By Sameer Ahmad

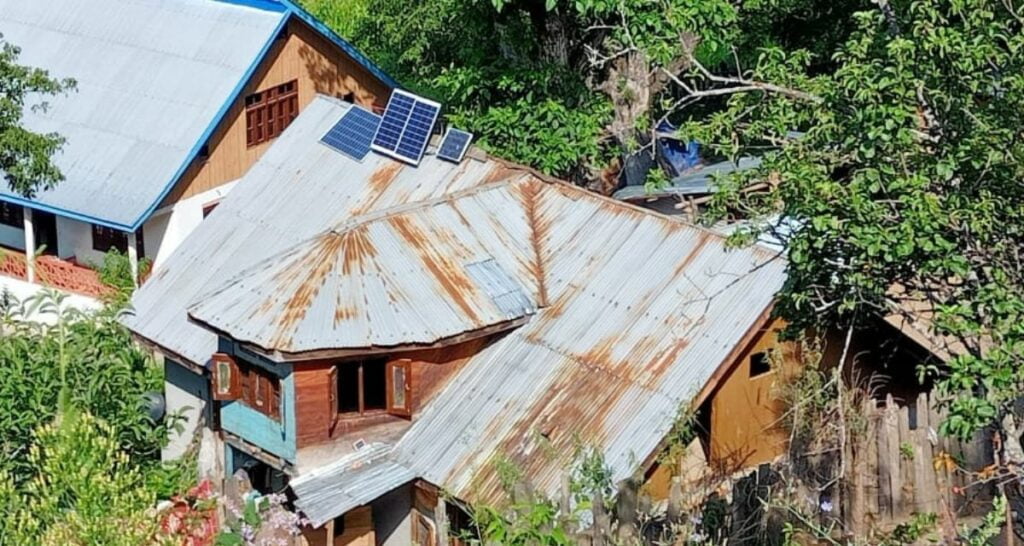

‘Warwan Valley is exceptionally stunning – even for Kashmir…The valley’s remoteness and isolation compound this beauty. This is a side of Kashmir that even most Kashmiris haven’t seen.’ This is how a trekking company describes Warwan Valley, nestled in the Pir Panjal mountains between Ladakh and Kashmir. ‘Villagers on horses are common, almost like how people use scooters in the cities. After a while, it isn’t surprising to find horsemen galloping towards a village raising a cloud of dust behind them! Almost like an incredulous scene from a movie,’ it says.

The residents of Warwan, however, do not share tourists’ romanticised notions of remoteness and isolation. ‘It feels like we are still living in the 90s. We are forced to walk miles as there is not a single bus service to our region,’ Azad Nabi Lone (37), the Sarpanch of Brayan village in Warwan Tehsil told 101Reporters.

Warwan, a picturesque valley in the Kishtwar district of Jammu and Kashmir, has a population of more than 60,000 people, which has almost doubled since the census in 2011 when 35,572 people were residing in 55 villages. In 2014, the valley — with its three blocks of Marwah, Warwan and Dachhan — was made a Sub-Division with its headquarters at Marwah. In October 2022, the region garnered attention when Farooq Abdullah, president of the political party National Conference, rode a horse to visit Marwah.

The main occupation of Warwan Valley is farming. People grow wheat, paddy, maize and kidney beans besides collecting herbs from the forest to sell. Marwah Rajmah is famous for being grown at high altitudes and free of fertilizers. ‘We procure about 200 tonnes of rajmah from Marwa every year and sell it at the rate of Rs 160 per kg,’ said Gh Mohammad Ganie, a merchant in Anantnag.

Few people are into government jobs. Many also travel to Chenab and Kashmir Valley for seasonal labour work and return home in winter. Located at an altitude of 2,134 metres, Warwan is cut off from the rest of the state due to heavy rainfall for seven months a year. ‘People have to stock up grain and essentials for winters as there is no connectivity apart from helicopters then,’ said Mohammad Hussain (40), a resident of Marwah.

Marwah is 200 km north of Kishtwar, the district headquarters but no direct road exists between the two places. The only road that connects the residents of Warwan to the rest of the state is from Marwah to Anantnag in the West, a distance of 120 km. No state transport service works on that.

