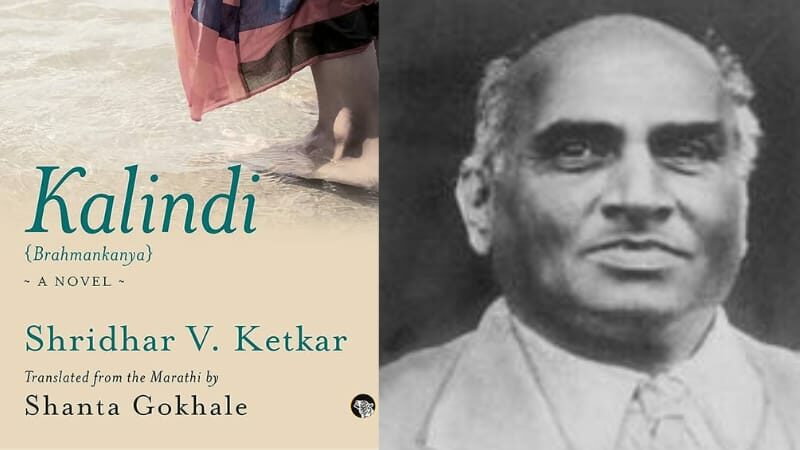

Published in 1930, Shridhar Vyankatesh Ketkar’s Brahmakanya was considered brave and ahead of its time. Translated from the Marathi as Kalindi by Shanta Gokhale, the novel tries to do an ambitious job of imagining a casteless society free from the institution of marriage. Set in the early 20th century, Gokhale’s translation tells the story of an outcast Kalindi’s journey of rebuilding her identity in Mumbai after suffering from losses in Pune.

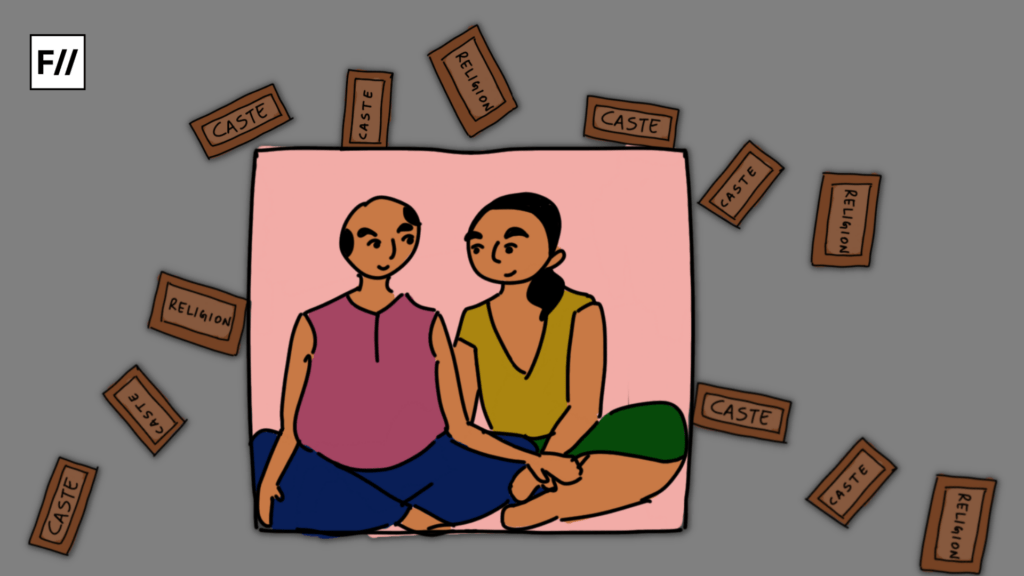

Appasaheb Dagge, a Brahmin, dreamt of a casteless world. He married Shanta, the daughter of a doctor and his mistress. He believed that all the castes could become one in Brahminism. That is to say, Brahminsim could become all-inclusive through intercaste marriage. He believed that it could raise the lower castes to the same level of respect in society. And yet, he couldn’t let go of his caste pride. He expected his wife to behave and socialise in a certain way that stated that she’s a Brahmin. Kalindi and her siblings were born out of this wedlock and were still marginalised in society as outcasts.

