The description that accompanies the Kohrra on Netflix tells us that the story follows two police officers unravelling the circumstances behind the death of a soon-to-be-married man. Yet another dark, gritty whodunnit with plot twists and morally ambiguous characters abound. Though technically accurate, this one-liner is itself a smokescreen, a kohrra (fog) of sorts fabricated to lure the viewer into a false sense of certainty that comes from their prejudices of what a murder mystery is supposed to be. Kohrra successfully manages to transcend the genre of the crime thriller while going through the same beats.

A dead body found under suspicious circumstances, a mother desperate for answers, a daughter suffocating under her father’s tyrannical hold – a traditionalist father who expects his son to ‘man‘ up. None of these circumstances are particularly novel; what elevates them to become more than the sum of their parts are the specificity of the writing and the sheer brilliance of the performances.

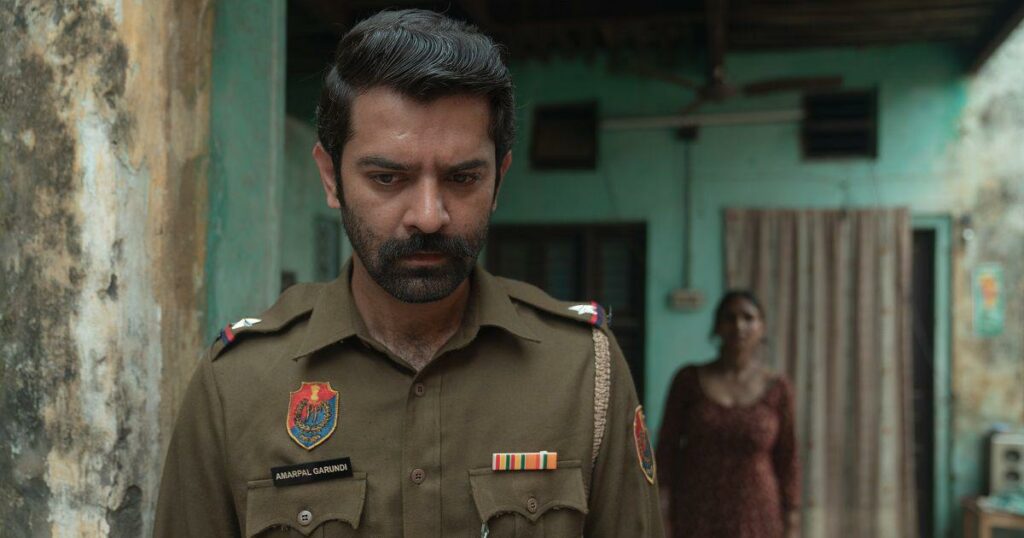

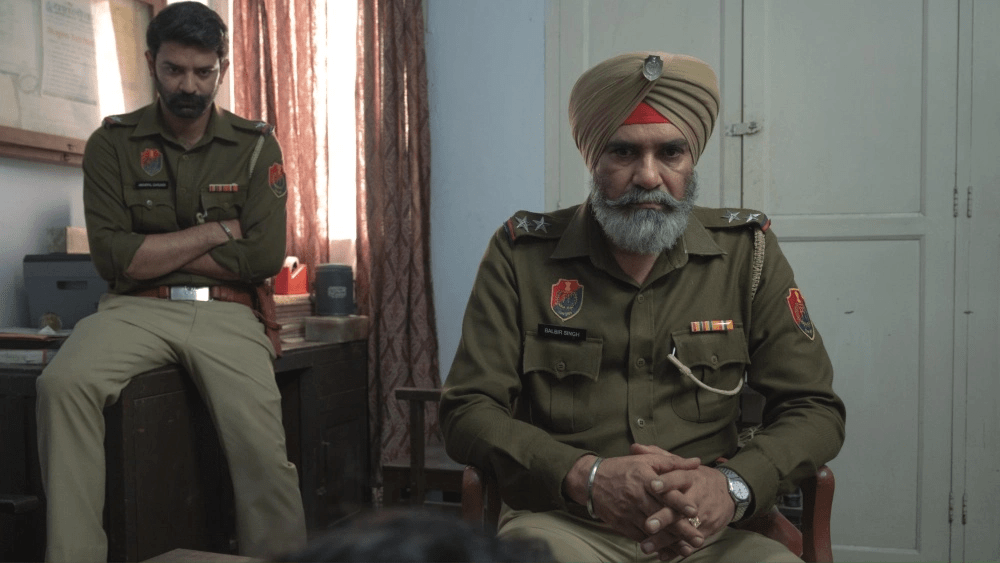

As the mystery unravels around Sub-Inspector Balbir Singh (Suvinder Vicky) and his deputy Amarpal Garundi (Barun Sobti), we are plunged headfirst into the murky depths of small-town life in Punjab.

The plot follows a police investigation of the mysterious death of Paul Dhillon, an NRI from England who has landed up in Punjab’s Jagrana for his arranged marriage to Veera Soni (Aanand Priya). Adding to the drama, his English friend Liam Murphy (Ivantiy Novak) who had tagged along for the wedding is nowhere to be found.

What is apparent right from the very first episode is the attention to detail that has gone into every frame of the show. Everything from the cadence of the police officers’ cussing to the lingering echoes of prisoners being tortured in their cells is intentional. In the first episode, we follow Balbir and Garundi as they enter Paul’s bedroom inside his family home.