For a Warwan resident to travel to his district headquarters is an uphill task. They board a shared private vehicle, usually a Tata Sumo at the rate of Rs 600 to Anantnag and then another vehicle for Rs 350 from there to Kishtwar, a circuitous route. ‘It gets evening by the time we reach Kishtwar and no work gets done as all offices start shutting down by then. The Sumo fares also depend on the weather. If the weather is bad, the driver will increase the fare. Imagine, in this day and age we still haven’t seen a bus in our village,’ said Rouf Lone (33) a resident of Marwah block.

Education, health out of reach in Warwan

Students and patients particularly face the brunt. Amir Bhatt (17), a standard 11 student from Gumree village has to walk seven km to the government high school in Aftee village every day. ‘Sometimes we leave home on an empty stomach as there is no time to eat. We have to leave early and reach home quite late. It is exhausting and even leads to disinterest in studies. When it snows, we have to stop going to school completely,’ said Bhatt.

Danish Ahmad Rather (25) also from Gumree, had to abandon further studies after standard 12 due to lack of transport and poverty. ‘There is only one degree college in Marwah, about 30 km from our village. It functions out of a rented building, has only one permanent lecturer and only offers Arts courses. Students wanting to study further in other streams have to go either to Anantnag or Kishtwar. Not everybody can afford to stay away from home, so we are forced to drop out. If there was a proper bus, we would not have to give up our education,’ said Rather.

The Marwah Community Health Centre does not have adequate facilities, claim residents. ‘No specialised treatment is available here. We have to rush a person to Anantnag or Srinagar, the state capital, in case of serious issues, but only if there is a vehicle. Last year, Mohammad Amin (53) in our village complained of fever and chest pain in the evening. He was rushed to Anantnag but he died on the way. This is a routine affair here, thanks to the state of public transport and roads,’ said Rather.

To avoid last-minute exigencies, pregnant women are shifted to the cities a month before child delivery. ‘There, they stay with relatives or in rented accommodation. Since there is no maternity and child care facility in the sub-division and no transport facility to reach there on time, this is a necessity,’ said Sarpanch Lone. Not just roads and transport, electricity, internet connectivity, health care and education are also the problems plaguing Warwan.

The condition of internal roads is also no good, claim residents. ‘Only a few roads have been macadamized since they were constructed but in Warwan and Dachhan blocks, most roads are still in a dilapidated condition,’ said Rouf Lone.

Frustrated with all this, people are choosing to migrate out of the valley. In Yourdu village, 30 out of 130 families have left the village, informed Lone. 10 years ago, Mehra Begam (60) with eight members of her family, made her permanent move to Anantnag.

‘Walking miles for every little thing was not easy. Once we shifted and my children started work, we bought a house in Wanihama village in Anantnag district only,’ Mehra told 101Reporters. In 2016, Margi, a village of Warwan tehsil was reduced to ashes in an accidental fire. ‘There was no fire brigade or emergency service at the Sub-division and nothing could reach from outside,’ recalled Mehra.

The much-awaited road and the dream of a bus

The roundabout way to reach Kishtwar could be avoided if a road from Marwah to Dachhen existed. That would reduce the distance between the sub-division and the district headquarters to 85 km. Since the road has to be carved through a mountainous forest, work is currently underway along the stretch, informed Dr Devansh Yadav, the Deputy Commissioner of Kishtwar district.

‘We are in talks with the State Roads Transport Corporation and soon there should be a bus at least during summer. In winter, since the area is cut off, we run a helicopter service at 80 per cent subsidy for locals,‘ Yadav told 101Reporters. A chopper trip costs Rs 1,500 from Kishtwar to Marwah (Rs 2,700 without the subsidy).

Dr Yadav said that under the “Mumkin,” scheme of Mission Youth, an initiative of the J&K Government, they have also supported 100 unemployed youth in the district to buy vehicles for ferrying people. ‘Most of these vehicles have been running for a year now,’ said Yadav. People, however, have no idea about the scheme. ‘We have only seen a few commercial vehicles plying on interior roads, nothing else,’ said Rouf Lone.

Sameer Ahmad is a Jammu and Kashmir-based freelance journalist and a member of 101Reporters, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

About the author(s)

101Reporters is a pan-India network of grassroots reporters that brings out unheard stories from the hinterland.