Every Indian at heart gushes with pride and honor as the nation commemorates the 77th year of its Independence and liberation from colonial rule. Integrating a diverse nation, intricately yet strongly, the Indian Constitution is among the greatest success stories that the nation has. Our nation, a Sovereign, Socialist, Secular and Democratic Republic with a federal constitution, ensures interest of minorities in supreme aspect. Article 29 of the Indian constitution protects the interest of minorities, by providing a provision that any citizen or section of citizens having distinct language, caste, script or culture have the right to conserve the same.

It mandates that no discrimination would be done on the grounds of religion, race, caste or language. Similarly, the Right to Equality, Articles 14 to 18 enshrined by the Indian Constitution, protects the interest of minorities by providing them equality in all domains like, Natural, Social, Civil, Political, Economic and Legal by prohibiting discrimination, abolishing titles and untouchability, therefore providing equal opportunity in matters of public employment and access to public spaces like, educational institutions, hospitals etc. But while the supreme law of India is promising and tends to ensure an unbiased society for its nationals, the current circumstances are contradictory and antithetical.

The irony of ‘Amrit Kal‘

‘Amrit Kal’ is a phrase that can be read everywhere, on hoardings, headlines etc., signifying ‘elixir of inspiration from liberation fighter’. Indeed we are in an era of our Independence where we must be content for what we have today, and what better could be made for tomorrow. We show gratitude towards the million lives, who took a stand and fought for a better tomorrow of their nation and the generations to come. But, is this liberation shared and equal, like it was originally supposed to be?

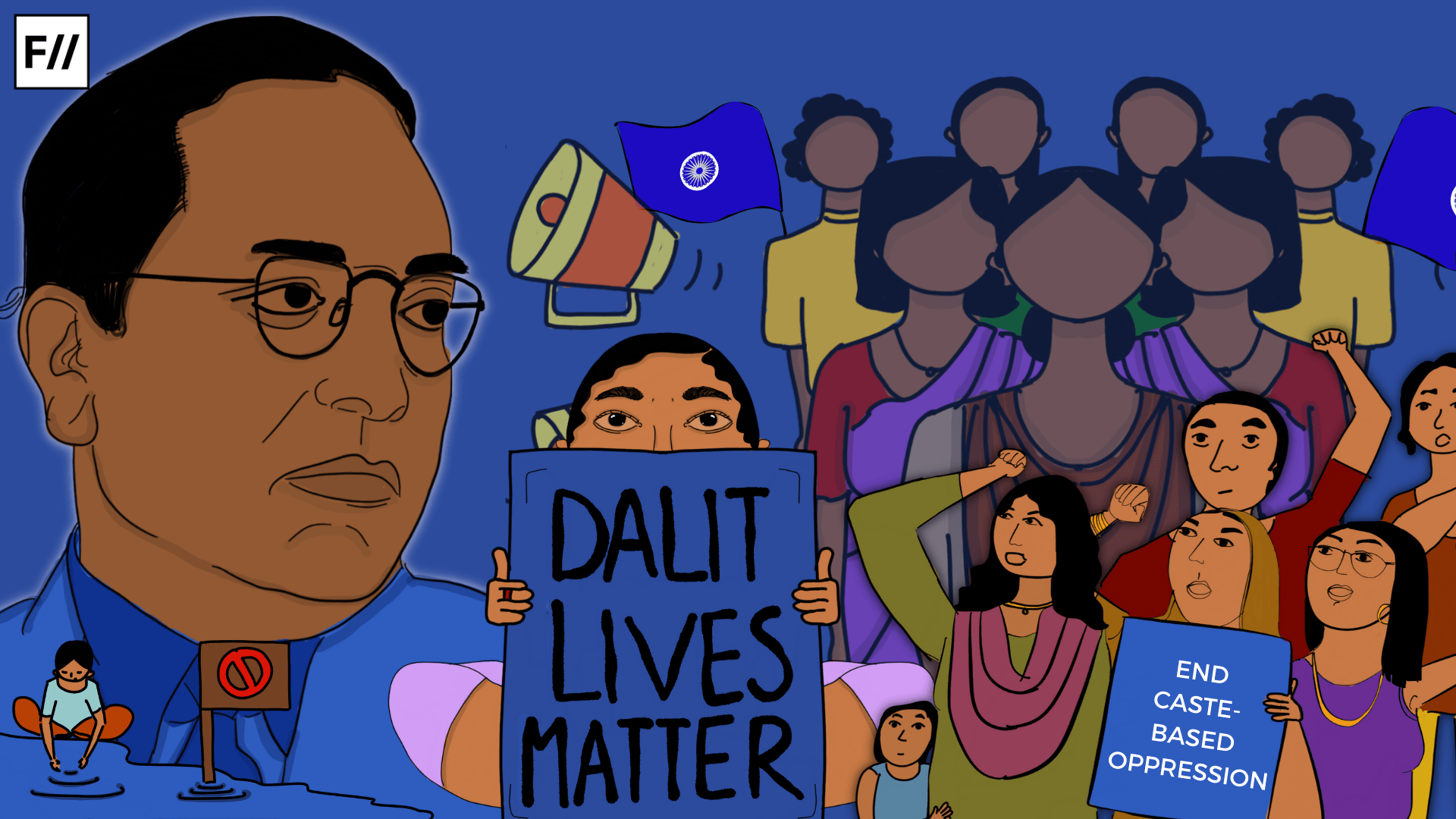

In its youthful 77th year of Independence, half of India’s population is still suffering for its share of liberty, equality and recognition. They are seeking liberty from the age old bane of caste system which is still standing strong in the country. The defiance of rights by the higher educational institutions reflects the bleakness of the same. Caste discrimination is a harsh reality in these academic institutions. The recent increase of suicides among Dalit and other minorities’ students are testament to it.

