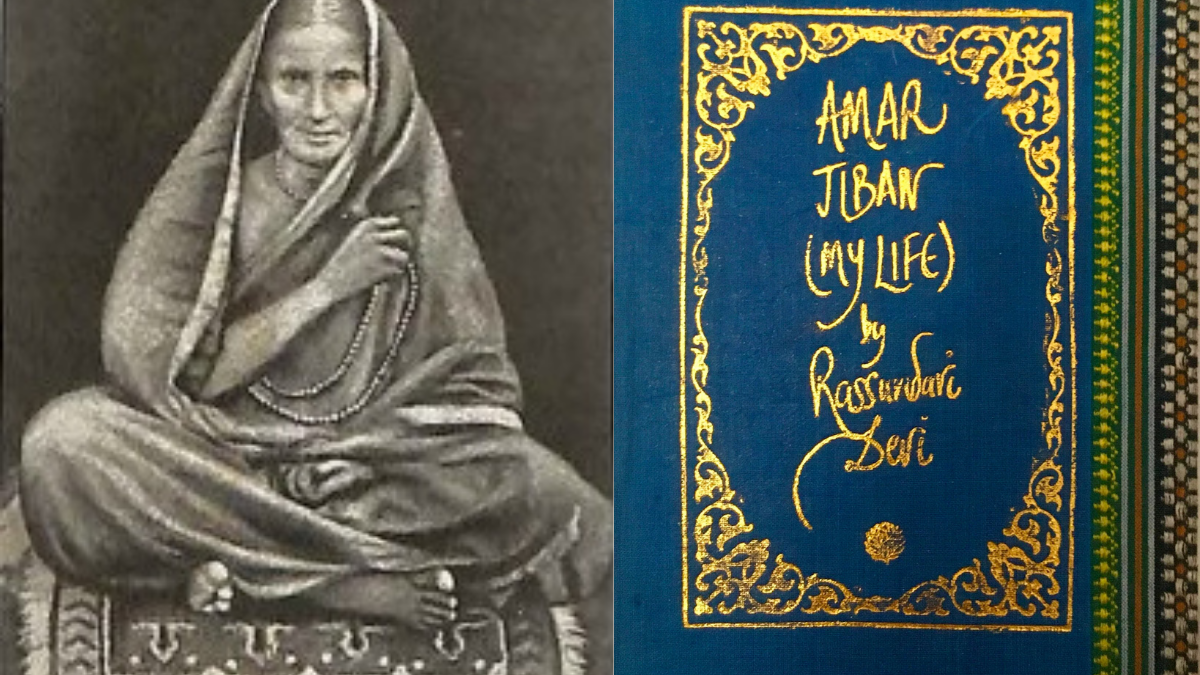

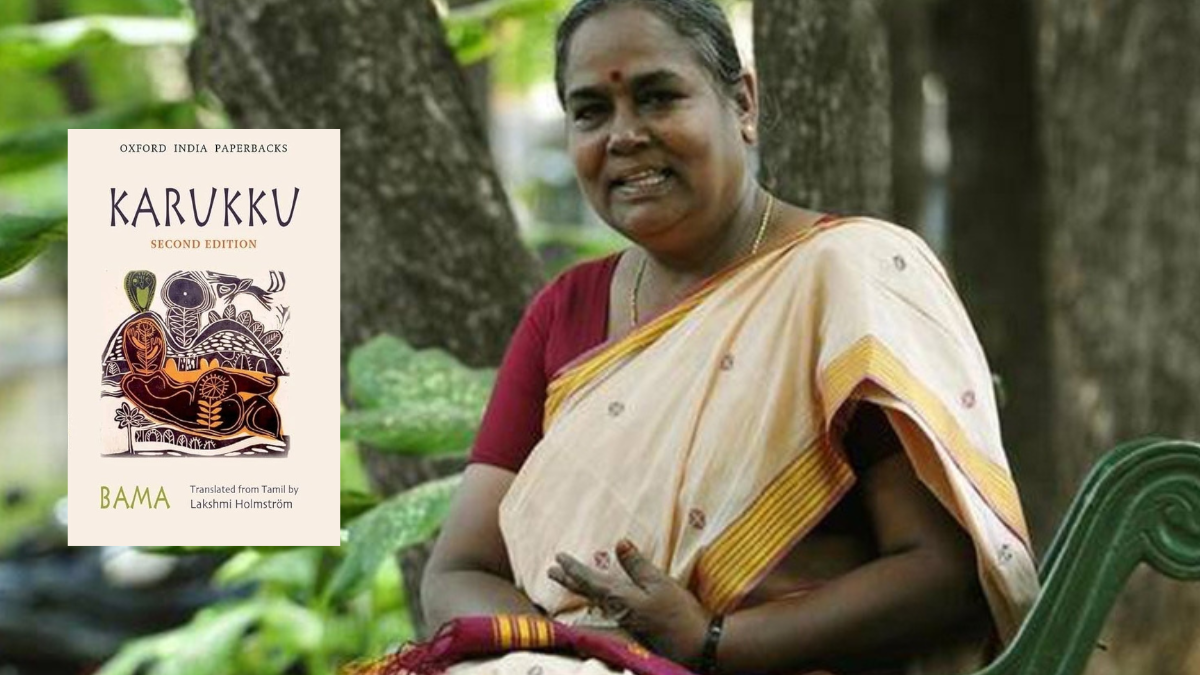

Since the book presents a “qualitative view of caste”, it would have been more enriching and authentic if the author had included personal narratives and stories of people from the plumbing, cleaning, and domestic/household segments of the society since that would have given the reader a glimpse into the lived realities (situated subjectivity) of lower-caste workers and what they feel about their social standing.

In the concluding chapter, the author discusses the disastrous effects of the “Anglo-Saxon model of atomizing every individual to a single element in a rights-based system…where families have been destroyed and communities have been forgotten”, and argues for a need to have a “duty-based system” over a rights-based one.

Abolishing caste, writes Vaidyanathan, “is to homogenise Indian society”, and reformers and activists have not really succeeded in doing so. True, heterogeneity and diversity lend character to a democratic India but the question remains, are we, as a society ready to embrace and practice (as a moral duty) tolerance, harmonious co-existence, inclusion, and empathy so that we can be leaders in the path to achieving sustainable and substantive equality?

It is time to think and think harder to realise transformative action.

About the author(s)

With over 10 years’ experience in publishing and journalism, Ipshita Mitra has a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU and holds a PG Diploma in English Journalism from IIMC. She did her MA in Gender and Development Studies and is currently pursuing her PhD in Gender Studies from IGNOU.