The camera strategically lingers on seven pairs of shoes of all brands and colours, tidily arranged inside his closet. We are never told that Paul comes from money, but it doesn’t matter because a quick glance at their wallpapered foyer and the airy sitting room is more than enough.

Later in the Kohrra, we meet Kulli, a drug addict living in a decrepit, claustrophobic room and his long-suffering mother, unsurprised when a Sub-Inspector knocks on her door to talk to him. Though we are not explicitly made aware of their dynamic, we feel her weariness through the screen as she says: ‘Well if the police want my son, then it can’t be a good thing.’ All in all, the series cuts across social class and financial status to give us an incisive peep into modern-day Punjab.

Dysfunction that cuts across social class

The protagonist of the show and the leading investigator, Balbir Singh’s calm professional front is contrasted with his dysfunctional personal life. His daughter Nimrat (Harleen Sethi) is recently separated from her husband Raman and so back to living under her father’s roof, this time with her son Golu in tow. In Nimrat’s introduction scene we see her discussing her impending divorce with a lawyer who asks why she wants a divorce in the first place— was he physically or mentally abusive? Was he not sexually competent?

This is exactly what perplexes Balbir for the greater part of the show — here is a man who cares for and looks after his wife and son, so what does he lack? It does not even occur to him that Nimrat may just not want to be married, that she just does not see herself as a mother. Balbir flat-out denies her the right to make her own choices, whether that may be in her love life or her career, coercing her time and again to conform to what he thinks a woman should be like.

Through flashbacks and dialogues, we are shown glimpses of the life Balbir shared with his own wife. It is implied that she suffered from a mental illness for which Balbir would force her to medicate herself. She runs from room to room, throwing pots and pans at her husband, voicing her dissent at the top of her voice. She asks him desperately over and over again ‘Why don’t you understand?‘ to which he responds with a sharp slap across her cheek, as young Nimrat listens quietly from the porch. Nor could Balbir understand his wife in the past, nor can he understand his daughter in the present?

In another flashback, we are taken to the Dhillons’ life in London, just a few years ago. Satwinder Dhillon moved to London when his son Tejinder was just a boy. Soon Satwinder is rechristened ‘Steve,’ just as his son becomes ‘Paul.’ The flashback takes place when Paul, a teenager at the time, has cut his hair short in an effort to fit in with his English classmates and is hidden out at his friend Liam’s house.

Steve flies off the handle, whipping his son’s body over and over again with a belt until his wife throws himself over Paul. When Clara Murphy (Rachel Shelley) threatens to call the police, Steve screams out loud that Paul is his son; he will always be Steve Dhillon’s son first and his own person second. This of course foreshadows the great reveal at the end of the show that Paul was in love with Liam and agreed to the arranged marriage only out of fear for his father.

These two central parent-child relationships mirror each other. Though the two may seem miles apart because of the obvious separation in their social and financial classes, both Steve and Balbir are two sides of the same coin. Both of them are traditionalist Patriarchs who believe that their children should fit into the mould of the ‘good,’ Punjabi son or daughter. Balbir, though fortunately learns from Steve’s story; he comes to understand the consequences of not letting his daughter be her own person. And so the series ends with Balbir patiently listening to his daughter for once, lending Nimrat the same understanding that her mother had once asked for.

Crime, class and Kohrra

From the very first episode, the show stands firm in its decision to humanise all of its characters. Whether it be the perpetrators of the crime or the khaki-clad police officers, nobody is perfectly good or evil. The investigation becomes but a medium that enables us to look at contemporary Punjab in all of its terrifying glory. The police inquiry takes us on a journey that transcends social class and rural-urban divides.

Despite being one of the prime suspects in the investigation, Happy Dhillon (Amarinder Pal Singh) is let out of police custody only because of the connections his father has with the law enforcement higher-ups. Balbir and Garundi are asked not to follow up on this lead, never to disclose Happy’s possible involvement in the murder at all. On the other hand, people like Kulli or Saakar, suspects who are just as likely to have had a hand in Paul’s death but alas do not have the good fortune of well-connected fathers, are locked up and tortured mercilessly with nobody to speak for them.

Kulli is hospitalised and in dire need of medication when Garundi disregards the doctor’s orders and brings him into custody anyway. Predictably his condition worsens while he is alternatively beaten up and left unattended. When Balbir throws an accusatory glance his way, Garundi is peevish but not yet remorseful. After all, why should he be? In the grand scheme of things, Kulli is no more than a pawn to be sacrificed for the greater good of the rich and the powerful.

In several scenes of the Kohhra, his senior officers repeatedly ask Balbir to focus on Liam’s disappearance rather than Paul’s murder. A missing white man will be more cause for hand wringing compared to a dead brown man, even though they are both British citizens. Though perturbed, Balbir is in no position to comment on the injustice of the system, not only because his job is on the line but because he too has partaken in the perks that the system has to offer. He too has made calls asking a minister for a favour and he too has branded an innocent man a traitor so that his culpability in another crime is not revealed.

In the end, the show leaves you with the question, is there any real difference between the investigating officers and the ones they call criminals?

About the author(s)

Keerthana (she/her) is a third-year English Literature student at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University. She is interested in analysing art and pop culture through feminist and other sociocultural theories. She enjoys literature, music, films and the occasional cricket match.