Grandmother and granddaughter defy the institution of marriage

Shanta’s mother, Kalindi’s maternal grandmother, is a school teacher. She defied the institution of marriage twice. She was married as a child and with the help of a lawyer she could get out of that wedlock. She was educated. She had an aura of belonging to the upper caste. She chose to be a mistress to a doctor, rather than marry him. Her daughter, Shanta was born out of wedlock and hence, was a bastard.

In the society depicted by Ketkar, bastards, widows, and widowers were the only ones who moved away from the caste system. They were accepting for they were ill-fated enough to have no caste pride. Before her demise, in a letter, she advised Appasaheb and Shanta to look for such people in matrimony for their children. Appasaheb Dagge caught in his caste pride wanted Brahmin partners for his children. He did not want her wife’s past to haunt them. He assumed his children will be devoid of the past and be seen as Brahmins.

Contrary to his ideologies, his elder daughter Kalindi was well aware of her position in the society. She heeded her grandmother’s words and chose love over marriage. She defied the institution just like her grandmother when she dropped out of college and became a mistress to Shivashranappa, the man she loved. He already had a wife. Kalindi felt no desire to marry him. She believed love was greater than marital obligation. She was choosing to be with him, rather than being obligated to do so. Her fate changed when Shivashranappa abandoned her and their son. Kalindi with the help of her friend who belonged to the marginalised community of Bene Israel finds a job in Mumbai. She comes across a trade union leader, Rama Rao. Though a Brahmin, he does not indulge in politics that will help labourers only on paper while exploiting them.

Kalindi and Rama Rao not only share the interest of helping the labour class, but also respect each other’s intelligence and approach to social reform. In their conversations, they develop love and respect for each other which leads to marriage.

Personal happiness taking the sting out of social evil

Kalindi, perhaps having learned the lesson with Shivashrinappa or perhaps finding a better partner in Rama Rao, chooses to marry while not sticking to gender roles. She advocates for a marriage where a woman earns a living and supports her husband as he establishes himself. Patriarchy along with caste is questioned in the novel. Rama Rao is hesitant to marry Kalindi knowing that Shivashranappa may any day return to claim his son that he has abandoned.

Kalindi, perhaps having learned the lesson with Shivashrinappa or perhaps finding a better partner in Rama Rao, chooses to marry while not sticking to gender roles. She advocates for a marriage where a woman earns a living and supports her husband as he establishes himself. Patriarchy along with caste is questioned in the novel.

Kalindi’s brother travels across India to learn about all the social reform movements and organisations that claim to bring about equality and is dissatisfied with them equally. Appasaheb Dagge’s caste pride is challenged by his children who make their life decisions and choose their partners irrespective of their caste and religion. Unlike Appasaheb they do not wish to create social reform in the end but choose to live a happy life with the consequences of their actions.

Everything that the story challenges in the beginning is given a comfortable happy end. The translation states, ‘personal happiness took the sting out of social evil.’ This leads the reader to wonder, would it have been true if the marriages, in the end, did not have a Brahmin man? Could the women, in the end, be happy if the Brahmin men in question had not accepted them?

Everything that the story challenges in the beginning is given a comfortable happy end. The translation states, ‘personal happiness took the sting out of social evil.’ This leads the reader to wonder, would it have been true if the marriages, in the end, did not have a Brahmin man? Could the women, in the end, be happy if the Brahmin men in question had not accepted them.

The story leaves the reader wondering about the next generation of children. If Kalindi resented her father for marrying an outcast, then what fate lies for her son? Born to a mixed-caste mother and Lingayat father, her son is ultimately raised by a Brahmin father. It might have been a revolutionary book in the 1930s as it shows a marginalised woman taking charge of her life. But how far does this revolutionary act go when it ultimately leads to marriage?

Kalindi was ahead of its time, but it does not make a radical statement against patriarchy or the caste system for that matter. It is the love and generosity of Brahmin men that help the women. The only difference is that they did not act with the intention of bringing about a social change as was intended by Appasaheb, they wanted to be with the people they loved. It is as much an act of bravery for them as it was for Appasaheb at the beginning of the story. However, their caste pride did not take over the love and respect they have for their partner.