She has worked with The Times of India, The Asian Age, The Quint, Om Books International, World Monuments Fund India Association, and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2016, her short story ‘Cacophony of Silence’ was published by Nikkei Voice, a Canadian-Japanese newspaper. In 2020, her short story ‘Bohemian Sailor of the Gulf’ was published by Sublunary Editions, a Seattle-based independent publisher. The Indian Quarterly (April–June 2021) published her short fiction, ‘Kabuliwala Returns’. She writes on books, culture, environment, and gender for TerraGreen, The Hindu, Scroll.in, The Wire, Wasafiri, Firstpost, Huffington Post, India Currents, and others. She tweets @ipshita77.

Caste has been politicised in India to be able to divide and rule. Much maligned Manu divided people into 4 groups based on WHAT THEY DO, but politics, has turned it into how they were born, and against 4 there are 4000 castes They are really ‘professions’ The anachronism is that when a (say). Barber’s son gets education, thanks to reservation and rises to a high post , is he still to get priveleges meant for a barber , or should it go to a practising barber? . To say Caste is a curse of Hinduism is totally untrue, every religion has the same ‘professions’ e.g Muslim barbers want the same privelege as Hindu Barbers.though Islam is claimed to be a brotherhood, where ALL ARE EQUAL Caste – read professions’ are there in every religion, but it is easy to bash the Hindus, due to thousand years of slavery .