Campus experiences and caste

On campus divide and discrimination amongst the students have become more steep and wide. ‘Education is very often the only way of upward social mobility for marginalised students of lower castes, and poor treatment at these very mediums of upliftment sets them back’ narrates Dr. N Sukumar in his book Caste Discrimination and Exclusion in Indian Universities: A Critical Reflection.

Citing his research Dr. Sukumar further notes, ‘What is important to note here is that the marginalised students from rural areas are deeply committed to the transformation wrought by higher education. Metropolitan students who don’t succeed simply find another job, start a business, or recuperate and start again somewhere else. For these marginalised students, this opportunity [to study] is the only one. Such a condition when these students are denied the only way of upliftment can also lead to suicides’.

Caste discrimination in academia

Last year at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), one of the most sought after central institutes for higher institutes, a faculty member was condemned for allegedly giving lower marks to Dalit Ph.D students causing them to fail. Another incident is of Darshan Solanki, a B.Tech student at IIT Bomabay, who ended his life, succumbing to casteist hatred. This rabid casteism also took the lives of Dr. Preethi, a Scheduled Tribe student form Hyderabad and a Schedule Caste MBBS student Pamposh.

There are plenty of such cases that remain unacknowledged because of ineffectuality of these sections in the society. In the case of Dr. Preethi, the narrative reflected into ragging being a prime cause for her death. What is more terrifying and disturbing, is the connection and active engagement of students in the casteist bullying. These students have submitted into the evil tradition of caste segregation, inspired of studying in higher educational institutes.

Is India’s youth truly “educated”?

Universities like the IITs, were founded as institutes of national eminence. They were granted outsised funding as a necessary financial cost to educate excellent engineers. Admission to elite places like the IITs and every other prominent higher educational institute requires students to overcome steep structural barriers and filters. But inspite of their stellar education, these students remain unempathetic to the victims of systemic oppression.

After having overcome the structural barrier of financial strains, caste etc. the minority students are stigmatised and labelled as ‘quota students’, and are often accused for stealing the seats of truly “deserving” upper caste students. The minority students are cast into the darkness of inferiority and inappropriate success.

After having overcome the structural barrier of financial strains, caste etc. the minority students are stigmatised and labelled as ‘quota students’, and are often accused for stealing the seats of truly “deserving” upper caste students

Consider the case of Vaibhav Jadhav a former student at IIT Madras. On February 16th, 2023, Vaibhav took to twitter, mentioning how he was cornered by group of seniors during his freshman years, ‘Seeing that I was not one to fall in line, one of them asked me my rank,‘ wrote Jadhav. ‘I gave my SC (scheduled caste) category rank, to which he replied “Sala SC hone ke baad bhi itna attitude dikhata hai! (Showing so much attitude despite being an SC)’ writes Jadhav. He further said how this continued throughout his five years at the institute.

61 students took to ending their lives at the IITs, NITs and IIMs between 2018 and March 2023, succumbing to various factors like, academic stress, family reasons, mental health issues and more, according to a data presented by the Ministry of Education in the Rajya Sabha on 15th March this year. Foreseeably 55% of them were from marginalised communities.

Covert casteism in academia

Casteist slurs in the educational spaces are thrown at the students by the supervisors too. For instance, a former PhD student at JNU belonging to a minority community (choses to be anonymous) while talking to a magazine recounted how he was prohibited from presenting his research proposal during the viva, and was instead told that he should have attended Jamia Milia Islamia, ‘because I am a Muslim’. The 28 year old said, ‘After telling me that my thinking was highly colonial, he forbade me from explaining my research, he was rude’.

Amid these data and statistics what still remain unaccounted is the mental strain that these students go through. Such stratification, cast noxious effect on academic performance too, and might also hamper an individual for lifetime.

Amid these data and statistics what still remain unaccounted is the mental strain that these students go through. Such stratification, cast noxious effect on academic performance too, and might also hamper an individual for lifetime.

The question that arises here is what exactly the powers of the state are doing, apart from counting the numbers of such dismal incidents. The alarming numbers and the nerve racking incidents faced by the minority communities in these public spheres begs interventions from the authorities concerned.

About the author(s)

Anupama intends to be an artist in neutral, aka a dabbler- cum-learner. Her interests lie in music, nature, stories transcending cultural boundaries, human welfare, etc. When she is not around she can be found strolling along the ghats of Varanasi. To add she has a lab- named Miley.